WHAT IS A MOTHER?

In this terrific novel, I recognized all mothers. Mothers are providers. Mothers are also manipulators of those they care for.

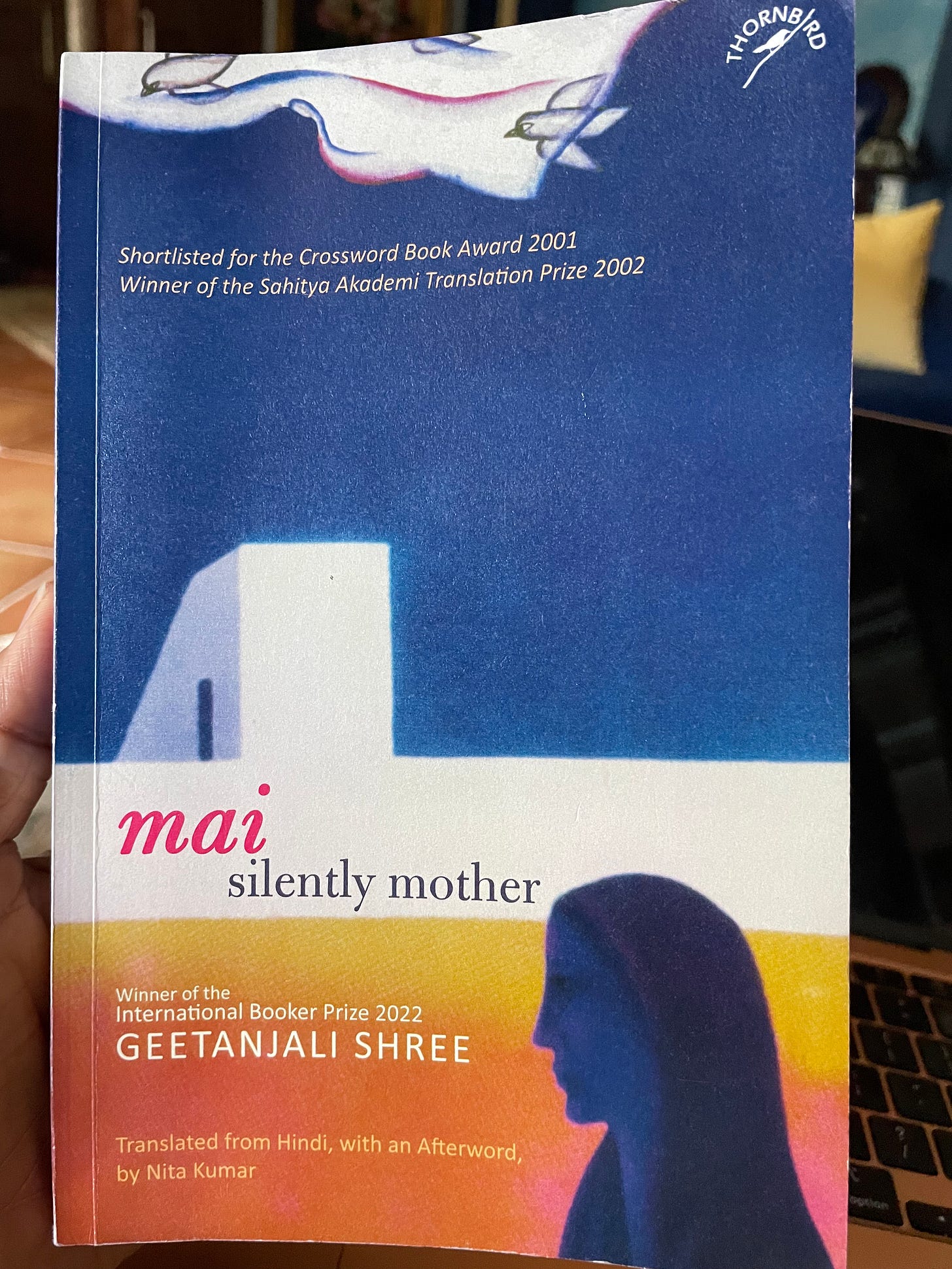

It’s not very often that I come across a book whose subject matter is so universal that the work deserves to be translated into every language in the world. Originally published in Hindi, Mai Silently Mother, by Geetanjali Shree, was translated by Nita Kumar in 2017 and published by Niyogi Books. Kumar’s translation won the Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize; Kumar’s afterword is a great gift for readers on how to think critically about a book. Mai Silently Mother has been translated into several languages, including French, German, Serbian and Korean. Now that Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand has won the International Booker in 2022, I hope Mai will be translated into many other tongues as well.

Mai Silently Mother dropped into my life in an unexpected way a couple of weeks ago. I wasn’t looking for it; it was simply one of just three or four books in translation languishing at a Chennai bookstore called Words & Worths. Now this is not really a bookstore. There are neither good enough books nor worthy enough wristwatches in this bric-a-brac store. I’ve discovered over the years that I cannot discount any book shelf whatsoever. Thus here was this little dynamite of a novel in 224 pages that I managed to read over two days on a road trip through the Mangalore region of India.

Mai Silently Mother is about three generations of women and the men around them. Its subject, of course, is eternally fascinating: Mother. I pounced upon it and realized, yet again, that it felt like serendipity. My husband and I had just spent a week with my mother-in-law and father-in-law in their home in India’s Vellore. When I left their home after a week, I ended up asking myself many questions about womanhood and motherhood.

My in-laws are now 91 and 85 and I’ve felt frustrated that as my husband’s parents aged, my mother-in-law’s work load had increased even more. My mother-in-law has taken on more physical and mental burdens even as my father-in-law has begun offloading his own. She has always been the domestic goddess who kept the home in balance. Her presence lends meaning and value to the house and has made it a home for all of us, whether we were away from her home or living in it temporarily. She continues to be our provider, the one who asks after our health and always wonders what she could make for us to take back home to our own kitchen in the United States. Yet as I’ve watched her give so much to all of us, I’ve wondered if this were not also a choice.

Geetanjali Shree’s novel asks questions precisely about such things as the nature of our mothers and the notion of motherhood itself. We look upon a mother as a passive provider who never changes the way she works. Mothers provide to others until their dying day. Mothers embody sacrifice and self-deprivation. Yet, is this a misconception? Midway, the author does a volte face and begins to make us wonder if we were wrong all along. Are mothers really as passive, as voiceless and as meek as they seem to be? Do they have a plan, after all? Could they have have a hidden spine reinforcing their spine? Could they, in actual fact, be master manipulators of all the people around them?

In the novel, Mai (mother) is the ever-burdened mother to two children born into a well-to-do zamindar family in which three generations live together along with household help—Mai and her husband, his parents and Mai’s two children, Sunaina and Subodh. We experience the narrative through Sunaina (and Subodh) and watch Mai who is a “silent spectre moving around, taking care of everyone’s needs.”

“Mai was always bent over. We should know. We’ve been watching her from the beginning. Our beginning is her beginning after all. She was bent over right from the start, a silent specter moving around, taking care of everyone’s needs.”

We reel from the patriarchy of the times and watch how Sunaina processes the workings of a patriarchal system that has been internalized by the grandmother and her daughter-in-law. We smart from the treatment meted out to Sunaina by the system and also notice how that same system lets her younger brother grow into a human being who knows exactly what he wants.

As the story moves from the early years of Sunaina’s childhood into teenage and then into the children’s adulthood, we begin to see Mai through their reupholstered eyes. In the early years, we see their greed. We see the arrogance and entitlement of the grandparents, the husband and the children and we are unable to understand how Mai won’t speak up and rail against it all. She would rather serve and be the good daughter-in-law. Sunaina thus begins the profile of their mother—her real name will be told to us much later, thus conveying so much even by this namelessness— by saying, “We always knew mother had a weak spine. The doctor told us that later.”

Soon, we begin to learn things that may not be mentioned except in hushed tones. The children’s father has another woman in town; everyone knows about it but would rather pretend to know nothing. It’s clear that the grandfather is not as much of a saint as he was initially portrayed to be. Some strange things happen and we experience them all through the eyes and ears of a young Sunaina.

What is clear is that Mai leads a life of extreme emotional abuse and deprivation, thanks to both her parents-in-law and her husband; yet she continues to bow down, stay in purdah (behind a veil) and she prefers to not raise her voice or speak up. The children speak up for her until they one day they realize she could do so all along, after all. At crucial moments in a family rift, Mai even tended to cross battle lines.

Mai had let us down often. She had weakened in the middle of the battle again and again. She would be behind us while we were fighting. Suddenly we would see that she was standing with the enemy. We would lose our equilibrium: mai had changed sides.

A pained, feeble, oppressed thing who had emptied herself of all content. Who had made herself open and empty for everyone to fill with whatever they liked.

We also discover that Mai speaks up in defiance against her in-laws only when her children’s futures are threatened in some way by the fetters of the rigid past. Mai, it turns out, does have opinions. She isn’t exactly a vassal or a vessel. She chooses to fight just so that her daughter won’t be oppressed.

As their mother’s inconsistencies surface, the adult children feel increasingly manipulated. Mai does have a choice and she is not without agency. What we perceive as Mai’s passivity is merely her choice to not scatter her words that she must not. It shows thought and premeditation and smarts where we believed none existed at all. This is a revelation for the children of the story as well as for the reader. Nothing is as it seems.

This novel was revelatory simply by reaffirming some aspects of my own life. I saw my mother in Mai and I relived the many moments when I found my own mother irrational just because she was skewed by other feelings and considerations that were hard to explain away. I recalled the number of times I was told by both my children that I manipulated them all along and that as adults they were now on to me.

The situations in Mai Silently Mother reminded me of my mother-in-law’s own challenges. When I found my mother-in-law helping out daily with handing out my father-in-law’s medications to him both morning and night, my husband and I raised an objection. She was already spread thin, we told her: “Why are you taking on yet another task when he is cogent enough to manage the task on his own?”

My mother-in-law didn’t think it necessary to stop doing it—both out of love and out of a sense of duty. I was frustrated. It was one more thing that had been piled on to her plate. Why didn’t she protest? I reminded her that almost six decades ago she had spoken her mind so forcefully to improve her children’s educational prospects. “That was a big move for you,” I said to her. “Why can’t tell you tell dad that you’re too tired to do one more thing?” To that her response was straightforward and ended any and all argument: “My children’s education was very important to me. So I fought for that. The rest do not matter enough.”

In the 1970s one of my sisters-in-law mounted a cruel campaign to bring my mom up to feminist standards--lobbing The Feminine Mystique at her and criticizing the family-oriented path she was on. Whether she “chose” that path can well be debated. But my mom was a genius at loving and providing, and my family would have been bereft without her beautiful contributions. So when I read this line--“All these skills add up to a human of enormous potential”--I thought: maybe the contribution of a great mother to her family IS potential realized, and more important than the one the profit-focused CEO makes? Motherhood shouldn’t be viewed as a wasted life or a missed opportunity. Maybe, for some women, it’s the highest calling.

Good