THIS WILL GET YOUR GOAT

The urban slang for “Greatest of All Time” is right on for this classic about a black goat. This is a book for every shelf.

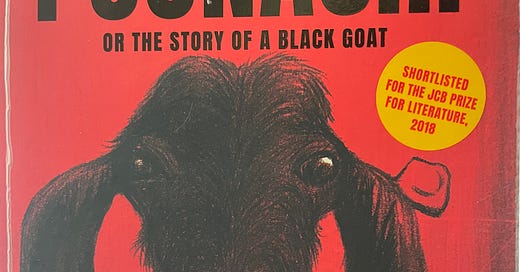

By the time I came upon Perumal Murugan’s Poonachi Or The Story of A Black Goat, I’d already read two books by this author, both of which I found memorable. Pyre moved me immensely when I read it last summer. Its translation by Aniruddhan Vasudevan seemed even more hewn and polished than that of One Part Woman and it left me wondering whether the smoothness I perceived was the writer’s own advancing craft or the gifts of the translator himself.

When a translation is seamless, the story’s hold over the reader is akin to a noose around the neck. Like Poonachi, our hapless goat on Odakkan Hill, I was now a slave, too. Murugan only had to tug one end of a sentence and there I was tearing up and bleating soundlessly at what was about to happen in the tale.

Translated by N. Kalyan Raman, this book may simply be read as the story of a goat. This runt of the litter, Poonachi, is invested with the mysterious power of delivering a big litter. From the beginning, Poonachi’s origin remains a mystery but we suspect divine intervention all along. She’s the physical manifestation of a boon that has been granted to an old farmer and his wife. The writer thus prepares the stage for the follies of human beings. It turns out (and don’t we know it) that when times are good, humans rarely ever realize how good they have it.

When it rained heavily, they cursed. “Why is it pouring like this?” They were fed up of having to protect their possessions from the rain and getting drenched whenever they stepped out. But even an enemy should be welcomed with courtesy. If we curse and drive away the rain that brings us wealth and prosperity, why should it ever visit us again.”

Situations force our hand, no doubt, but the decisions we choose to make when the times are good (like saving for a rainy day, literally) and the thoughtfulness we show early on, can carry us and help us coast during periods of pestilence and drought or personal deprivation. Thus Poonachi, while being the story of a female goat in Tamil country, is really the story of man’s fickleness just about anywhere in the world. Every day, we lead a life of choice. We have the choice to seek and strike a balance. Challenges may appear in many different forms through the course of our lives.

In the life of Poonachi’s adoptive mother, her imminent challenge, just as the book opens, is to try to get our limping, tiny kid, Poonachi, to feed so that she may live. What we realize soon enough is that the world of goats is not that much kinder than the one humans have built for themselves. The nanny goat won’t suckle shaky little Poonachi. She’ll only feed her own kind. Equal access to an udder does not translate to equal opportunity. The nanny goat detests the black fledgling in the barn and ensures her children spurn the guest at the teat.

The goat didn’t at all wish to suckle this kid. She would try to break free and run. But the old woman woudn’t give up. The moment she woke the goat to suckle Poonachi, all her three kids would come running. Pushing them away was hard. When all three of them butted the goat’s udder, inserting Poonachi in the middle was difficult too. She couldn’t put them inside a basket either. If she tried to get Poonachi to suckle while the kids were away nibbling grass in the pasture, the goat would raise her voice and call out to her kids. Wherever they might be, the kids would come leaping and running as soon as they heard their mother’s call.

The old man and old woman may ensure affirmative action by holding the limbs of the nanny goat but to no avail. Soon, Poonachi’s diet must be created out of millet water and she is fed through a feeding tube. She lives, thanks to the resourcefulness, efficiency and empathy of her human mother.

As we follow Poonachi’s life—from childhood to puberty, and from the first flush of romance to arranged copulation and motherhood—we begin to respond to it with all of ourselves, and in a manner that no story about human children has ever commanded. The author magically invests Poonachi with human emotions. The text is so raw and crude in places that I reddened and cringed many a time. Yet it was more real than any story I’d read in any language and at any time. Poonachi is at once shocking and moving, gory and funny, and disgusting and heartbreaking. The black goat’s bedroom may be a beat-up barn or a pasture but the heat is so real. It’s poignant until the last heart-stopping line.

Poonachi’s personal quest for identity and survival reminded me of my constant assertion of womanhood and selfhood—with my mansplaining husband, with my American-born children, with family members who brandish their patriarchal spears at me, and with the world at large. The rope around Poonachi’s neck reminded me of of the plight of many humans I knew, marriage or servitude having rendered some both headless and voiceless.

Poonachi’s terrific translator is the award-winning N. Kalyan Raman who has been translating Tamil fiction and poetry into English for the last two decades. He received the Pudumaipithan Award in 2017. In 2022, he received recognition from the Indian government—the Sahitya Akademi Prize for Translation 2022—for the English language translation of Poonachi.

Last evening, I was fortunate enough to spend a few hours talking to Kalyan Raman in his home in Chennai. I found out that some of the Tamil fiction writers he has made accessible to an Anglophone audience include the late Ashokamitran, Devibharathi, Vaasanthi and Poomani. I cannot wait to read all his literature in translation.

At the end of one full year of reading, I’m compelled to say that this classic animal tale has now floated to the top of my list. The term “GOAT” springs to mind. On social media, whenever I’ve seen rapid fire exchanges during sports games and concerts, the term “GOAT” rises up again and again. This urban slang for “Greatest of All Time” is right on, after all, for this classic about a black goat.

“I am fearful of writing about humans; even more fearful of writing about gods. There are only five species of animals with which I am deeply familiar. Of them, dogs and cats are meant for poetry. It is forbidden to write about cows or pigs. That leaves only goats and sheep.”

~~~ Perumal Murugan in The Preface to Poonachi Or The Story Of A Black Goat.

Like Charlotte the spider, that drew attention to Wilbur the pig, you weave your web of words to shine the limelight on a great Tamil literary contribution by the author Perumal Murugan. Thanks to Kalyan Raman who has helped Poonachi bleat in a more universal language! My question now is should I read it in Tamil or English?? 🤔🤔

Buvana Sharma