SO MANY MORE LIES—AND PAGES

When the flatulence of a book cannot be justified, how can one not balk at the hubris of a writer who imagined that readers would stay loyal to her until the very end of a story?

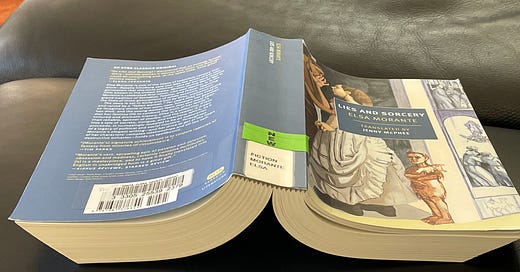

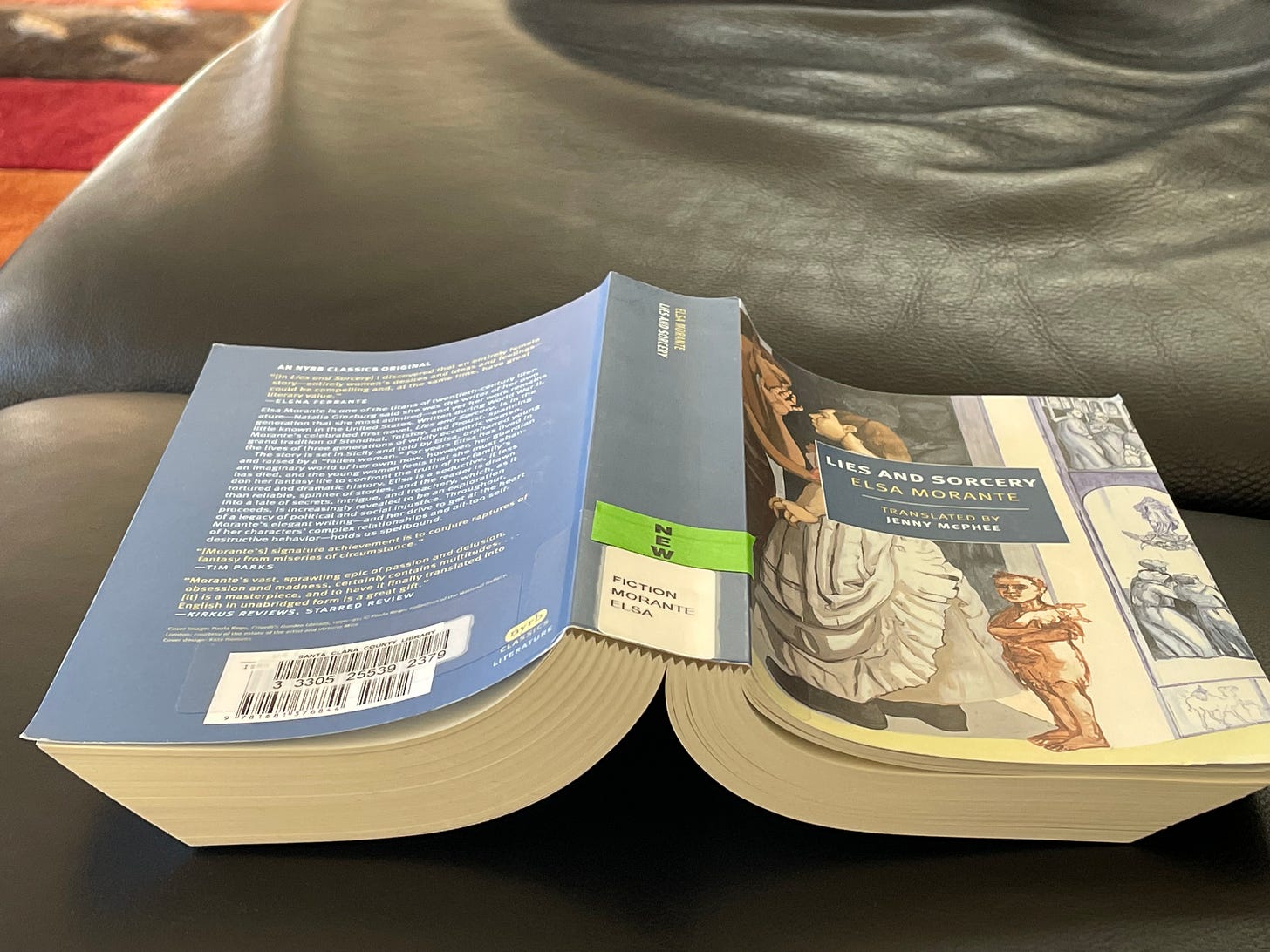

I was really excited about having picked up this book. Last week, I introduced the first 300 pages of Lies And Sorcery and wrote about the first section of the book. As I trudged through the next many hundred pages, however, one question kept popping up in my brain. Was there a reason this story could not have been hammered to a third, if not a FIFTH, of its size?

Having finished the book, there’s nothing that I found in this oeuvre that could not have been whittled down to a kinetic 300 pages to narrate the ill-fated love story of Anna and Edoardo, two cousins whose parents are siblings (Anna’s father is Edoardo’s maternal uncle). Instead, we move through it at a decrepit snail’s pace, hobbling towards an end that is both unsatisfying and desperately contrived. This was like my homemade yogurt gone bad, its stringy elastic consistency stretching with threads that travel from Peshawar to Kanyakumari. The story felt like yesterday’s gum in today’s mouth. I’m still annoyed at myself for having stayed with the work.

A recap of the story has to begin with the siblings (Anna and Edoardo’s parents) who are estranged owing to a longstanding family feud which the author does not share at any length. Anna and Edoardo grow up not being acquainted with each other although Anna (being from the poor side of the family) knows some details about the life of her cousin. Edoardo, the bratty and handsome male, knows almost nothing about Anna. When they do happen upon each other, however, the attraction and the passion is intense. It’s somewhat theatrical and otherworldly, and it’s clear from the outset that Edoardo (and certainly his mother) needed psychiatric intervention from the cradle.

Edoardo is a toxic boor. He cannot love the way most human beings love. He is so self-centered and vain that when he loves someone, he destroys the feeling and the person along with it. The deeper he falls in love with Anna, the surer he is about not wanting to love her. There’s more, however, to his vicious nature. What will ultimately remain elusive to him, others may never have, at least not completely, and he will do everything in his power to ensure that this is so. If there is a book about villainy, this surely is it.

Thus Edoardo turns around to destroy a friendship he begins with Francesco, a young man he meets whose father he knows from the past. Like Anna and many others, Francesco, too, becomes a pawn in Edoardo’s life. When he discovers that Francesco is in love with a “whore” (Rosaria), he makes sure to befriend her, destroying the relationship between Francesco and Rosaria. In the meanwhile, he drives Francesco towards Anna who, obviously, doesn’t want him until, of course, straightened financial circumstances propel her in his direction. Anna marries Francesco out of sheer necessity and the marriage is marred by the shadow of Edoardo (in Anna’s case, at least). Francesco is deeply in love with Anna and is more than willing to be a doormat to her and hopes, like all sorry humans, that she will requite his feelings some day in their future.

By the time the story barrels to its end, Anna, upon discovering that Edoardo has long been dead, begins to lapse into a trance-like state during which she writes impassioned letters dictated by Edoardo to her.

Anna’s imaginary adultery, no less than a real transgression, had changed her entire physical appearance. After the scenes with Francesco and all the mortifications and insults, she had an ambiguous air about her, the one of involuntary suggestiveness and remembered pleasures that loose women give off after a rendezvous. Her face was soft and a little tired, her lips parted and plump as if they preserved the imprint of recent kisses, and her elusive, languid, and glowing glances seemed to be inspired by recent visions of love.

This is a tragedy of errors pre-wrought by Edoardo whose raison d’etre is to engender chaos, long after he is six feet under. Soon, Francesco is unwittingly sucked into Anna’s imaginary world, and he, too, begins to be suspicious and deluded about an extra-marital world of deception and treachery where there is virtually none. Unhappy and derelict, and awash in debt, he dies soon after in a gruesome rail accident.

The overarching message of Lies And Sorcery is the tragic consequence, echoing through the generations, of poor relationships marked by serious emotional deprivation. Lies And Sorcery is also pre-occupied with the idea of piety and expiation. In a home in which a mother is deeply devout, Satan is alive in the form of a son, Edoardo, who is a vampire roaming the earth, in life and in the after-life. In a grand irony, expiation remains unachievable to all these characters, who, had they been born in India, would have been ferried on a bull by the Hindu God of Death, Yama, to a place where multi-headed demons with many wretched gifts would have spiced up and fried their heads.

By the time I closed the book, I was no more enamored of the voice of the narrator. As the story progressed, the voice of Elisa, Anna’s only child, seemed less believable. While the voice is unusually mature almost the entire time, in a few instances, especially while delving into sex and marriage, her tone is suddenly childlike, as if the author realized, all of a sudden, how little a pre-pubescent child should really know about conjugal life.

In late October, during the South Asian Literature and Arts Festival, attendees could not stop talking about Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water. I asked one of his devoted readers whether (and how much) she had enjoyed his latest book. The length of that book made me wary of picking it up, given that I was already reading a lot during a given week. It was clear that my friend had loved it. But did it have to be that long, I asked. Her response arrived pat. “Oh, the book could have been one-fifth of its size. But you know how…. I think writers like Verghese simply enjoy the process of writing….and more writing.”

On the surface of it, my friend’s comment seemed flippant. Yet so many writers choose to be verbose and garrulous when they could, in fact, be terse, and thus more effective. It’s an eternal struggle for all writers, to “kill one’s darlings.” Yet there must, however, be a band of writers who believe that the more they write, the more others might assume they have something of value to say. I’m surprised that this book was published the way it was. According to Jenny McPhee, the translator of Lies And Sorcery, Elsa Morante was upset with her publisher when, in 1951, her novel was whittled down by many hundred pages from her original.

In 1951, the novel was published under the title HOUSE OF LIARS, in a translation by Adrienne Foulke, with the editorial assistance of Andrew Chiappe. More than two hundred pages were cut in this version, causing Morante considerable grief, which persisted for the rest of her life. She called the translation, a “mutilation,” a '‘massacre,” “unrecognizable,” and “hurtful.” She wrote letters of protest to Giulio Einaudi, her publisher, in which her distress is plain. ~~~ Jenny McPhee

I went back to read what I had written about the book last week. I had obviously been struck by “its masterful pacing and its scorching assays into human character”. However, true as it may have been in that earlier half, beyond the 300-page mark, however, I felt I was in free fall.

This could have been a terrific work with deep psychological insights into patriarchy and women’s suffering at the hands of parents, siblings, lovers, spouses and children. In my view, the tale lost its power and its magic with the endless peregrinations around the life of each character, and expositions that rototilled the same material even when observations should have been boiled down to a single line. A recent review in the New York Times made no reference whatsoever to the flatulence of the pages.

“What made this door-stopper of an Italian soap opera feel like great literature to large numbers of sophisticated readers 75 years ago? The same thing that makes it wonderful today. The writing, pure and simple. Each plot development is surrounded by acres of commentary whose richness and intensity — deep, dense, psychologically penetrating — provides the story with transformative values, converts melodrama into metaphor.” ~~~ Vivian Gornick, in her review of LIES AND SORCERY in The New York Times

Surely there must have been any number of readers who abandoned this novel after the first three parts? I stayed with the book for precisely one reason. If I did not abandon Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet (about 1500 pages) last year, there was no way I’d leave midway through the work of Ferrante’s mentor.

Morante is clearly a terrific observer of people, mores and temperaments but halfway through the book, I was tired of the characters and the repetitive behavior of many of the key personalties. I was fatigued by their wicked ways and unwilling to excuse anything that happened anymore to anyone in the story.

When I put this book away, two images swam into focus in my Morante-addled mind. Her ideas, initially brimming with nuance and depth, had now became vacuous and turgid, like cotton candy spun and sold everywhere in Mexico City on The Day of The Dead.

“Yesterday’s gum in today’s mouth.” Has there ever been a more damning assessment of a piece of writing? Ouch! Thx for saving me the trouble! I’m tantalized by your reference to Verghese’s latest, though. I didn’t balk for one minute while reading Cutting for Stone. Am I in for a wordy letdown?

I hear you, Kalpana. Length isn’t the only problem when writers are allowed to be self-indulgent. I’m trying to read a novel by an author whose previous two books I tore through and admired. This one is long, slow, and riddled with sloppy grammar (not the kind that reveals character) and uninspired sentences.

I haven’t read Elsa Morante, but your review has made me curious. I may pick up the Italian version and see how it goes.