SINGED BY THE HEAT OF A BOOK

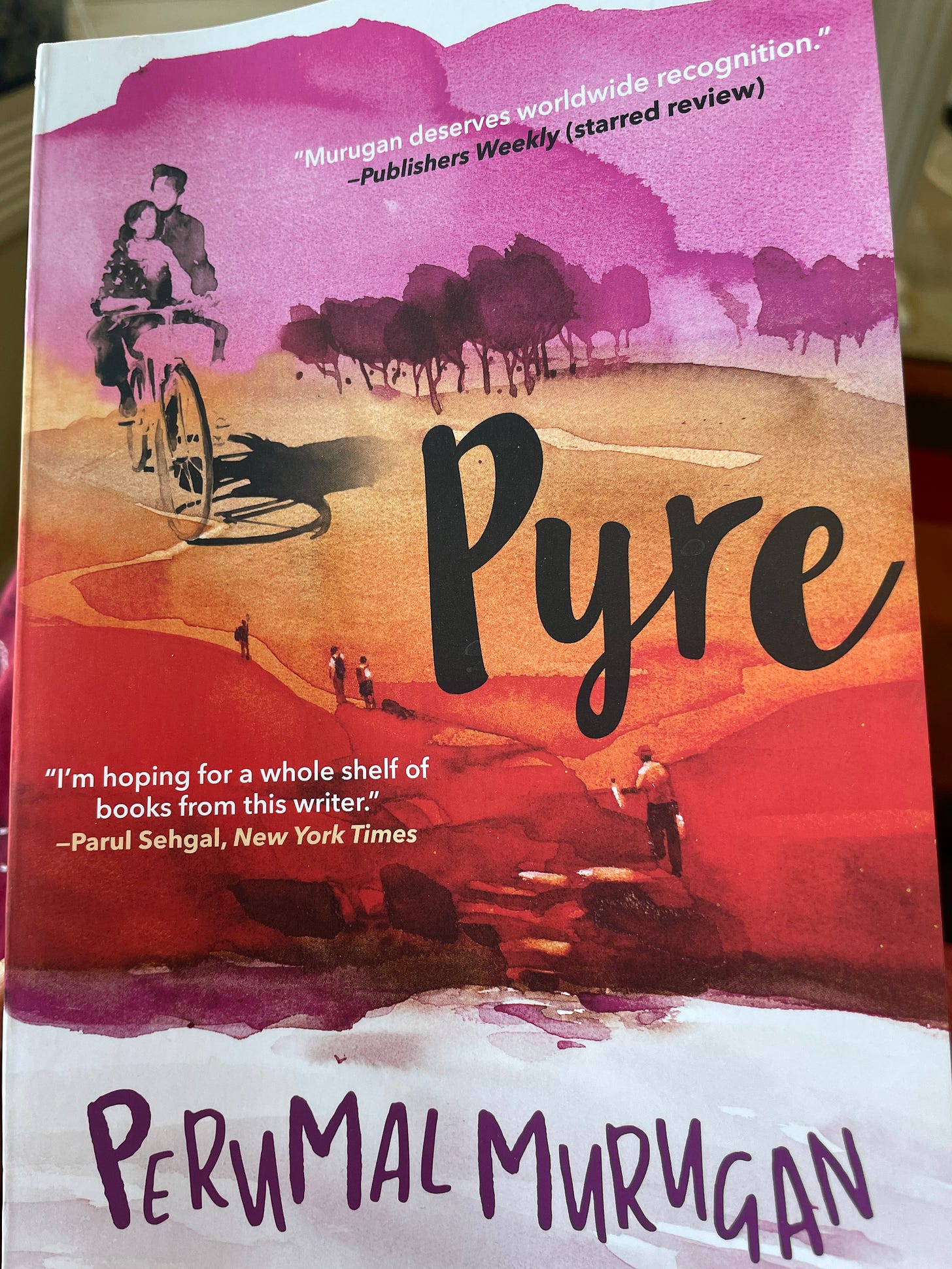

The ending of Perumal Murugan's Pyre is horrific, and what is more shocking is how real and topical this story is in today's India.

Last week, I was at two bookstores in Brooklyn, New York, and I was entranced by both. McNally Jackson and Books are Magic had such a collection of translations that the few hours I spent in each were simply not enough. At McNally Jackson, a flight of steps leads to the world of translated works, expressing, literally, that for those of us working in the world of English, the act of seeking the voices of authors in translation takes a purposeful, concerted physical effort. As soon as I climbed up the stairs, I was floored.

There were entire sections devoted to literature from every part of the world; obviously this included works in English as well as works in other languages. What I loved, however, was the dedication of space to the different cultures. So many parts of the world are now cordoned off to those of us operating mostly in the world of English and while walking through McNally Jackson’s corridors, I realized I’d need many more lifetimes in order to savor all the cultures on display.

“What do you expect, mom?” my daughter said. “This is Brooklyn. So many writers live here.” And what do you know, soon enough I was back at the counter with enough books to fill out my Substack needs for several months. My choice for this week was clear as soon as I spotted a Tamil book in translation.

I find myself reading some writers for how they string words together. There are some others whom I opt to read because they take me to places that will remain inaccessible to me. Author Perumal Murugan belongs to the second category. He is a storyteller with an ear to the ground of the village life of India.

Judging by his body of work, he’s most at home writing about Kongu Nadu, a geographical region comprising of parts of western Tamil Nadu, southeastern Karnataka and eastern Kerala. As the son of a farmer, Murugan grew up in the village and hence he writes about the things that happen within the ramparts of his home and his community. His characters are everyday people trying to find acceptance in society; more often than not, it turns out, they never find it at all.

I read Murugan’s fifth novel, One Part Woman, several years ago and was struck by his simple ferocity. I may not go to Perumal Murugan to learn how to craft a sentence but I will use his narrative gifts to understand just how to tell a story with utmost economy and urgency. In the end, the story always triumphs over the “telling” of it. Murugan’s masterful storytelling subscribes to all the six tenets laid out by the late Anton Chekhov: no verbiage, objectivity, truthful description, extreme brevity, audacity and originality, and compassion.

One Part Woman was set in Murugan’s native town of Thiruchengode, and dealt with a couple, Kali and Ponna, who were humiliated because of their barrenness. The novel portrays their eventual participation in a chariot festival during which, for one night every year, the local community in the novel relaxed taboos and allowed sexual relations between men and women. While the novel received critical acclaim, religious Hindu groups objected to the fictional portrayal of traditions; copies of the book were burned and an official complaint was lodged demanding a ban against the book. At the end of the shenanigan, Perumal Murugan’s name was well-known in literary circles within and outside India.

Murugan’s work is always a reminder that the most authentic voice in Indian writing is in the vernacular. I felt that after reading Munshi Premchand’s Godaan, a story describing the predicament of Hori, a poor farm laborer toiling in the heat of a village up in the north of India, whose unattainable dream is to own a cow. If Premchand is a garrulous storyteller who doesn’t shy away from elaborate exposition, Murugan, whose name describes a Hindu deity with a spear, uses his writing instrument to pare everything down to its barest, searing minimum.

“There was not a soul on the road. Even the birds were silent. Just an ashen dryness, singed by the heat, hung in the air. Saroja hesitated to venture into that inhospitable space.”

~~~From the opening page of Pyre, by Perumal Murugan.

Translated from the Tamil original by writer Aniruddhan Vasudevan, Pyre reminded me of Thakazhi S. Pillai’s masterpiece in Malayalam, Chemmeen. Both works are short. They’re piercing. They seem to end before they should end. Both deal with the travails of the underprivileged, forgotten sections of society. They remind us that there are unseen links that tie society to nature and god. If you displease your family, you incur the wrath of the society, the ruling goddess and nature herself. Both Pyre and Chemmeen have a timeless aspect to them. Their message is clear, that a human is fettered by the framework of societal expectations: in order to belong, you must sacrifice.

The storyline of Pyre is a cliche for those of us who grew up watching Tamil movies set in the hinterland. We aren’t easily swayed by love stories that are doomed from the outset. Saroja and Kumaresan fall in love even though they’re both are from different castes. After meeting in a small southern Indian town where Kumaresan works at a soda bottling shop, they marry at a temple in the presence of his friend before returning to Kumaresan’s family village. Kumaresan warns Saroja to be guarded for their union is taboo in the village.. What the couple does not realize from the outset is that Saroja’s physical beauty and the color of her skin is a dead giveaway about her origin. She is different, that’s all, and quite clearly, an outsider.

The reception Saroja and Kumaresan receive upon arriving in their village sets the tone for their story. Kumaresan’s mother, Marayi, sings a dirge on their first evening in the village predicting that doomsday has arrived. In the weeks that follow, Marayi sounds the death knell again and again, ululating when she cooks, when she tends to her goats, and always, of course, when Saroja is in earshot, beating her chest in sorrow to just about anyone who will listen.

Murugan’s theme is popular in stories about India’s villages. Yet, it’s the handling of such a hackneyed story that drew me in completely. His voice is plain. During conversations, I felt I could actually sense the Tamil behind the curtain of English. I was moved by the sweet moments of love between Kumaresan and Saroja. Kumaresan is dredged out with so much care. It’s a nuanced portrayal of a man who is who he is even though he belongs to a community of macho uncles and lecherous men. In a patriarchal society, Kumaresan grew up without a father. He never learned to be abusive either to the mother who raised him or to the girl who ran away with him. He is civil to his mother even when she is at her most vindictive. Alas, everything in his upbringing leads to the climactic moment when the love of two people simply will not transcend the hate of all the villagers. The ending feels inevitable and we were ready for it—right at the beginning—for the title of the book is ominous.

Murugan juxtaposes the tenderest of moments against the most violent of human interactions. He builds tension by interleaving past and present. As Marayi’s animosity towards Saroja mounts with every day, we are led back to the days of romance in the city where Saroja and Kumaresan fell in love.

The gravy his mother made was very watery, like rasam. He could drink it up. But this kozhambu was different; it was thick and flavorful. Even a small amount was enough to mix with a lot of rice. He wanted to enjoy such pleasures for the rest of his life. When she returned home that afternoon, the little pot with the lid on it was outside her door. She picked it up and went inside. There was a small note inside the sparkling clean vessel. “I wish for this to last forever. Is that possible?”

We know the answer to that but we wish to keep reading because just once in a long while, fiction may indeed be stranger than truth.

I, too, was singed by this book. Thank you for this fabulous review. Translation opened up the world to Perumal Murugan in some unexpected, and sadly, distressing ways, but thankfully the worst is over for him (I hope!) and he is reaping the rewards of literary recognition which he so richly deserves.

What a wonderful and poignant window to the story of this book. Kalpana, you have an amazing gift of zeroing on the right author and their best work and then making it accessible to people like me, who would never know such gems existed without you! For that I am truly grateful. The very title of your article, Singed by the Heat of the book, captures the pith of what you blog is yet again, this time! Awaiting your next installment of yet another gem, Kalpana. And, Thank you!