ON THE NEXT PLANE TO ISTANBUL

This book is a brilliant artistic expression, a work that is as intensely personal as it is universal.

There are some writers I read to learn about something new in the world. There are some others I read to enjoy a gripping story told with unusual grace. Then there are those I read who do both, for they give me so much while never coming between me and their words. These are the writers who teach me how to hone both my mind and my craft. They coax me into being the best writer I can be.

There are so many joys to speak of upon reading such writers: Savoring their words; turning over their ideas in my head; parsing their sentences while reading them aloud several times; rereading entire chapters to visualize the scaffolding of their work in my mind’s eye; returning to the contents page to see how they plotted the narrative arc of their story; and, sometimes, simply picking a section, randomly, to momentarily tug at a thread of an idea on the page.

This week I read nonfiction from Orhan Pamuk who writes in Turkish and works predominantly in fiction. A few months ago I wrote about being winded after reading Pamuk’s THE MUSEUM OF INNOCENCE. I told myself then that there was no way I was going to step into the city of Istanbul without having read his magnificent paean to the city in which he has lived, dreamed and created an impressive body of work. Four weeks from now, I’ll actually be landing in the city that shaped Orhan Pamuk and I’m so glad I actually managed to finish reading this dense memoir translated by Maureen Freely. I feel grateful for living at a time when a writer like him, who is almost a decade older than I am, built a stellar career and went on to win the Nobel prize (in 2006) at 54 years of age.

ISTANBUL: MEMORIES AND THE CITY is a three pronged literary memoir that’s rich and layered—and paced, in the wiliest of ways, to keep us reading until the last page. While it feels like an anatomical study of the city of Istanbul, it’s also a brazen account of the Pamuk family’s struggles and hypocrisies against the backdrop of the ruins of the Ottoman empire. Above all, it’s a masterful story of one young man’s journey into discovering himself and his true vocation.

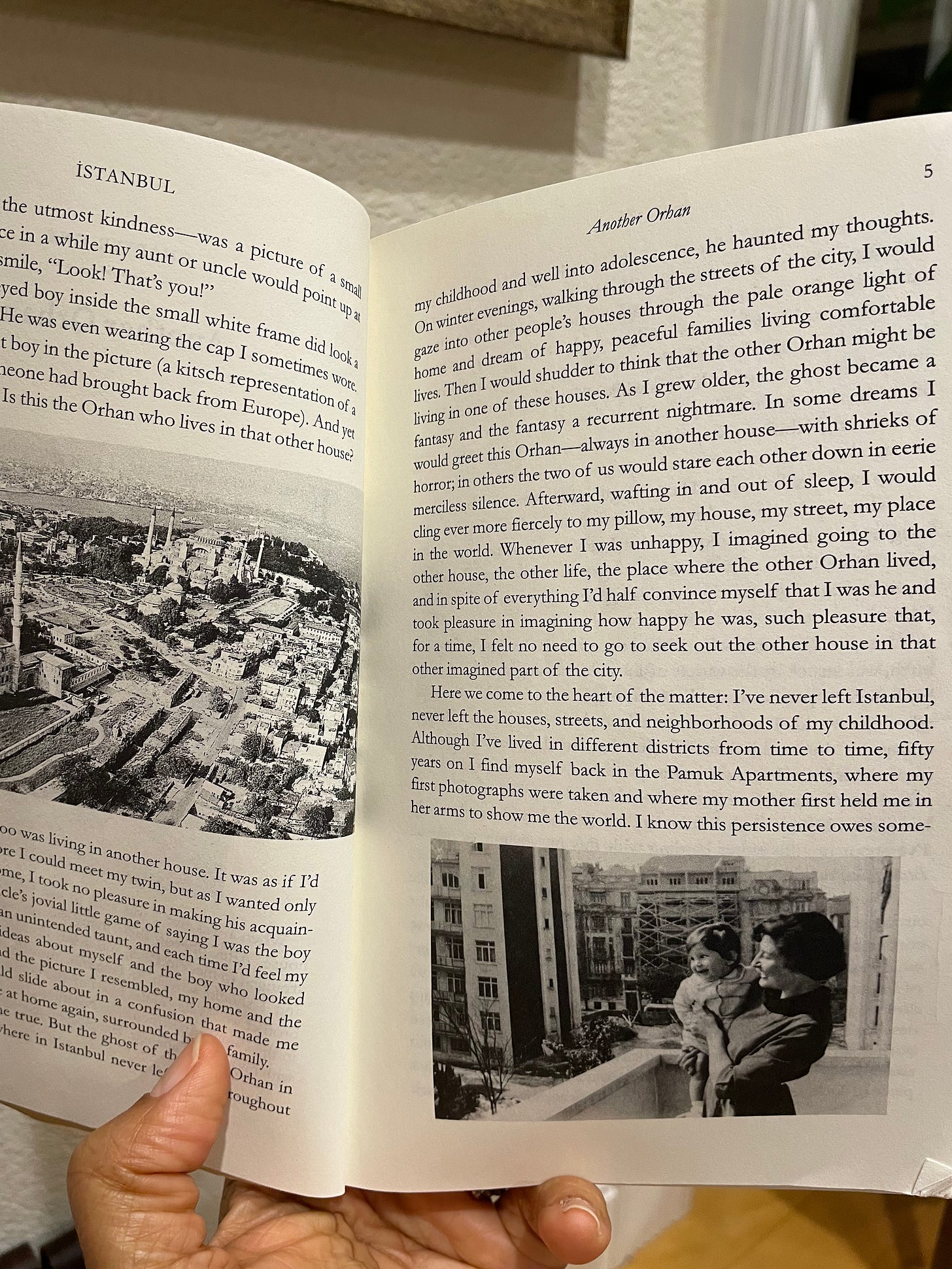

The story of Orhan Pamuk’s evolution from being a child fascinated by words to one who would enchant the world with his words is told in shimmering loopy passages splashed across 37 chapters interspersed with photographs of Istanbul and of the Pamuk family. With no captions whatsoever, each black and white photograph tells a story of its own.

The thoughtful curation of chapters and photos enriches the memoir, gradually leading us to a portrait not just of a crumbling city but also of a morose kid who, his mother hinted, might go on to become a no-good youth. For what else would become of a child from old wealth who had dropped out of architecture college at 21, wasted his years ambling about in the city for hours, cigarette in hand, and resorted to painting canvases while sitting in his parents’ other apartment in the suburb of Cihangir?

Pamuk, it seems, was finding himself for so long that his mother found him exasperating. In the interim years, his elder brother was charting the parent-approved, world-touted path to success—studying, getting good grades, attending college and entering the world of work. While his mother would never fail to remind him that he was teetering on the brink of failure, his father kept talking to him about the promise of another world of limitless possibilities. Pamuk’s father seems absent from his life, yet it seems that in his cameo appearances, he makes a deep impression on him.

“I’d listen to my father’s wise voice telling me how important it was that people followed their own instincts and passions; that actually life was very short; and that also it was a good thing if a person knew what he wanted to do in life—that, in fact, a person who spent his life writing, drawing, and painting could enjoy a deeper, richer life—and as I drank in his words, they would blend in with the things I was seeing.”

As we follow the story, we follow the angst of a listless youth at the cusp of adulthood. His frustration begins to match the pallor of a city that’s forever on the fault line between the east and the west, the sunny and morose, the beautiful and the ugly, and the traditional and the modern. If his own inner life is shaky, so too is their family unit, cleaving ever so slowly with the deepening rifts in their parents’ marriage. It seems to be a slow unraveling, fortunately, thanks to the one source of solace that all Istanbullus (inhabitants of Istanbul) turn to over the course of their lives. Whenever things went awry at home, as Pamuk says, they could always walk along the shores of the Bosphorus in order to heal.

“For me, the thing called family was a group of people who, out of a wish to be loved and feel peaceful, relaxed and secure, agreed to silence, for a while each day, the jinns and devils inside them and act as if they were happy.”

We begin to understand that Istanbul’s inherent melancholy (or “hüzün”) will always be the underlying character of the place. Again and again, readers walk alongside Pamuk, past Byzantine ruins overridden with ivy, past fountains in which the water has long ceased to flow, past abandoned homes that once belonged to someone of consequence. The “hüzün” of Istanbul that has a way of seeping into its people begins, slowly, to drain into our bones even as we behold the grandeur of the Ottoman past.

“To stand before the magnificent iron gates of a grand Yalı bereft of its paint, to notice that sturdiness of another Yalı’s moss-covered walls, to admire the shutters and fine woodwork of a third even more sumptuous Yalı and to contemplate the Judas trees on the hills rising high above it, to pass gardens heavily shaded by evergreens and centuries-old plane trees—even for a child, it was to know that a great civilization had stood here, and, from what they told me, people very much like us had once upon a time led a life extravagantly different from our own—leaving us who followed them feeling the poorer, weaker and more provincial.”

This memoir is specific and its focus is Istanbul. Yet even as we learn about the vanity and pretentiousness of the westernized segment of Turkish society, we see so many cultural similarities to the stories of those who were once colonized.

As the president of the newly formed Turkish Republic at the turn of the 20th century, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk initiated reforms with the aim of building a progressive and secular nation-state. In 1925, Atatürk encouraged the Turks to wear modern European attire abandoning their own sartorial traditions. Turkish life began to change.

Pamuk observes how almost every westernized Turkish home had a piano and a glass display cabinet with all sorts of curios. No one ever played the piano in his home, he writes. “Never having seen them put to any other use, I assumed pianos were stands for exhibiting photographs.” Istanbul is full of comical insights like these and it’s while enjoying those moments that I realized how much every metropolis in India resembles Istanbul.

Unlike Turkey, however, India was colonized by the British Empire; although the English left India in 1947, the white man lives on in spirit inside many Indian homes even today. Indians still take great pride in speaking the English language and quoting literature from England while neglecting their own treasure trove of ancient classical literature. It’s this aspirational quality for everything western that Pamuk mocks while admitting that he and his family were also caught in its throes. The western gaze colored the literature coming out of Turkey, according to Pamuk, and stunted the work of some of the most gifted writers thinking and working in Turkish in the 20th century.

Reading Orhan Pamuk requires patience. He packs in a lot. In order to relish his ideas, his lines must be reread several times. Brilliant as he is, he also tires me a tad by returning to the same idea over the course of the chapters. Having lived with a husband who packs in a lot and is equally adept at repetition, however, I’ve learned, over the years, to tolerate and imbibe as much as I can. The reader who stays with Pamuk all the way through to the end receives a massive literary windfall. As I wrote at the outset, there’s so much to learn from this writer.

I’m in awe of his propensity for self-analysis. I cringed many times at his fearlessness in revealing intimate truths, for showing us—even when we wished to leave the page quietly—the snot, blood, and semen, in some moments, of his tumultuous journey from adolescence to manhood. I’m so glad I stayed. Throughout this terrific tribute to Istanbul, Pamuk’s painter’s eye constantly left me wanting more.

Having said that, I must admit to being incensed whenever he used the word “fat” over and over again, sometimes in the same passage. It’s not simply just inelegant coming from a man with such a nuanced pen. In what otherwise was a brilliant memoir this felt somewhat tone-deaf. His grandmother was fat, he says, and her corpulent self is described at length on page 116; on page 122, we read about a classmate of Pamuk’s who is halfwitted and fat; there is a fat stingy boy on page 127. This question has been debated forever at literary meets: How must memoirists walk the fine line between being brutally honest and being hurtful? It struck me later that Istanbul: Memories and the City was published in 2004, almost two decades before the waves of political correctness began to wash over our world of words, cleansing our language and, some might add, whitewashing the truth.

“At least once in a lifetime, self-reflection leads us to examine the circumstances of our birth. Why were we born in this particular corner of the world, on this particular date? These families into which we were born, these countries and cities to which the lottery of life has assigned us—they expect love from us, and in the end we do love them from the bottom of our hearts; but did we perhaps deserve better?”

For my whole life, Istanbul--and its ghost Constantinople--has been a dream destination. When I go (next year?), Pamuk will be my guide. Before I read Snow, I never knew that there even was such a thing as a door-to-door yogurt salesman. And I came to care deeply about one! I can’t imagine what depths of feeling and understanding will come when Pamuk shows me his city! Though I’ve learned my lesson: I won’t judge anyone by body size, I promise!

lovely . Turkey and Istanbul IS A GREAT FASCINATION FOR ME. I DEVOUR TURKISH MOVIES AND SERIALS. Have started learning the language too !

Im going to definitely read this.