A COMET HITS THE WORLD OF ENGLISH

A curated collection of short stories by the late Gujarati writer Dhumketu was recently published in the United States. I've been awed by these stories and his body of work.

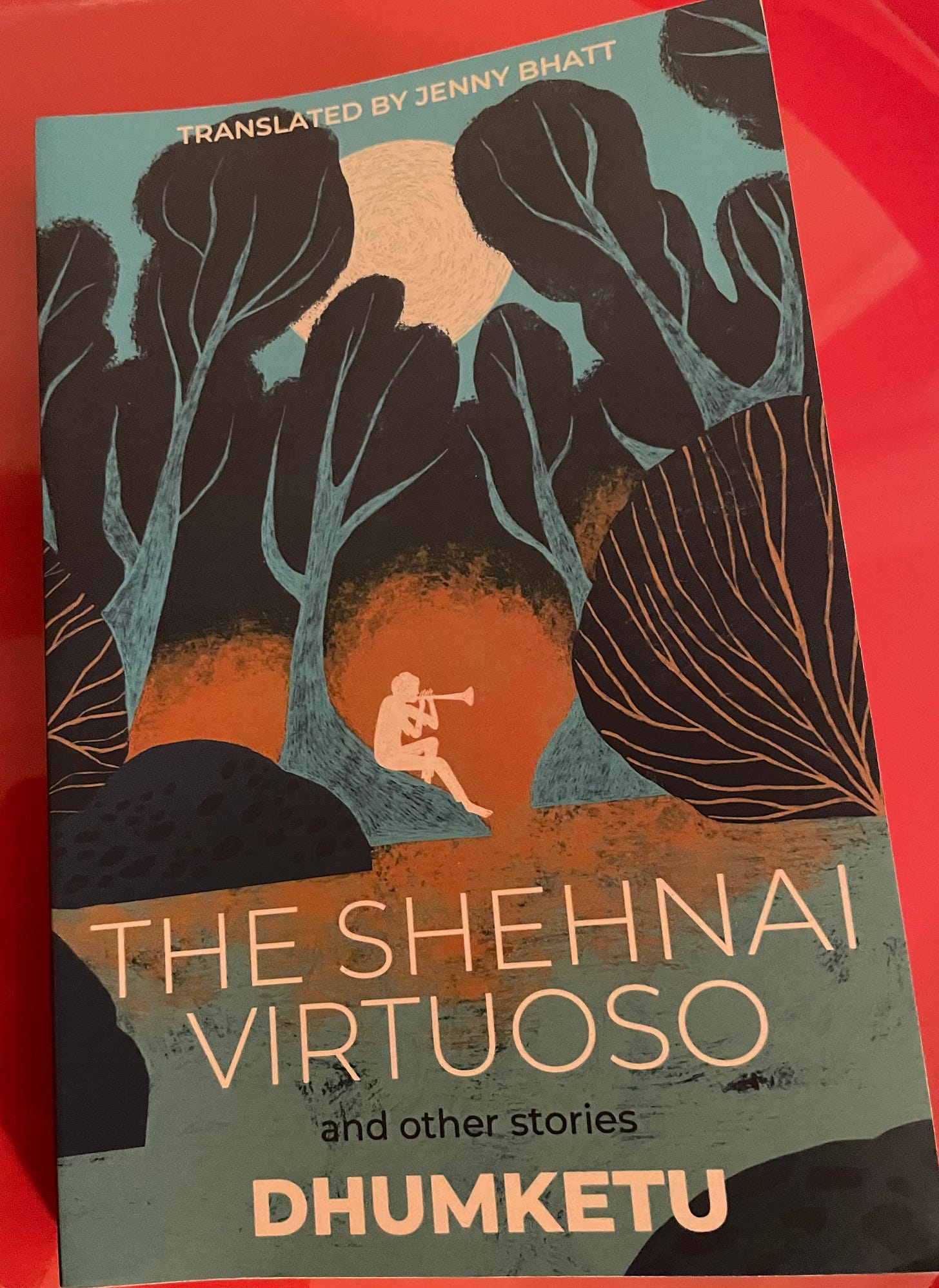

I attended the South Asian Literature and Art Festival (SALA) last weekend in Saratoga. After sitting in on the discussion on translation, I rushed over to the bookstore on the premises to buy The Shehnai Virtuoso. The cover is evocative of India’s glorious artistic heritage and its very first story, The Postmaster, sets the tone for the lingering melancholy of the stories I read in the book.

Considered one of the pioneers of the Gujarati short story form, Dhumketu wrote more than 500 short stories. His work in this genre spans across twenty-four volumes. Born into the name Gaurishankar Govardhanram Joshi, he mostly published under the pseudonym of Dhumketu which means “comet”. In this article for lithub, Jenny Bhatt, the curator and translator of this collection, says Dhumketu also published twenty-nine historical novels, seven social novels, numerous plays, travelogues, essays, literary criticism, and memoirs. During the panel at the SALA festival, Bhatt mentioned Dhumketu’s myriad influences—Tolstoy, Gorky, Chekhov and Maupassant—and pointed out that Dhumketu also worked on translations of writers and poets such as Kahlil Gibran, Rabindranath Tagore, and others. I was awed by the depth and breadth of one man’s work. It was a body of work that had been inaccessible to those of us who only inhaled the world of English.

During our six-month stint in Singapore, I worked on a post on how the Tamil language had flourished in this country because of Singapore’s thoughtful policies both in education and nation-building. While writing that article, I discovered how Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and Chekhov and other Russian writers had been translated into Tamil. I was fascinated by lectures on Russian literature by illustrious Tamil writers in Chennai. I stalked their YouTube videos. It was a world I did not even know existed.

Too many of us believe that all scholarship rests in the world of English. Writers like Dhumketu were virtuosos and it’s unfortunate that the world of English gets to read his stories only now, over 60 years after his passing. Those of us who transact in literature in the English language suffer from delusions of grandeur, it seems, but the grandest irony is that evangelists such as I must process and convey all these thoughts, too, in the English language.

Of all the stories I read in The Shehnai Virtuoso, The Happy Delusion was probably my personal favorite. I empathized with the predicament of the young man in the story. Early on we meet Manmohan, a young man who has the courage of conviction that his life’s mission is to create his literary magazine. He believes in its worth and his quality of work even thought no one else believes in it. Against the advice of his mother and other knowledgeable people, he even enters into debt while continuing to publish his magazine year after year. Decades later, when the narrator visits Manmohan’s humble home, he’s taken aback. He feels sorry for the young man he once knew but realizes that Manmohan, poor as he is, seems to be at peace with himself. He seems happy.

The narrator of the story, the man who passes judgement on Manmohan’s work, represents the voice of society. I wondered why he too quashed Manmohan’s dreams early on. Was he the best judge on the quality of Manmohan’s work? Why was he irked by Manmohan’s self-confidence? The narrator revises his judgement upon his meeting years later. He is ambivalent now.

“What was the accomplishment of this man’s lifetime of labor? Nothing at all, was the answer. But wasn’t his hard work the highest possible degree of his achievement?”

Dhumketu ends this story with a question on the nature of work itself, saying that “those who build their own little temples, the small people with such happy delusions—are they not really greater than those who make grand, propaganda-driven proclamations about seeking the truth? Who can say?”

In every story that I read from this collection, there were lines that zeroed in on a truth about the human condition that I had never seen quite so clearly before, little points of light that were reminiscent of runway lights on an air field.

In a story called The Rebirth of Poetry, Dhumketu wonders about beauty and variety and tells us about this fictitious place where beauty has been completely eradicated in order to build a more just society.

Beauty makes the world crazy and poets have written in praise of it. Given this, to ensure that the germ of such a grievous disease does not enter any person, surgery was done to give all men and women identical faces.”

In this place, only “wholly healthy women and men were allowed physical relations and offspring from any other unions were killed immediately.” Soon, however, things fall apart. When everyone looks like the other, when all the differences that make each of us unique are nonexistent, when each of us does not count for something, when all the desire for being different is met with disdain and “surgery”, have we not eliminated the purpose and significance of life? By the time we arrive at the end of this explosive work, we know that it is uniqueness and variety that lends meaning to our days.

Jenny Bhatt’s translation makes the process of reading effortless. It’s just a little after Diwali, after all, and hence I can only compare my reading journey to the satisfaction of eating an almond halwa prepared with attention to detail. I consumed the stories with a sense of wonderment, skipping around as I wished. I left some for another reading session, just as one saves the last spoonfuls of halwa for another evening. For this collection, Jenny Bhatt selected at least one significant story from each of the 24 volumes while remembering to include the most anthologized story titled The Post Office.

Each tale by this transcendent genius, unfortunately, is also a mini heartbreak in capsule form. In one case, a child, who is being told a story by his parent, longs to know the whole story but the parent, a busy lawyer in the village, is always distracted. On The Banks Of The Sarayu is so precious a story that I believe it has the power to be one of the world’s great tales in children’s fiction. A parent (who is always distracted) and a child (who needs to know the story now!) must read this together.

Through the trajectory of our lives, one thing is true, that the deepest melancholy of our lives feels impossible to put into words. It’s inside of us, like diminutive shards of broken glass that may surface here and there as unexpectedly as that sudden splinter on our finger. These stories by Dhumketu capture precisely those aches. They memorialize those pangs.

If you liked reading LETTERS FROM EVERYWHERE, don’t also forget to check out SO MUCH TO SAY, the newsletter that arrives in your inbox on Wednesdays.