SAVED BY GOGOL

The artistry of this writer's writer made me gasp. Nikolai Gogol was dead at 42 but he left behind plays, essays, and stories that have been adapted for the stage and the silver screen.

I first realized I must read Nikolai Gogol the day I came across a paragraph about his work in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake. The name of the protagonist’s son in her novel is Gogol. It is significant because it was given to him in honor of Gogol, whose collected stories saved the life of the fictional Gogol's father, Ashoke, in a railway accident in India. Ashoke decided on that name for his son because he believed that he was saved by the pages of the work called The Collected Stories of Nikolai Gogol.

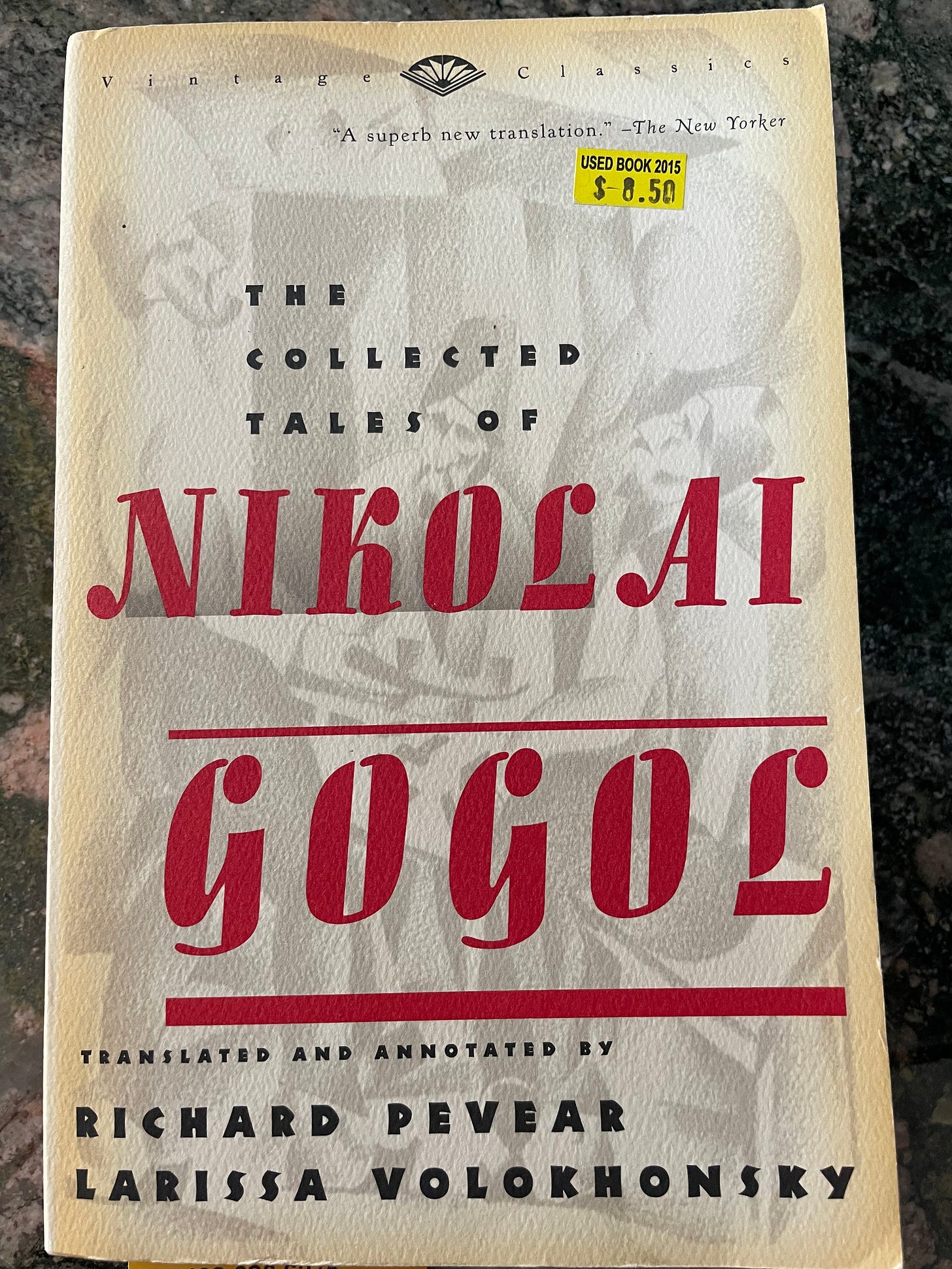

My own edition of the work is called The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol and it’s not hardbound, unlike the edition described by Jhumpa Lahiri. It contains the landmark story, The Overcoat, mentioned in Lahiri’s novel.

But the lantern’s light lingered, just long enough for Ashoke to raise his hand, a gesture that he believed would consume the small fragment of life left in him. He was still clutching a single page of “The Overcoat,” crumpled tightly in his fist, and when he raised his hand the wad of paper dropped from his fingers. “Wait!” he heard a voice cry out. “The fellow by that book. I saw him move.”

He was pulled from the wreckage, placed on a stretcher, transported on another train to a hospital in Tatanagar. He had broken his pelvis, his right femur, and three of his ribs on the right side. For the next year of his life he lay flat on his back, ordered to keep as still as possible while the bones of his body healed. There was a risk that his right leg might be permanently paralyzed. He was transferred to Calcutta Medical College, where two screws were put into his hips. By December he had returned to his parents’ house in Alipore, carried through the courtyard and up the red clay stairs like a corpse, hoisted on the shoulders of his four brothers.

It’s a remarkable moment in Lahiri’s brilliant work and it has stayed with me all these years because in every human being’s story, something dramatic happens to alter the course of lives and relationships. Few are as momentous, however, as the event described in The Namesake that tells us how the pages of Gogol’s book delivered the protagonist from death.

Nikolai Gogol's influence has been acknowledged by many literary mavens, including Fyodor Dostoevsky, Franz Kafka, Vladimir Nabokov, Flannery O'Connor. I found one particularly hilarious observation attributed to a gentleman called Marie-Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé who was a French diplomat, orientalist, archeologist, travel writer, philanthropist and literary critic: “We all came out from under Gogol’s Overcoat.”

I was pressed for time this week and could do justice only to half of the stories in the collection and I focused on the Petersburg stories all of which were written after 1835. I’d read The Nose a long time ago and while I’m not sure I loved it even this second time around, on this reading, I read it with more compassion and with an eye to the moments of incandescent writing.

The collegiate assessor Kovalev woke up quite early and went “brr…” with his lips—something he always did on waking up, though he himself was unable to explain the reason for it. Kovalev stretched and asked for the little mirror that stood on the table. He wished to look at a pimple that had popped out on his nose the previous evening; but to his greatest amazement, he saw that instead of a nose he had a perfectly smooth place! Frightened, Kovalev asked for water and wiped his eyes with a towel: right, no nose! He began feeling with his hand to find out if he might be asleep, but it seemed he was not. The collegiate assessor Kovalev jumped out of bed, shook himself: no nose!… He ordered his man to dress him and flew straight to the chief of police.

The reading experience is different as we age. In 2022, the loss of an incisor left a bad taste in the mouth and everything that happened to me in the last two years has seemed to be far more trivial that the loss of my tooth. I looked back at 2022 in a Substack post I titled The Year of the Tooth.

Beyond the literal meaning of this story, the larger point about the temporary disappearance of a nose alludes to the human tendency to harbor a massive ego. What’s quite stunning is how, when the nose that was lost is actually found by a police officer, the joy is short-lived. Gogol goes on to say, in such luminous prose, that our contentment in any situation is ephemeral, after all.

But nothing in the world lasts long, and therefore joy, in the minute that follows the first, is less lively; in the third minute it becomes still weaker, and finally it merges imperceptibly with one’s usual state of mind, as a ring in the water, born of a stone’s fall, finally merges with the smooth surface. Kovalev began to reflect and realized that the matter was not ended yet: the nose had been found, but it still had to be attached, put in its place.

The collection I read was translated (and annotated) by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky and it was published in July 1999 by Vintage classics. The translator’s note in this book is an illuminating read and it made me realize a couple of things. Nikolai Gogol was already famous in St. Petersburg by the time he turned 21. (Note that he died by the time he was 42.) Not only that, he wrote both “Ukrainian Tales” and “Petersburg Tales” and it seems that he was an outsider with a local perspective in both Petersburg, and in his own Ukraine, too, a feeling that resonated with me completely. I feel as if I’m an outsider in India, the country of my birth, and in America, the country of my adoption. I’m comfortable in both; yet I’m an alien in both for reasons I cannot articulate clearly enough.

While I didn’t enjoy all the stories equally and was at my wit’s end while reading The Diary of a Madman, I’m astounded by the writer’s eye for detail in the daily life of early 19th century St. Petersburg. The opener of a tale called Nevsky Prospect is such an absorbing account of how the eponymous avenue in St. Petersburg changes over the course of a whole day. What makes all these Petersburg stories particularly fascinating for me is how the author sees so much humor even in situations that are mired in pathos and despair.

Sarcasm is certainly Gogol’s strong suit. The description of the art shop in The Portrait is rich with hilarious observations. Gogol has a way of making a place or a person come alive some two hundred years later. The story goes on to describe the people who gawk at the paintings in an art shop.

Nowhere did so many people stop as in front of the art shop in the Shschukin Market. This shop, indeed, presented the most heterogeneous collection of marvels: the pictures were for the most part painted in oils and covered with a dark green varnish, in gaudy, dark-yellow frames. Winter with white trees, a completely red evening like the glow of a fire, a Flemish peasant with a pipe and a dislocated arm, looking more like a turkey with cuffs than a human being—these were their usual subjects.

Just about everyone has their reasons to stand and stare and we learn that “young Russian market women hasten there by instinct, to hear what people are gabbing about and look at what they are looking at.” We begin to understand soon enough that the story is about that which every creator in every field must ponder. Does he want to slave away at his art to become the best craftsman and artist there is, or does he want to bend to people’s perception of what art should be and make money as fast as he possibly can? In the story, we watch the evolution of a man with extraordinary ideas about art fall victim to the sordid attraction of fame and riches.

“No, I do not understand,” he would say, “why others strain so much, sitting and toiling over their work. The man who potters for several months over a painting is, in my opinion, a laborer not an artist. I don’t believe there is any talent in him. A genius creates boldly, quickly. Here,” he would say, usually turning to his visitors, “this portrait I painted in two days, this little head in one day, this in a few hours, this in a little more than an hour. No, I…I confess, I do not recognize as art something assembled line by line. That is craft, not art.”

The Portrait was certainly my favorite from the Petersburg Tales. The exposition felt just adequate and not gratuitous; the twist at the end was simply unbelievable. By the time this long story rolled to a close, we’d learned so much about how to make great art, the creator needs both the moral courage and the grit to be a social recluse.

He disregarded everything, he gave everything to art. He tirelessly visited galleries, spent whole hours standing before the works of great masters, grasped and pursued a wondrous brush….He granted its due share to everything equally, drawing from everything only what was beautiful in it, and in the end left himself only the divine Raphael as a teacher. So a great poetic artist, having read many different writings filled with much delight and majestic beauty, in the end might leave himself, as his daily reading, only Homer’s Iliad, having discovered that in it there is everything one wants, and there is nothing that has not already been reflected in its profound and great perfection.

Hi Kalpana, Gogol is one of my favourite writers, I so enjoyed your post! Many Russians say that it's impossible to appreciate his works in translation, and I have to agree – his pyrotechnic Russian is really unique to him – but it would be a shame not to read him at all. His novel "Dead Souls" is also a masterpiece: https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300060997/dead-souls/ Thanks for this great post!