BENGAL TALES TO REMEMBER

Each classic story in this collection will burrow its way into your heart.

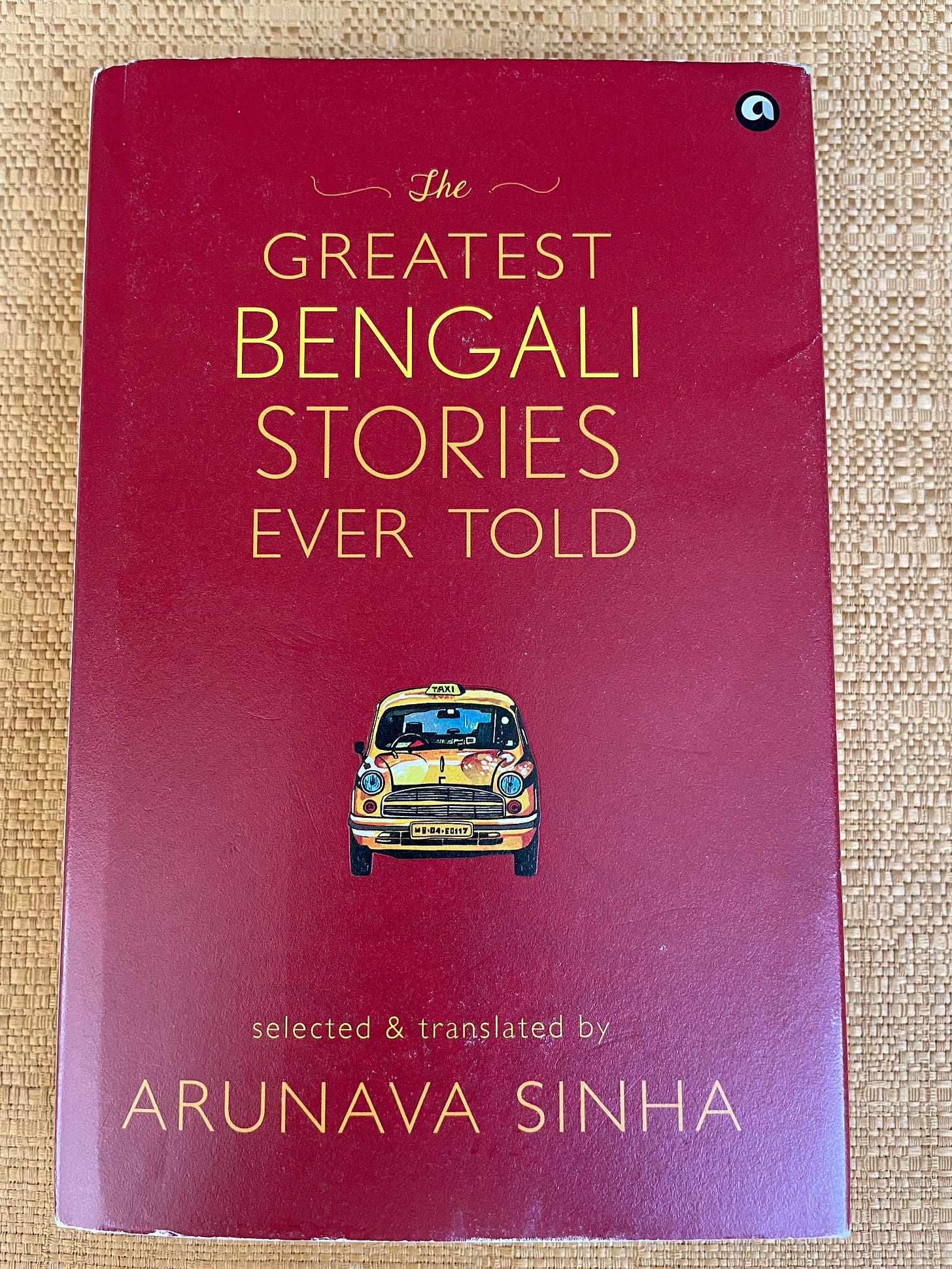

Days after I landed in Kolkata in 2016, this collection of Bengali tales, its cover so emblematic of Kolkata, reached out to me from a shelf at Oxford Bookstore and I bought it right away. At the time, I was traveling through several parts of India to learn as much as I possibly could about the reach of the English language in the country of my birth.

I had just then been introduced by email to a writer and translator named Arunava Sinha—I wrote about his translation of Sankar’s Chowringhee—and he had agreed to give me some time when I flew next to New Delhi. Imagine my thrill when I came upon this newly published collection of 21 short stories selected and translated by Sinha. From one of Rabindranath Tagore’s most revered stories, ‘The Kabuliwallah’, to stories by Tarashankar and Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Buddhadeva Bose, Ashapurna Debi, Premendra Mitra, Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Mahasweta Devi, Sunil Gangopadhyay and Nabarun Bhattacharya, among others, this book includes stories from all walks of life.

The stories in this collection were handpicked by Arunava Sinha who grew up on Bengali short stories. In a thoughtful introduction titled My Love Affair with Bengali Stories, Sinha says his mother read to him. While she loved reading, however, she did not much care for reading out loud and he writes about her special relationship with each little story.

“A short story, to her, was almost like a guilty secret, something she hugged to herself. She would consume these delicacies at a single sitting, unlike novels, that stretched out interminably.”

I love the imagery in his words. They evoke the sweetest memories I had of Kolkata’s delicacies, rosogollas, savored one at a time, as they squeaked on the tongue. Like those famous Bengali sweets, the bite-sized tales in this book are potent. Like Arunava Sinha’s mother, I too love the immediacy and power of a short story told well.

A short story holds an entire world inside it and holds me in its spell in the duration of it. When I read a poignant story, I enter the world of the story and dwell in it until, in the end, I’m ejected, sometimes, with a sharp kick. I want to emphasize this point—about whiplash—at the close of a short story reading experience. I recall writer and teacher Charles Baxter’s commentary on how the ending of a successful short story should seem inevitable and, yet, hold a surprise in it.

Every tale in The Greatest Bengali Stories Ever Told has this quality of an ineffable moment, one that alters the lives of the characters forever, and an ending that is as unsettling as it feels right. In Raja, Ritwik Ghatak’s tight narrative about a brilliant poet, his mother’s sudden death triggers his decline as well as his greed for money. There’s no one around to care or challenge Raja; soon, he sinks into depression and his aspirations tank.

The story does not linger too long in the past; in any case, the past is spun to perfection by Raja when, years later, he meets his college friends. In every lie Raja utters to impress, we feel the weight of his anguish, of what could have been had it only been another way. The story ends exactly as it should have. By the time we reach the end of most of the stories, it’s clear that the character’s plight always circles back in some way to the unknown errors of his or her life. Sinha describes his intent.

“Somewhat fortuitously—I wish I could claim that it is by design, but, frankly, it’s not—the stories here collectively show the rich variety to be found in Bengali literature—whether in terms of form, voice, settling or subject. In all of them, though, I find one particular quality that haunts the characters, and me. It is the sense of something missing, and the search for it.”

How do we describe the eternal note of sadness in the heart? In The Kabuliwallah, one of Bengal’s iconic short stories penned by Tagore, a vendor from Afghanistan strikes up a friendship with a young child one day when he walks down the road to sell his wares. Minnie is his daughter’s age and every day, when he passes her home, he makes time for her, dropping off some dried fruit on each visit. They look forward to their time every day but their bond is broken one day in an unfortunate incident; a magical relationship is lost forever for both the child and the vendor. Years later, when the man stops by to visit Minnie, she has blossomed into adulthood and is already married.

The Kabuliwallah is about loss that’s always around the corner. It’s about every connection we make as humans and the recognition that this joy, too, is fleeting and must evanesce in time. I recognized the special moments in my own life when, suddenly, the magic was destroyed forever.

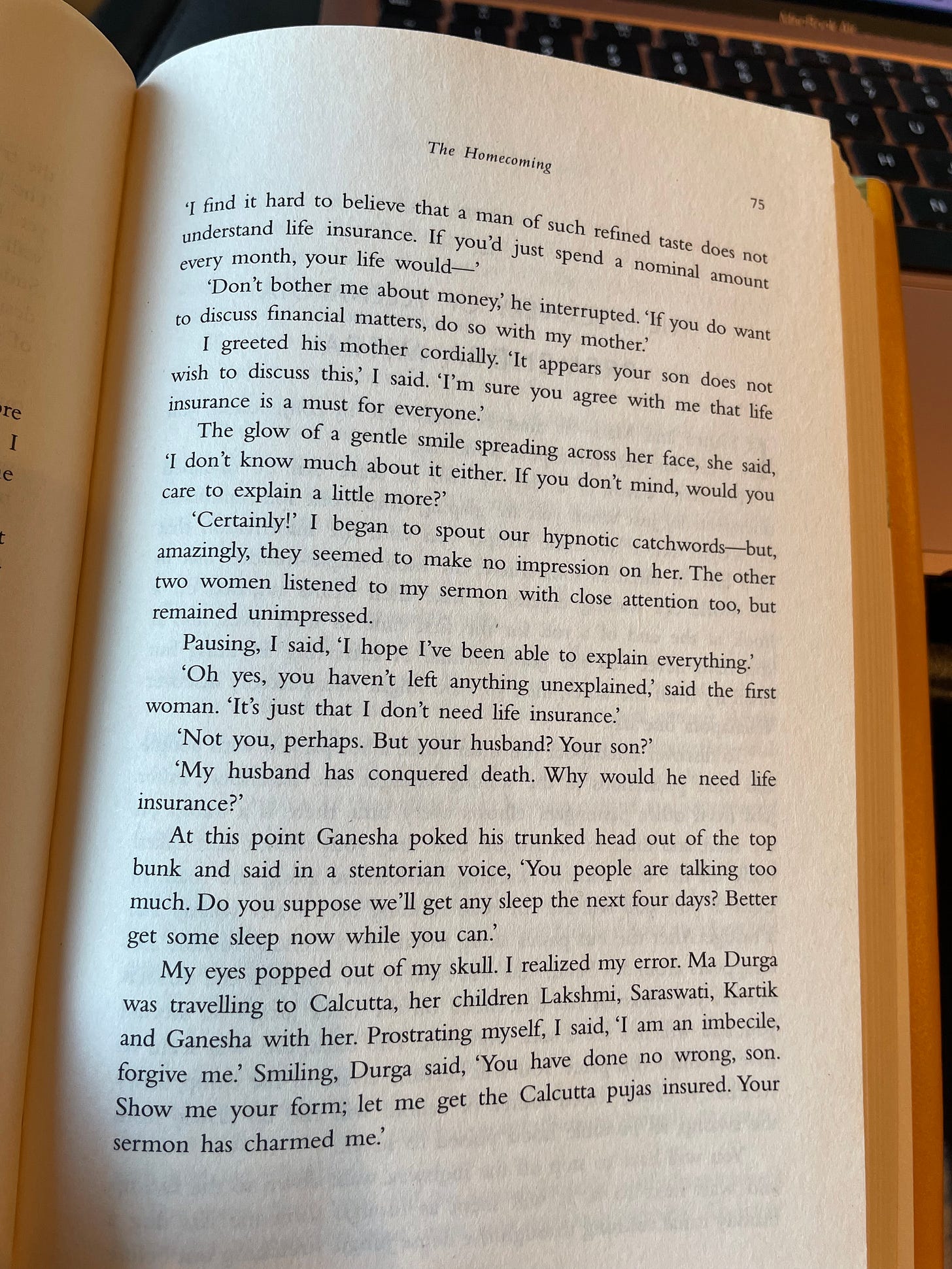

One of the loveliest, upbeat stories in this collection is a tale by the late Banaphool who was known for his fantastic fiction. The pen name of Balai Chand Mukhopadhyay, “Banaphool” means “wild flower” and it was adopted by him to hide the fact of authorship from his tutors. He was a novelist, short story writer, poet, playwright and physician. Banaphool was prolific. In a productive period of sixty-five years, he published thousands of poems, 586 short stories (a handful of which have been translated to English), 60 novels, 5 dramas, a number of one-act plays, an autobiography, and numerous essays.

I’ve attached a two-page short story by Banaphool, Homecoming, that’s such a delight from beginning to end thatI have no doubt that by the time readers reach the last line, the reaction will be surprisingly typical: “Oh My God!”