SO MUCH TO SEE

A two-day road trip with friends to Yosemite National Park reminded me of the bounties of nature in these United States. There is so much to see—and to receive.

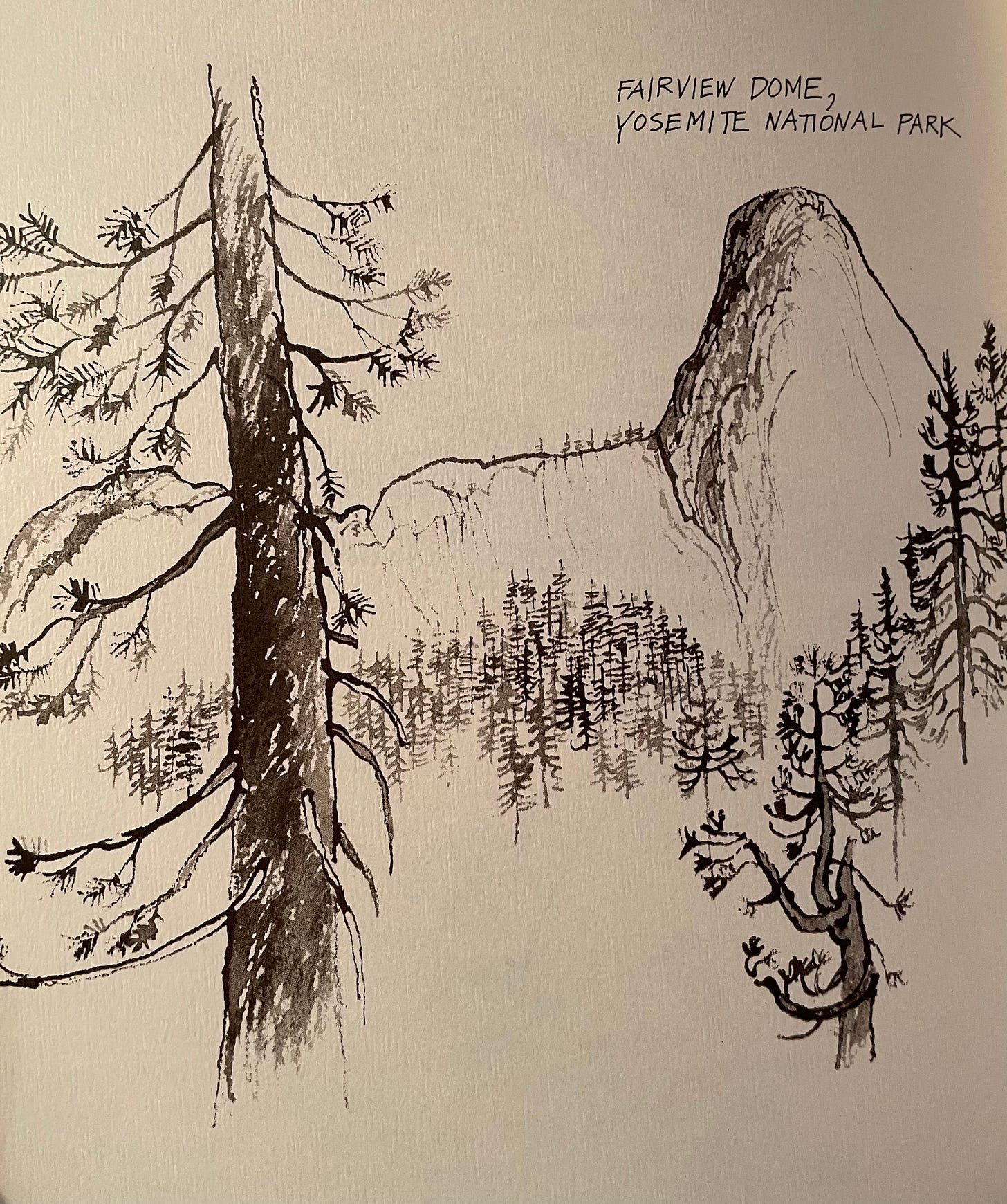

Last Wednesday, my husband and I set out towards Mariposa, an old, historic town in California, with two of our longtime friends. Our buddies of five decades—Jayadev, an avid photographer with an enviable collection of ancient and new cameras, and the other, Shanthi, a painter who refuses to paint except under duress—have made it a point to see as many of the national parks in the United States as they possibly can. They are both into wildlife, too. They chase hummingbirds, geese, blue jays, herons, bald eagles, white-tailed kites, plovers, snowy geese, ducks of all stripes, turkey vultures and sand hill cranes in and around Silicon Valley just like the valley’s tech moguls chase funding for their companies.

In a Silicon Valley known for its material pursuits, Jayadev has opted, instead, to chase the spiritual, save for the occasional margarita. I know of late night trips he has made chasing “moonbows” at Yosemite’s waterfalls. At difficult times I know he has sought solace at the Krishnamurti Foundation of America in Ojai valley. I often find this husband and wife duo at places that escape the radar of those who seek only Northern California’s material offerings.

When we began talking about our trip to Yosemite, Jayadev told us to think about getting a membership with the National Park Service. We realized that a lifetime membership (for those age 62 and above) of $80 would give us access to many historic sites in these United States. I felt that it would, at the very least, motivate us to visit America’s national parks and push us to learn more about the country that had given us so much over the decades.

After almost twenty years, my husband and I were back again at Yosemite. We were aghast that we had not visited this local treasure more often. In 1987, Shanthi, Jayadev, my husband and I had piled up into our Toyota Camry and driven to many spots in Northern California. Keeping us company was another dear friend, a scientist classmate of mine, Meena, whose face had been plastered all over Times Square when her company went public during the pandemic last year. Thirty-four years later, just as we were coming up against the new challenges in our older bodies, we were back in a place that held so many memories for the five of us. I felt that the brittleness of aging had crept into Yosemite, too even though, viewed against geologic time at Yosemite Valley, nothing had really changed since 1987. Still, for me, it looked different.

I had not seen Yosemite look drier. In the brooks and creeks, all I saw were more rocks than water. The waterfalls were far fewer. Bridal Veil Fall was a streak now. Shanthi told me how, compared to what she had witnessed one February three years before, this was disappointing, owing, in part, also to this year’s drought. Nevada Fall still seemed substantial and stunning, especially from the magnificent lookout at Glacier Point. Vernal, however, was a ribbony trickle. The majestic rocks—El Capitan, Cloud’s Rest, Half Dome, and Liberty Cap as well as the lesser rocks—glinted against the sun, unchanged.

As my husband and I stood at Olmsted Point talking to a mountain climber, Shanthi joined us to tell him that her ultimate goal in life was to conquer Half Dome. I listened to the two of them as they talked about that perilous hike, reflecting on how my ambition, before I died, was simply to read all the bodies of work by my favorite writers.

“My heart rate resembles that of a marathon runner,” Shanthi said to Stan, the climber.

“Oh, yeah?” he said. I detected a little skepticism in Stan’s voice as he proceeded to ask her questions about her endurance. He asked her what else she did to keep fit. He informed her that one section of the Half Dome hike consisted of steep stone steps at least a foot in height. She would have to have good knees. It was doable provided she trained, Stan said, reassuring her that all sorts of people of all ages attempted the climb. I interrupted them to say that one of our friends, Guy Lohman—read about him on the piece I wrote about my hometown of Saratoga—had climbed Half Dome a few months before, just before he turned 72. I listened to Shanthi and Stan as they began to talk about Free Solo, the terrific Oscar-winning documentary on Alex Honnold as he prepared to climb the face of the 3000-ft El Capitan without a rope or harness. I remember having watched the documentary holding my breath, as Honnold straddled the fine line between grace and perfection, and gaucheness and death.

“Sausage fingers!” exclaimed a gentleman who had joined in to listen to the discussion about Free Solo. I told myself I must read up about Honnold’s hands later, after I reached home. Incidentally, I did find a story that discussed his extraordinarily large palms and his stubby fingers. I saw a reference to Jamie Lisanti’s story for the Sports Illustrated: “Alex Honnold’s life is in his hands—those freakishly large palms and sausage-like digits, with fingerprints eroded away from years of wear.” Naturally, I’d been curious about Stan’s fingers, too, when he began talking about hands that morning at Olmsted Point.

“So let’s have a look at your hands?” I said. The climber opened out his palms. A few of us felt the ends of his fingers, awestruck that a rock climber like him actually possessed butter-soft fingers. Stan is an electrical engineer. He has guided several groups of climbers up Half Dome. His first trip up had been when he was thirty years old and now he was past fifty. Stan’s frame was taut and wiry and he looked like he could do just about anything he set out to do.

On the other hand, I was built like a plover. I told Shanthi, a few days after we returned from Yosemite, that my body resembled that of the bird: “Short legs. Heavy body. Plump all over. Pert nose. That's me!” Unlike the bird, I had no ambition to fly. Unlike Shanthi, I had no desire to climb anything beyond the ladder that led to our attic.

Shanthi, in direct contrast to me, was unafraid of taking risks and disrupting the calm of her daily grind. Her dream, despite her fair number of physical limitations, impressed me. Climbing Half Dome is not for weasels. A mere one mile hike up to the bridge on the Mist Trail had exhausted me on our first afternoon at Yosemite. I’d felt dizzy and dehydrated, despite the extraordinary amount of walking we had done in Singapore. If I couldn’t handle trudging up a mile (to a thousand foot elevation) on a hot summer day, how was I in any shape to do anything else?

The Half Dome ascent that my friend wished to do was supposed to be an extraordinary accomplishment. It was dangerous, no doubt. The first challenge involved in the hike was building endurance in what would amount to a minimum of a twelve-hour hike. We saw markers on Mist Trail about how many gallons of water hikers must drink on this 14-mile round trip to Half Dome. In addition, this climb— which gains 5000 feet in elevation—includes a mountaineering component at the very end.

The hike begins along Mist Trail and it follows the Merced river up hundreds of steps to the top of Vernal Fall. Just this section alone keeps the Yosemite search and rescue team busy throughout summer, I learned. The rocks along the falls are guaranteed to be slippery. Hiking boots are recommended but people bound up these rocks in footwear that creates trouble and the result is injured knees and ankles. The hike onwards and upwards to the top of Nevada Fall is even more difficult; this is not even halfway, however, to the top of Half Dome.

What follows Nevada Fall is a long, sandy section on Yosemite valley. Rangers warn about dehydration during this hot walk. Then comes another trek through the forest which brings hikers to the steps of the Sub Dome. Climbing the Sub Dome to the base of the cables is nearly as challenging as the cables to Half Dome itself. At this point, a hiker is at an altitude of 8000 feet. The air is much thinner. The cable ascent for the last 400 feet to the top of Half Dome can be daunting in bad weather. Rain or thunder are not unusual on a summer day and water can make the rope slick. Lightning and metal don’t mix and the cables can become electrified. During this last ascent to the summit of Half Dome, a hiker cannot stop because of the long queue of others trailing him. As I learned about all this, I began having a panic attack just visualizing my friend doing this climb.

Sometimes I wondered why people like Guy and Shanthi held on to such dreams. Why did some people want to climb the Everest before they died? Even when I was 8, 18, 28, 38, 48 or 58, I’d never wanted to die doing something before I actually, really, died. Why was I happy to be an armchair climber while Alex Honnold’s hands groped the rocks for a fissure one mile above the ground? Was I a wimp if I didn’t aim for the impossible? Was I a weasel because my only goal in life was to achieve a daily maximum target of 10, 000 steps in and around Saratoga?

When I returned home from Yosemite, I began reading DUTCH COURAGE, a short story by writer Jack London in which two young men attempt to climb Half Dome; they’re many thousand feet below Half Dome, cooling down in the waters of Mirror Lake when they sense that someone up at the summit is in trouble. Between sips of whisky, they manage to make it to the top to find the man. Jack London’s story inspired me to read up on the first man best known for making the first ascent to the summit of Half Dome on October 12, 1875.

During his climb, Scotsman George G. Anderson drilled holes on the rock without the advantages of modern climbing gear or techniques. After 1919, the iron spikes he placed on the rock housed the cables for the popular route up Half Dome. In November 1875, after Anderson passed away, John Muir, America’s most famous and influential naturalist and conservationist, traced his path and climbed Half Dome (originally called "Tis-sa-ack", meaning “Cleft Rock” in the language of the local Ahwahnechee people).

For my part I should prefer leaving it in pure wildness, though, after all, no great damage could be done by tramping over it. The surface would be strewn with tin cans and bottles, but the winter gales would blow the rubbish away. Avalanches might strip off any sort of stairway or ladder that might be built. Blue jays and Clark's crows have trodden the Dome for many a day, and so have beetles and chipmunks, and Tissiack would hardly be more "conquered" or spoiled should man be added to her list of visitors. His louder scream and heavier scrambling would not stir a line of her countenance. ~~ John Muir, “The Yosemite”

I came upon Muir’s writings on Yosemite and I’ve been moved by his love for nature. Muir’s concerns about allowing human beings to discover the wonders of Yosemite are hardly unwarranted. Many of the passages of fine writing hold even more meaning over a hundred years later when, thanks to global warming, the glaciers are retreating. I watched a video on the glaciers of Yosemite National Park and it’s a frightening commentary on the slow and steady unraveling of nature.

When times are tough, most of us turn to nature for reassurance. During our time at the park, we talked with our friends about the things derailing our lives. In the last year, we’d watched their stoicism while they struggled with the logistics of elder care in India, the complexities of travel to India during a pandemic, and the challenges of the end of life for aged parents during an uncertain time in the world. Last month Jayadev lost his father—during the height of Covid-19 in India’s Chennai—exactly a year and ten days after his mother passed away.

Our trip to Yosemite last Wednesday was a reaffirmation of why people drove up there every few years to stand in the presence of the old stones. The granite monuments of Yosemite always made us see our problems in light of the larger events in the manmade and the natural world. El Capitan always managed to flatten our ego. It was impossible, in its presence, to not acknowledge how inconsequential we were in the universe. It was impossible to not swoon at the beauty and grandeur of it all.

Wonderful piece my dear friend. We were humbled at the beauty and grandeur of Yosemite. The Tuolumne meadows, Glacier Point, Half Dome and all its faces tugs at your heart that doesn't want to leave. Yosemite will never get old. The memories of our first visit together added to the fun and nostalgia. Muir and Alex in one piece was brilliant. The ending was as imposing as El Capitan itself.

Love it. So grateful I read it. Proud of you my neighbor 😘