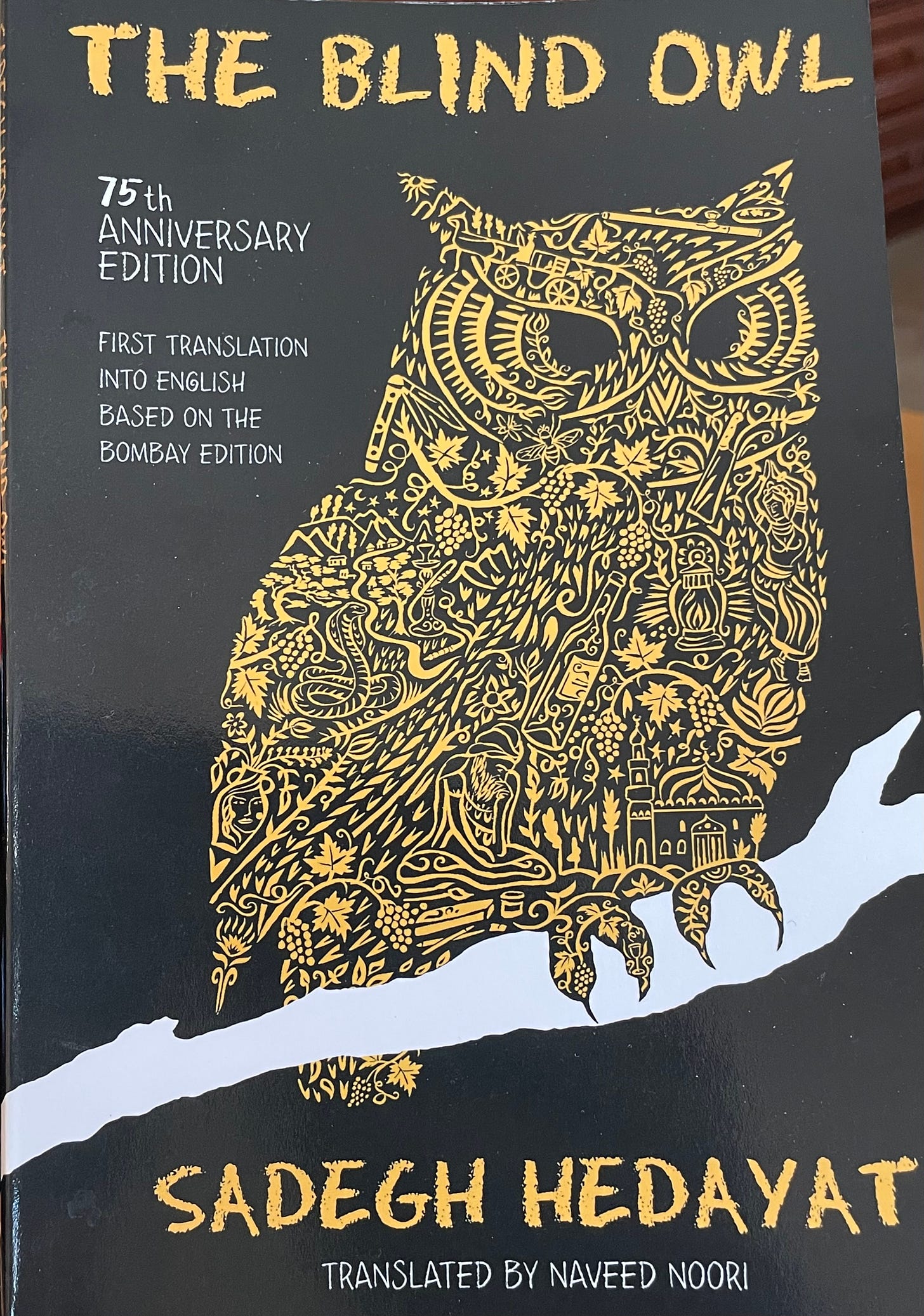

BLIND TO THE LIGHT OF A BOOK?

The Blind Owl by Sadegh Hedayat was as oppressive as the California heat wave.

After last week’s read about The Plague, this week I picked up a book that discombobulated me so completely that I would have put it away had it not been only 75 pages in all. If Albert Camus’ work rang as clear as a bell even in the thick of its most abstract pondering, Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl was inscrutable from start to finish. It was unfathomable, unpleasant and unending.

The Blind Owl was composed in Iran during the latter years of the oppressive reign of Reza Shah and first published in 1936 in Bombay, India, where Sadegh Hedayat was studying. It apparently became a classic of Persian literature although, as Hedayat notes in his book: “The printing and sale [of this work] in Iran is forbidden.” The government banned it because of its tendency to induce teenage suicide. As the narrator descends into an opium-fueled abyss, it’s impossible to not wonder how much of his story is couched in reality.

I expect any book I read to inform, entertain, illuminate and, hopefully, move me in some way. The Blind Owl did none of these for me. The prose in this surrealist novella was magnetic, and the imagery stunning in some parts. I loved Hedayat’s description of a row of dark shadowy trees along a road in the night: “The trees, intertwined with their crooked and twisted branches, were holding hands, as if they were afraid of stumbling and falling in the dark.”

In what I understood to be the narrator’s brief moments of lucidity, his commentary on life was thought-provoking. Morbid as many passages were (on the subject of dying and death), I found some worthy of introspection. The narrator ruminates on a state when someone is rent apart from the visible world, and alludes to “the sound of Death”.

Has such an occurrence not happened for everyone whereby suddenly and without reason they go into thought and so immersed are they in thought that they become unaware of their surroundings and time, and forget what it was they were thinking of?

Likewise, the opening line of the book drew me in right away.

In life there are wounds that, like leprosy, silently scrape at and consume the soul, in solitude—.

In his preface, the translator, Naveed Noori, discusses how two other translators handled the same opening line.

D. P. Costello: “There are sores which slowly erode the mind in solitude like a kind of canker.”

Iraj Bashiri: “In life there are certain sores that, like a canker, gnaw at the soul in solitude and diminish it.”

In the long preface that I found more interesting than the book itself, Noori delves into the challenges in translation and explains the notion of domestication versus foreignization. “Domestication occurs when fluency is strived for at all costs, and the culture, words, and even meaning of the text are made to conform to the target language. Foreignization is the opposite, where an effort is made to preserve the source language and culture by use of language or techniques that may be unfamiliar to the reader.” Noori points out how while Costello’s translation is a smooth read, he misses some of the nuances in the original and goes on to demonstrate his own choices in translating some of the passages.

The Blind Owl is a dense, dark work that obviously expects a reader to have a deeper understanding of the Persian culture and history. A passage in the preface seemed to lend meaning to the work and made me realize how many holes in understanding I had. This extract from the preface suggests that The Blind Owl may have been Hedayat’s manifesto. This made complete sense, given another poignant fact about the author’s state of mind and the recurrent themes in his body of work. At the age of 48, Hedayat gassed himself to death in his apartment in Paris after leaving money for his burial.

You may understand why I need to lift myself out of the ponderousness of this week, especially when it has been hellish here in Northern California as the heat wave set a new record. Try reading The Blind Owl in 109 degree heat. At least the narrator in the story was on an opium high.

I admire you for ploughing through to the end! I guess something is clearly lost in translation here, both linguistically and culturally, since this book is a classic in Iran (and banned, too!).

You really know how to sell a read, Kalpana: “unfathomable, unpleasant and unending.” Reminds me of Thomas Hobbes’s characterization of life as “nasty, brutish, and short.” (Except for the “short” part.) I quit reading “Under the Volcano” because ...well...why bother reading about a drunk? Maybe the same literary exclusion applies to opium addicts. Love that cover illustration though!