TAMIL IN SINGAPORE

My six-month stay in Singapore has given me a ringside view of the life of my mother tongue, Tamil, far away from India.

When someone wonders about where I feel most at home, I say, without a moment’s hesitation, that it is the San Francisco Bay Area. It’s a place that burnishes me into my truest self.

In America, I can speak, rant—chew gum—pontificate, crib and air my opinion about everything under the sun, including the government and its institutions. For a writer, this freedom is reassuring. It is a privilege, too. Yet, even as I acknowledge that, I will admit that something is missing in California for folks like me on permanent exile from our Indian shores. My public and personal worlds do not collide. In Singapore, on the contrary, I’ve experienced the meld of the personal and the public. Those moments have taken me by total surprise.

I experienced one such moment two weeks ago as I was leaving Chinatown to catch a bus back home. I happened to step into Temple Road just before noon, without realizing that I had been walking along the periphery of the country’s oldest Hindu temple built in 1827. I stopped in my tracks when the strains of a familiar Tamil song played perfectly on the nadhaswaram tumbled over the sand-colored walls of the temple. Ears burning, eyes smarting, I decided to enter Sri Mariamman Temple.

Inside, the daily noon prayer ceremony was in full swing in the presence of a handful of devotees. Stunned by my timing, I watched on, swaying to the perfect rendition of a legendary song of Tamil cinema—Singara Velane Deva—a classic that I associate with my hometown of Chennai and every village in Tamil Nadu. This unexpected experience evoked Tamil life and culture so completely that I realized, in that moment, just how much I missed such manifestation of cultural serendipity in the United States. In Singapore, the Tamil culture from which the Tamil language draws so much of its energy feels like an integral aspect of daily local life.

Now that I’ve been living in such a place, I will admit that it’s equally unsettling as it’s exciting to hear Tamil almost on a daily basis in public. Audio announcements on trains and buses as well as display boards in public are in all four languages: English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil. I find my eyes searching for Tamil script adorning signs—by the riverfront, in museums, on all the Covid-19 vaccination posters, and on traffic signs. I often hear my mother tongue spoken by folks who pass me by as they chat into their phone.

Assaulted by this ubiquity of Tamil, I also chafe at the nonchalance among members of the public who’ve been inured to this over generations. I wonder about how much they know. How many non-Tamil Singaporeans actually know that Tamil is one of the oldest languages in the world or that its deep literary tradition spans over two thousand years, or that to understand Tamil and the history of Tamil literature is to appreciate the ancient history of Tamil Nadu and the social, economical, political and cultural upheavals of the Indian subcontinent itself?

In Singapore, Tamil is developing its own tang. Today, most Indians in Singapore are locally born second, third, fourth or even fifth generation descendants of immigrant forefathers. In addition, a good number of them are recent immigrants from the Indian subcontinent. Since the country became independent, language and the teaching (and the grading) of it has preoccupied those who design the education curriculum. It has been a fraught subject, naturally. You see, language is at once personal as it is public.

Singapore decided early on that every student in the Singapore school system must be bilingual. Bilingualism has been the cornerstone of Singapore’s language policy since the People’s Action Party (PAP) came to power in 1959 when self-government was granted. While English was slated to become Singapore’s working language and the language of government and commerce, the mother tongue would serve to strengthen an individual’s values, heritage and sense of cultural belonging. The policy entails an emphasis on using English and the mother tongue languages, particularly those of the three main ethnic groups: Mandarin for the Chinese, Malay for the Malay community and Tamil for the Indians. Note that Tamil Indians make up only a third of the Indian community. The demographics of Indians in Singapore has also steadily changed as Indians from many different parts of India converged here after Singapore became a developed nation. See how this gets complicated?

As a second generation 27-year-old Tamil Singaporean, Shyama Sadashiv saw the challenges of choosing “a second language” up close; several friends of hers chose to learn Tamil. Unlike Shyama, however, their exposure to Tamil in their home was almost non-existent. Shyama speaks Tamil effortlessly but she attributes it also to the hired help at home over an eight-year period. The help did not speak English. When Shyama returned home from school, she entered a world where Tamil was the only medium of communication. Shyama believes the policy for mother tongue learning was a great concept, after all. “I think it’s brilliant,” she says. “Language is the key to culture. You can always be Indian or Tamil but until you can speak the language you are, to some degree, locked out.” While not every Indian friend she studied with possessed her advantage while navigating the school system, the language policy definitely fostered a sense of identity and belonging for those who learned Tamil.

“Tamil class is an iconic thing in the context of the Indian Singaporean identity,” Shyama says. The whole ecosystem of Tamil involved many things: The “inside” jokes; discussions of articles from Tamil Murasu newspaper; the Tamil competitions that many schools participated in; the poetry contests; the skits based on Tamil culture; and, not the least of it, an 8.30 PM “word for the day” announced on Tamil Seithi television program. Naturally, television shows also contributed to the cultural zeitgeist. The TV shows on Vasantham channel (a dedicated Tamil channel after 2008) often gave students a lot to talk about. Shyama says that whether or not everyone at school had watched Vettai (Hunt), a Singapore Tamil drama series, they had to know the details simply in order to belong to their cliques. Shyama believes that Tamil Indian Singaporean students have created an identity around being Tamil in Singapore because of Singapore’s mother tongue language policy. In universities, students seek to create spaces where they can bond, long after they leave for college, through associations that are natural extensions of the spaces that nurtured both the students’ Indian—and, somewhat often, Tamil—identity. Apparently, Singlish (Singapore’s colloquial English) has found a way into Tamil, too, as in the way someone might say ‘Yenna-aa lah”. Sentences in Singlish are generously peppered with “lah” and a Singaporean friend born in Malaysia coached me once on the manner of usage.

The Tamil curriculum in schools has now evolved to such an extent that there’s now an effort to also be self-sufficient in Tamil pedagogy and to build and print local texts in the teaching of the Tamil language when, in the past, it looked to Tamil Nadu for guidance. As the demographics changed among Indians, the ministry of education began accommodating Indian children who wished to learn another Indian regional language in place of Tamil. Despite the changing Indian populace, Tamil is the dominant Indian language in the nation and the goal of Tamil education is to produce more cultural elites who are schooled well in Tamil and to ensure that Tamil thrives in Singapore. Several decades of focused Tamil education certainly has made it an attainable dream, I realized, when I heard the panel of speakers at the Singapore Writers Festival in 2020.

One of them, Bharathi Moorthiappan, pursues her passion for Tamil through her education company, EduClassic, that she launched in 2012. Her goal is to encourage reading among her students and to instill a love for language and literature through Tamil programs with plays, poetry workshops, speeches, and debates. A Tamil teacher with a postgraduate degree in Tamil, Bharathi notices how many of these students read and write at a high level whether or not they are born into Tamil households. During the course of an academic year, Bharathi conducts about forty workshops in Tamil education for students in schools across the nation.

I’ve been awed by her deep interest in Tamil literature (generated in Singapore and in India) and her ability to tell me the stories of the myriad Tamil writers and their craft. Her dexterity and drive in conquering the world of English using Google Translate and Google Keep has got me thinking; shouldn’t I be doing the same to improve my Tamil and my French?

If Bharathi’s energy inspires me, I’ve also been envious of Harini V’s melliflous Tamil and English. This 25-year-old began writing poetry in her early teens. Her fluency in Tamil on the panel caught my attention, prompting me to find out a little more about her lineage. A fourth generation Singaporean Indian, Harini’s great grandfather, B. Govindasamy Chettiar, arrived in 1905 from South India and went on to become a supplier of stevedores, lightermen, wharf workers, lascars and dockyard workers to the Singapore Harbour Board. Harini says she won’t flatter herself by saying she is that rare young poet and writer who straddles several worlds. Pointing to an award-winning writer Sithuraj Ponraj, a polyglot who writes in Tamil and in Spanish, she says there are several like him who consistently persevere at the craft.

For Harini, poetry is therapeutic, especially in these dark times. “When it comes to writing poetry, I started in Tamil first because the language lends itself very easily to writing in the poetic form.” Her influences were Tamil songs from the silver screen. In the texture and wisdom of her words I hear the echo of old familiar melodies and I share here a delightful presentation about her first dream.

In Singapore, thoughtful practitioners of the language—at the level of expertise that Tamil demands, especially given the maturity of its canon—may not be too many. “But even if it’s just a handful of them, it’s wonderful,” Bharathi Moorthiappan says as she watches the work of young Singaporeans like Harini V, Ayilisha Manthira and Ashwinii Selvaraj. “I see ambition in them.” Harini hopes to work on a book-length project that straddles the world of both English and Tamil. She certainly has many awardwinning mentors who were born and raised in this region.

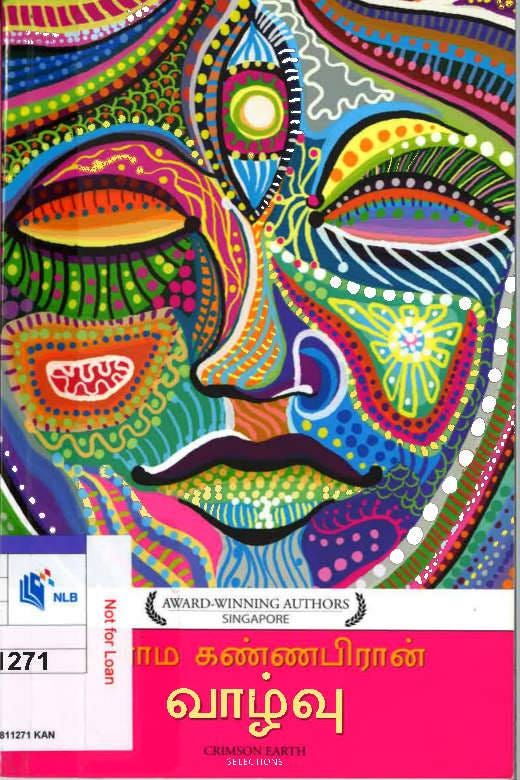

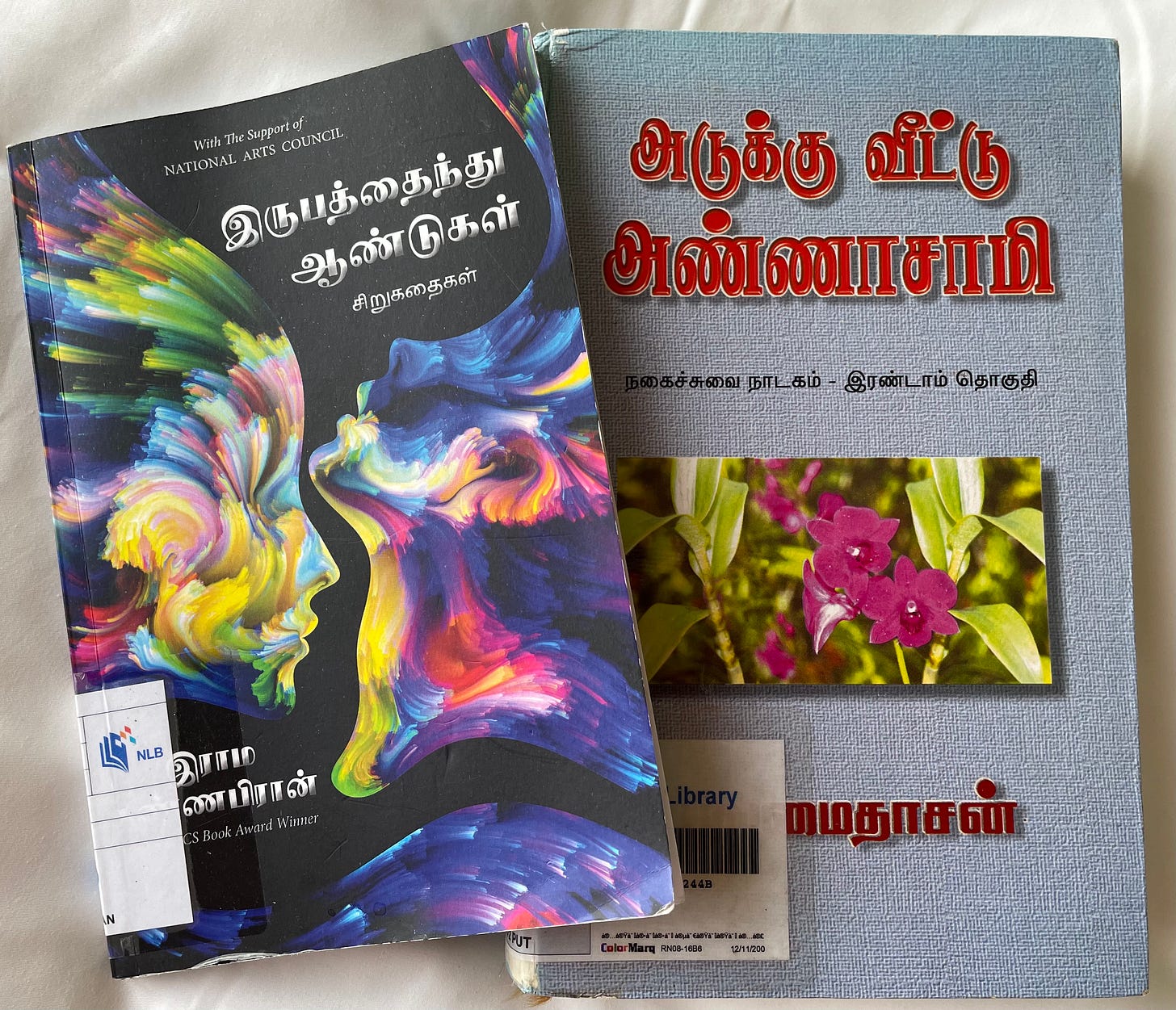

Many of the top Singaporean writers in Tamil show an impressive body of work with creations for theater, radio, television and print. While reading a short story collection, Irupathainthu Aandukal, (Twenty-Five Years) by Rama Kannabiran, a celebrated short-story writer and novelist, I found myself drawn to his descriptions of old Singapore life and social mores after the country’s struggle for self-government in the fifties. I hope to read the stories of P. Krishnan (Puthumaithasan) whose play became a popular radio series in 1969. Adukku Veetu Annasamy captures the lives of Singaporeans in the sixties and seventies after two families moved from their huts in the village to make a new life as tenants in flats built by Singapore’s Housing Development Board. I’ve now discovered a rich trove of Tamil literature, both fiction and nonfiction, in the city’s libraries and I’ve been impressed by the dedication to the cause of all four languages in the public library system.

As for my own journey with my mother tongue, despite my familiarity with casual spoken Tamil, a literary Tamil still eludes me. My own knowledge of Tamil is spotty; as an eleven-year-old I moved to live in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania for six years, where my father began work as an accountant. Those six formative years in Africa would inform my life in countless ways and pack in French into the gap left by Tamil. Here in Singapore, I’m discovering that I’ve immersed myself for too long in the world of English, oblivious to how a language encapsulates within it an ecosphere—of thought, literature, art, culture and being. The language of the colonizer has thus led me away, both consciously and unconsciously, from the world I had once inherited and the many worlds within it. Thanks to Bharathi, I’ve begun experiencing Russian literature through the minds of two brilliant Tamil writers in India, B. Jeyamohan and S. Ramakrishnan (SRa). I’ve been listening to their thoughts, in Tamil, on the timelessness of great writing. “My Dear Chekhov”, a short film in Tamil scripted by SRa, captures the passion I saw in his speeches on Dostoyevsky and Chekhov. I’m growing my Tamil vocabulary. I know now that Singapore, even though I may never call it home, has opened a door beyond which a million places, characters, attitudes and secrets are waiting to be discovered.

Well written 👏🏽. Thank you. As a Tamilian who grew up in Bombay or Mumbai as it is known now, we spoke Tamil at home, but never exposed outside. Imagine our surprise as newly weds, living in Singapore, we experienced the same feeling you express so well in your article. My wife grew up in Chennai and is fluent in writing and speaking and reading Tamil and I, who could only speak the language and read very slowly, experienced joy, which I had not even experienced, even within India.

Raghu Raghuraman

Great write up! Felt so nostalgic! Makes me want to be in chennai right now!