WORDS FROM THE VOICELESS

The Goat Thief is an important addition to the global bookshelf. In this Tamil short story collection by a writer I admire, I cringed often. He tells searing stories of the marginalized.

A few months ago, I read a Japanese collection titled Things Remembered And Things Forgotten by Kyoko Nakajima and at the time I wrote about how I felt that the collection suffered from the inconsistencies of many short story collections.

Mango lovers will know the feeling. Not all the mangoes we receive in a summer basket are equally sweet. Similarly, in The Goat Thief collection, too, a few of the stories did not seem ripe enough to be consumed.That being said, other stories in the collection were so polished and gut-wrenching that I could barely swallow a line I was reading for fear of what else the writer had in store for me.

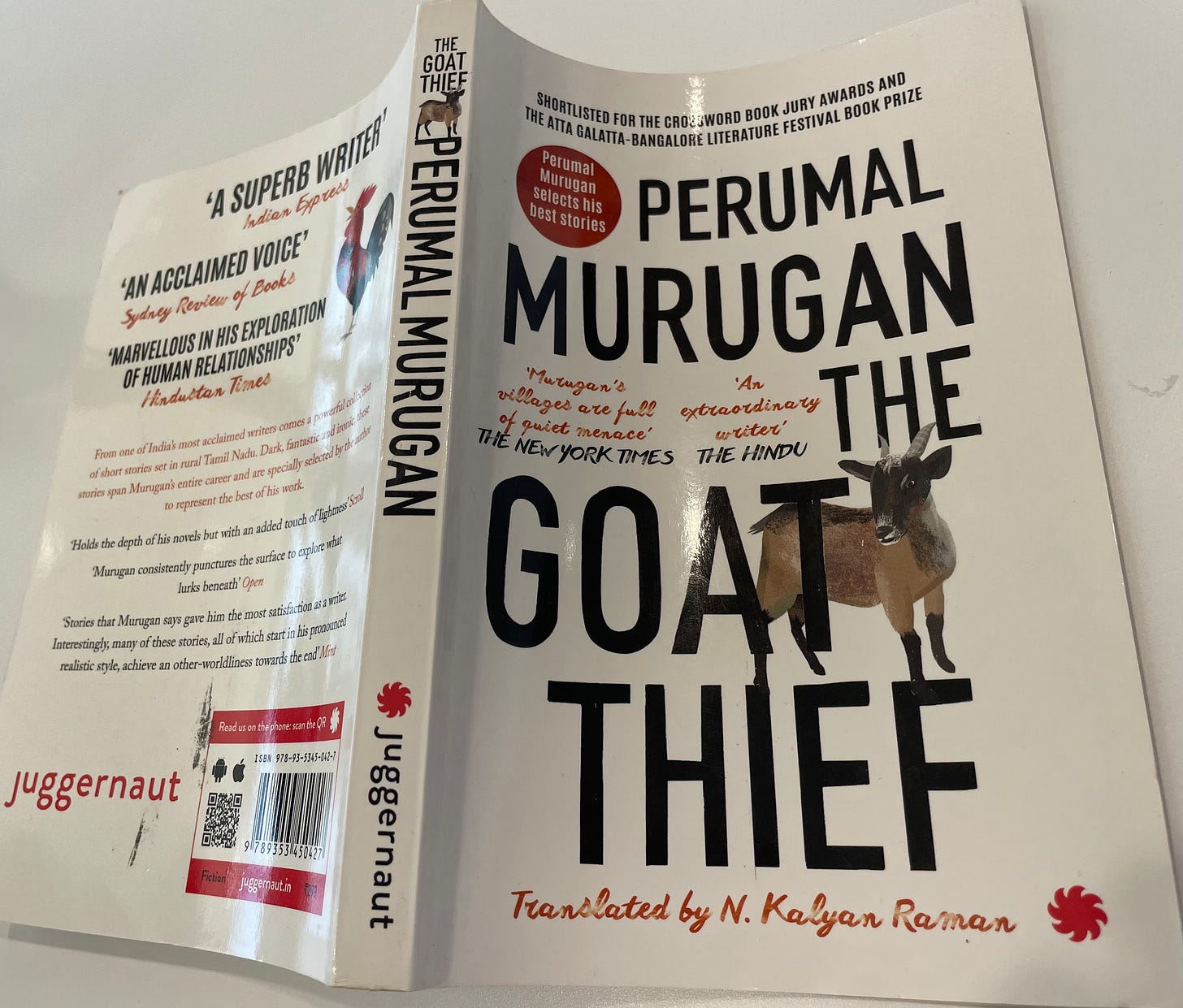

In February, I wrote about Perumal Murugan’s Poonachi and I was thrilled when I met N. Kalyan Raman, the translator in January in Chennai. He gifted me The Goat Thief as well as his translation of C. S. Chellappa’s Vaadivasal, a book I wrote about a few weeks ago. I’m so thankful for this exposure to the world of Tamil literature from a gentleman who has translated several other well-known contemporary Tamil writers, including Ashokamitran, Devibharati, Poomani, Vaasanthi and Salma. Of these writers, Perumal Murugan shot to international fame a few years ago and I wrote about the circumstances of that in my post on Perumal Murugan’s Pyre.

In the title story of The Goat Thief story collection, Murugan narrates yet another of his unforgettable stories about goats. The eponymous story is spine-chilling, with several comical moments. A young man named Boopathy is a skilled goat thief, having learned how to steal with impunity under the able guidance of his father. One day, however, Boopathy’s luck runs out.

A minor slip occurred in Boopathy’s plan. To silence the goat, his fingers clamped its tongue without getting caught in its teeth, but his grip slipped a bit. Adjusting his grip, he tried to choke its vocal coards. In the meantime, the goat opened its mouth with its quaking tongue and raised a lone bleat.

Boopathy is about to place the goat on his shoulders and break into a run to reach the vehicle waiting for him a few yards away when several villagers begin chasing him. The slimy goat thief drops the goat, runs for his life, jumps into a gutter and then curls up behind a wall of sedge grass, waiting for nightfall even as the villagers stay awake looking for him. Though they’re afraid of jumping in after him, they’re hell-bent on smoking him out.

“Dei, none of you can pluck even a pubic hair of mine. Come here, da, if any of you has the guts.” As he became conscious of his mouth muttering the challenge, Boopathy chuckled to himself.

Shit (yes, that’s the title and the author informs us in his preface that it was part of a collection called Shit Stories) was yet another of those stories that sucked me in. A group of lazy young men live in a residence in which a pipe leading from the toilet to the septic tank has burst. They’re oblivious to what has happened until the day a stench begins to decimate their peace. A worker arrives home to fix the problem and the young men watch him jump into a tank of their excrement. (It is horrifying but completely credible for those of us who have lived in India.) What’s brilliant about this story is the symbolism of a plastic cup. The object that is coveted by all these young men in the opening of the story acquires so much significance by the time the story rolls to its fetid end.

He climbed out of the septic tank. We closed our eyes and turned our faces away. The shit that streamed out when the mud block in the pipe had given way was smeared in lumpy bits all over his face. Even in that condition, he bared his teeth and grinned at us. It was like a pile of shit opening its mouth wide. It gave us the creeps.

One of the stories is titled Musical Chairs. It sparkled with resonance for me. It is about a husband and wife who are so in love with each other that the arrival of a chair in their home is a chance for them both to rejoice in their love—for each other and for the chair. They take turns to sit on it and enjoy its comfort until, one day, the wife realizes that the husband won’t ever give her the chance to stay seated on it after he returns home from work.

Little by little, it dawns on her that he thinks of the chair as his possession. Things soon change between them. She whines and compels him to get another one just like it to resolve their dilemma of who will occupy that chair, when, in time, that second chair, too, becomes off-limits to her. He brings home a friend and between the two of them, the husband and his friend monopolize the chair until one day she drags the chair away in a fit of rage. The husband and his friend simply continue to entertain each other while seated on the floor. Once again, the wife is mired in hurt and rancor. Again, she’s all alone.

While reading it I was forced to mull over the idea of space in my marriage. When my husband travels, I look for the chance to revel in my aloneness for a few days, until one day, I cannot take it anymore. Sure, I need the alone time. But how much of it do I need? When my husband returns, and I pick him up from the airport, once the genuine initial exchanges of love are done, we are back to carping about something entirely inane and inconsequential.

We watch the unraveling of a marriage, of the ways in which love leaks out even as resentment seeps in.Marriage is like bone china with a gold trim; the porcelain may be strong and chip resistant but we have to be watchful of all the minor things that can smother the peace of a given day. That’s the artfully delivered message in Musical Chairs.

Loneliness and rejection form the theme of many of the stories in Murugan’s collection. In An Unexpected Visitor, the grandmother who never seems to die is given a tall order, that she must care for her hyper-active great grandson. She must also keep up with his adventures. Soon, she is so busy in the kitchen that she has no time to lie quietly in her porch. She loves the feeling of being needed, of being able to care for the child even when she feels she cannot physically cope with his boundless energy. This is a heartwarming story on what children bring into our lives. While I really enjoyed reading it, I felt that it petered out in the end. It felt incomplete.

In some other tales, too, I felt that not enough had been expressed about the characters’ inner lives or their background. The opening tale, The Well, shows an uncle trying to please his nieces and nephews until they turn into demonic brats who just want to win. Its horrifying end made me wonder why at all he felt so insecure and unloved that he wanted to show off his prowess to his rambunctious nieces and nephews.

I found another story, The Wailing Of a Toilet Bowl, somewhat incomprehensible. A newly married woman is clearly afraid of her new circumstances; she’s in a new town, in an apartment building where people are unfriendly and the only human she knows is her husband who isn’t sensitive enough to her fears. By the time the narrative ends, we see that this woman is hallucinating and catatonic. The last few paragraphs didn’t tie up the story nicely enough.

As the author says in his preface, the short story form is a '“highly challenging form of literature.” While a short story well told is infinitely beautiful, they are daunting even for the most experienced writer. Speaking of the challenges, Murugan references, so thoughtfully too, a daily artistic expression, drawn in rice flour, that’s ubiquitous in Tamil culture.

I am reminded of the art of drawing kolams practiced in Tamil homes. The aim is to draw—in the early hours of morning in the shadowy predawn light—a beautiful kolam at the entrance to your house.

I’d like to use Murugan’s own insightful reference to the kolam to state how I felt about some of the weaker stories in this collection. The dots were there but the artist had simply not connected them all to finish the picture. When everything is squared away, a viewer can sense that too right away.

Among the short story collections I’ve read for this weekly project over the last eighteen months, two stand out. The Greatest Bengali Stories Ever Told curated and translated by Arunava Sinha and With An Unopened Umbrella In The Pouring Rain authored by the late Ludovic Bruckstein, translated from the Romanian by Alistair Ian Blyth. Each of the stories in these collections made me want to shout out their moments of transcendence from the rooftops. I wanted to read them out loud to fellow passengers waiting alongside me at airport gates.

In my view, The Goat Thief—which has received much international acclaim—does not quite make it to that list for the reasons I mentioned. Having said that, I must also add that almost no collection I’ve read thus far tells the story, bravely and unstintingly, of the people who will always remain on the fringes of society, unseen, censured, and derided. This collection is an absolute must-read, especially for those of us fortunate enough to be wallowing in our own snot and pee, mired in what are first world problems.