WHILE CROSSING THE MANGROVE

In this fictional Guadeloupean village of Rivière au Sel, a foreigner has been found dead. The late Maryse Conde peels the layers to resolve the mystery and spins a lush, lyrical tale.

I first happened upon the work of the late Maryse Condé when I was looking at the Booker prizes last year. Condé was twice shortlisted for the International Booker Prize, first for her body of work in 2015; then, in 2023, her novel The Gospel According to the New World was shortlisted for the prize. While I intended to read the work last year, I ended up reading and writing about the Bulgarian work called Time Shelter which ultimately went on to win the prize.

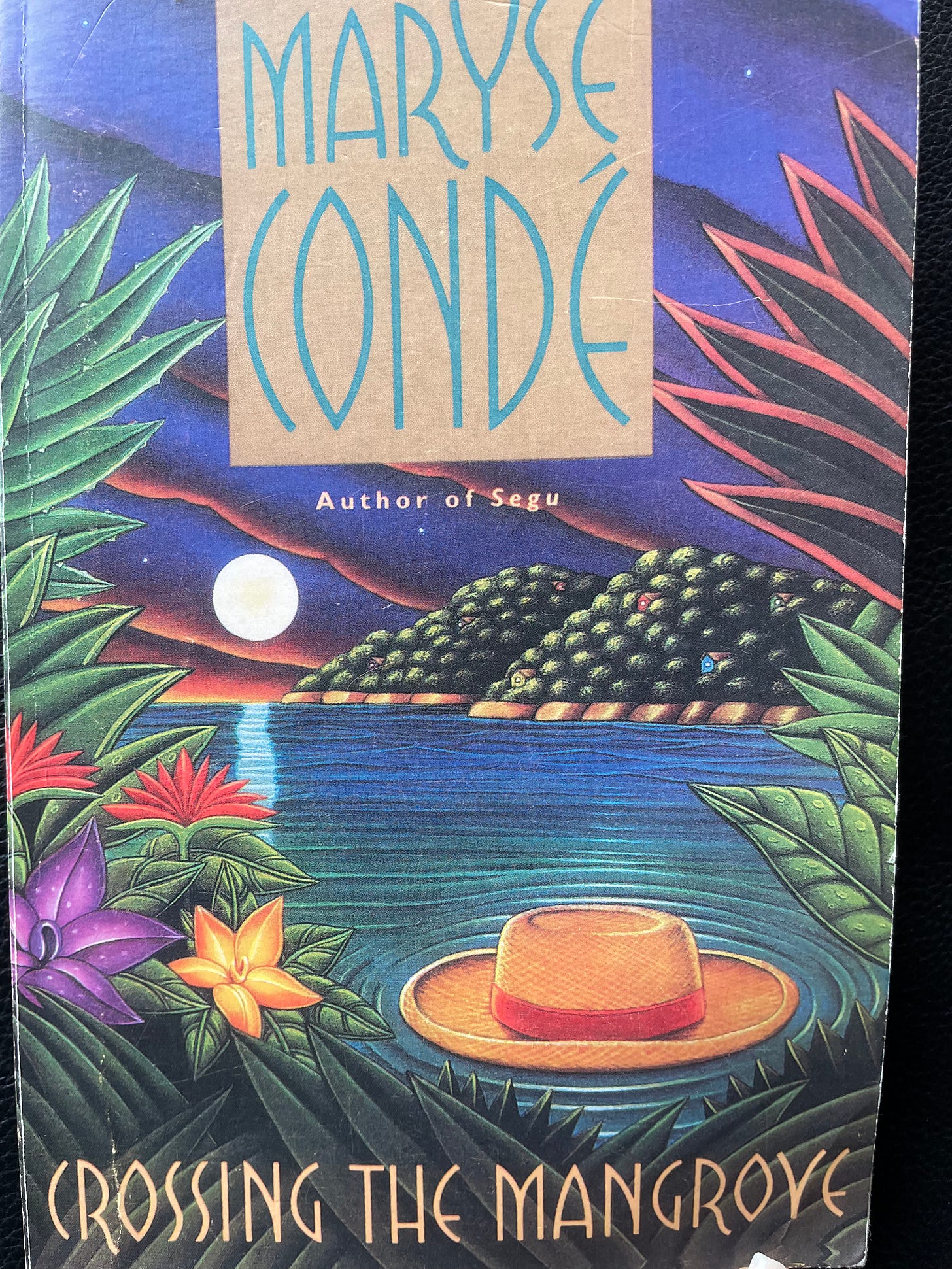

I almost never judge a book by its cover but I’m afraid I actually bought Crossing The Mangrove for its cover when I was shopping for books in Brooklyn. Having now read the book, however, I must say that I actually stayed back for the beauty and magic of her prose. Literally every page from this vibrant work is quotable. I shall begin with lines that will remain with me.

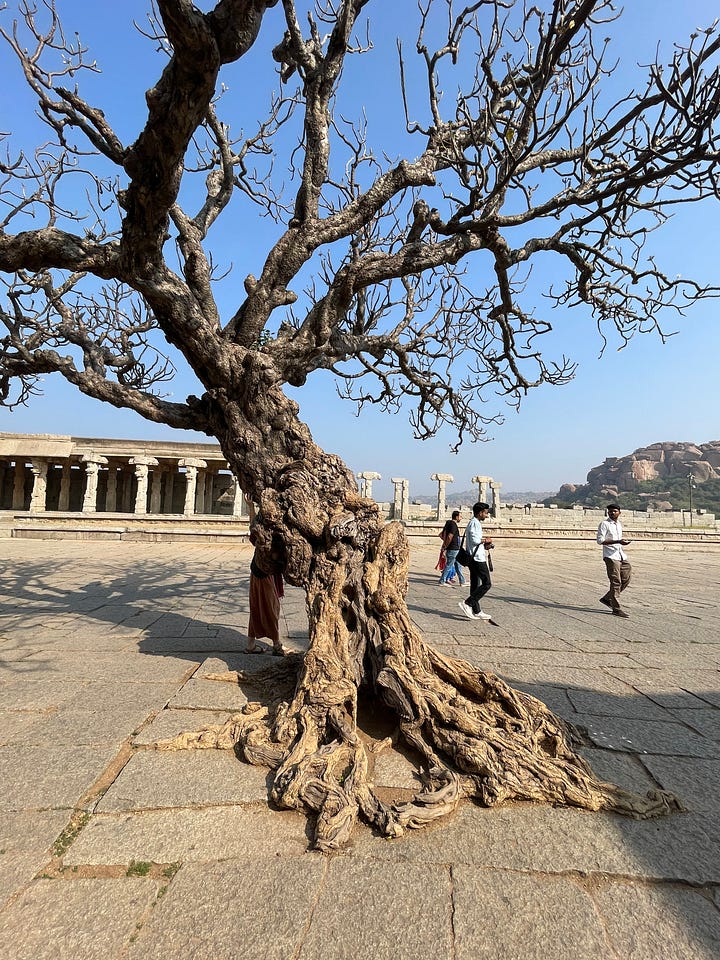

Life’s problems are like trees. We see the trunk, we see the branches and the leaves. But we can’t see the roots, hidden deep down under the ground. And yet it is their shape and nature and how far they dig into the slimy humus to search for water that we need to know. Then perhaps we would understand.

Tell me which of us won’t respond, viscerally almost, to the lines above? Perhaps these lines also spoke to me because I’ve found myself forever attracted to trees with their gnarly trunks and roots. I take pictures of them wherever I go. On my recent travels through the ruins of Hampi in India’s Karnataka, I was drawn to one lone frangipani tree that seemed to have survived the devastation of Hampi in 1526, its warped and sinuous trunk making me wonder how it might actually appear underneath the stone. The tree was leafless in this spartan landscape and, yet, up in the tree were three parrots tweeting and leading their daily lives as if their abode was both luxuriant and indestructible. The setting of this French book is many worlds away from Hampi.

Guadeloupe is a lush island group in the southern Caribbean Sea, a French overseas region whose layout physically resembles the lines of a butterfly; its two largest islands are separated by the Salée River. On every page of her work, Conde invokes the breathtaking beauty of these islands with their long beaches, thinning sugarcane fields, dense forests, gullies, swamps and volcanic landscape. Several characters in the work are intrinsically linked to their land and the passages describing these are simply stunning.

We grew up like two savages. We know each other’s secrets. But I have never taken him down to the Gully. That place is mine. It’s my realm and my refuge.

Aristide says he could never live far from the mountains. Every morning he delves deep into their belly and returns with his backpack full of yellow-footed thrushes, black woodpeckers, partridges and woodpigeons that he has limed among the ferns and that he keeps in bamboo cages at the bottom of the nurseries. His realm is his greenhouse of orchids. Those people who say his heart is as hard as stone don’t know him.

Crossing The Mangrove takes a rather unique approach to the narrative. As the story opens, a man called Francis Sancher is found dead. Little by little, we learn more about the death of this foreigner on the island. He’s a handsome hunk of a man, loved by few and despised by most for reasons that often don’t make sense. He’s found face down in the mud on a path outside Rivière au Sel, a small village in Guadeloupe. Sancher, it turns out, is an inscrutable and melancholy man who maintains that an unnatural death awaits him.

As we begin to see preparations for Sancher’s wake, we learn a little more about Sancher with every story told by yet another person from Riviere au Sel. By the time we reach the end of the story, we’ve learned few details about the actual mystery of his death. Instead, we’ve gleaned so much about the people of this country. We’re privy to their biases and their insecurities, and we learn how the roots of colonialism run far, wide and deep.

Like all those who lived in Rivière au Sel, Carmelien knew and respected the Lameaulnes, because they were almost white, because they lived in a house with “Private” written on the gate from which you could see nothing except for a brick-red roof between the fronds of the cabbage palms if you perched on the branches of a mango tree on the edge of the road; because they had so much money, said Sylvestre, who was a connoisseur of well-stocked bank accounts, they could have bought the whole of La Pointe if they wanted to.

Condé’s greatest gift, I thought, as I read lines like those above, is her uncanny skill in painting the character and the attitude of a place with deft and sinuous strokes. We begin to see how the minds of the people in Riviere au Sel are enslaved, long after the people have shaken off the chains wielded by the white explorer. Centuries after their liberation, the people, depending on their color and profession, wield the baton or flinch when they see someone whose skin color is at odds with their own. There are also the political leanings of the locals that reflect the state of the world beyond the Caribbean Sea; naturally, communist predilections raise eyebrows in this place. The late Sancher’s own mystique partly rests in his connection with Cuba.

As the villagers arrive to pay their respects out of sheer curiosity (or out of genuine sorrow), we hear their words and we receive yet another piece of the mystery behind Sancher’s life and death. By and by, we learn the reasons he seems to shun all attachment even though he has led an impassioned life helping people as a doctor in many countries in Africa and in Cuba. Even though he has loved many women, he remains mysteriously unattached. We learn the reason for this life decision by the time the story ends even though we really do not get to know more about the mysteries surrounding the end of his life. We do begin to see the light, however: How can he bring a child into the world when generations of men in his family seem cursed?

I think I’ve never been closer to Francis Sancher than tonight, now that he has nothing left to say, now that he has gone and will never come back. Our ancestors used to say that death is nothing but a bridge between humans, a footbridge that brings them closer together on which they can meet halfway to whisper things they never dared talked about.

Crossing the Mangrove is undoubtedly a paean to the beauty of island life and a reminder that underneath the dazzling beauty of sun, sand, mountain and sea lie gut-wrenching stories of human lives that must always be told. Maryse Conde leads us through a uniquely Guadeloupean wake for Francis Sancher using language that’s at once personal and universal.

The translator’s preface (Richard Wilcox happens to be the writer’s husband) tells us how he, the translator, went about creating a language that’s at once intimate and accessible: “How was I going to translate those distortions of the French language that Creole is so fond of making and at the same time poke fun at standard, academic French?” Wilcox apparently found his solution in works by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. “I found that tone and register of voice, those trifling details with universal significance, the way the colors of Nature interweave in personal lives and the way the reader is made to look at the horizon and then back again to him or herself. I found all this in Virginia Woolf, and in particular in her novel To the Lighthouse.”