UP AGAINST A WALL

This European favorite from the sixties is itself a metaphor for the unending monotony of immurement. It didn't end quickly enough for me.

Five summers ago I lived for a month in Marnay-sur-Seine, a village two hours from Paris. At last count the village of Marnay had 218 people, not including those interred in the cemetery at the end of the only road in the village. I stayed in an ancient building in Marnay—cut off from husband, children, friends, cafes, shops—where the only sound of life was often the noise of a pebble dropped in the river.

I dare say that if cobwebs made noise, the spiders of Marnay would have been very loud indeed. By the time I went about my morning cup of tea, the sparrows were outside my ivy-laced walls, tweeting and dashing between the bell tower and the other rooftops to announce the dawn of a new day. When the bell sounded the hourly warning, the birds scattered away from the belfry in a frenzy. I fell into a pattern, too, like them, driven by the clock.

The sounds changed in the weekends. Sometimes I heard a hard splash. A holler. Someone had jumped off from the highest point of the bridge into the waters. Then there were lazy, sudden picnics on a wooden table below which a boat licked the waters. On the table, baguettes, honey, jam, knife, and a newspaper opened to a scandal that rocked Paris but hardly made a splash in a village like Marnay-sur-Seine.

It's not that sort of solitude—which is a rather pleasant reprieve from the grind of our daily lives—that I happened to read about this week. The solitude I confronted in the book is maddening, alarming, discombobulating, gut-wrenching. This sort of solitude nulls out the constant human quest for alone time and private space. This solitude is a deprivation. Yet, the end of the book, I’m left with one question: Is it deprivation? Or is it salvation?

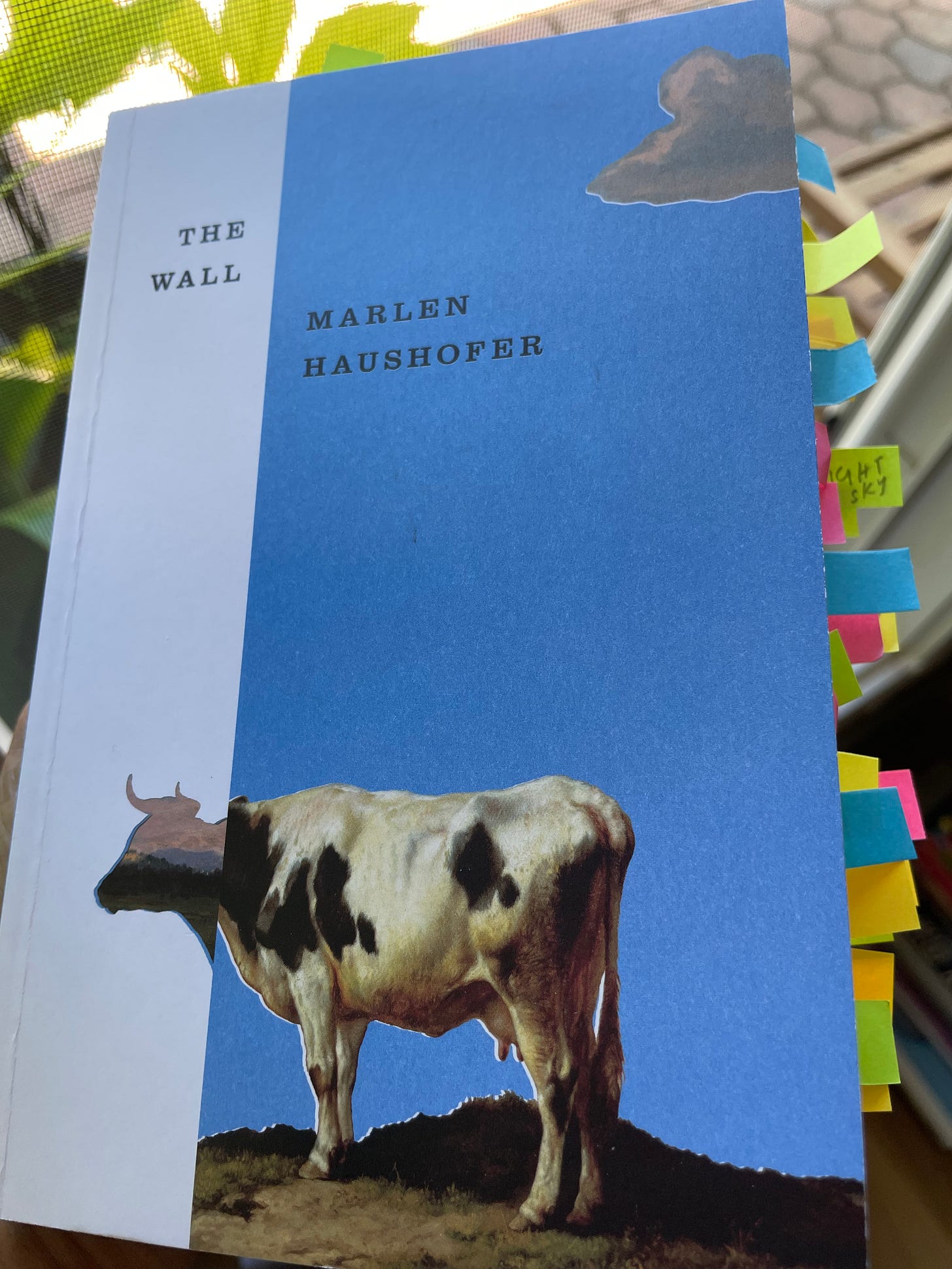

The Wall by Marlen Haushofer raises all sorts of questions. In the interests of full disclosure, I will admit that after a hundred pages, I skipped a hundred pages because I simply could not bear to read much more of it.

Yet this is a lyrical work with many moments of introspection and spirituality about what it is the protagonist feels about her life thus far. that The translation from the German by Shaun Whiteside is engaging despite its density. Imagine reading 230 pages of what’s mostly a mental exercise in how to make it through one more day. Except for some paragraph breaks, The Wall is a relentless exercise in one woman’s resourcefulness and staying power when she’s left by herself. The success of The Wall is in its ending. It’s obvious that something has changed on the outside of the wall. It’s also obvious that something has changed on the inside of the protagonist.

While vacationing in a hunting lodge in the Austrian mountains, a middle-aged woman whose name we are not told finds herself in a strange predicament. She awakens one morning to a nightmarish scenario. An invisible wall separates her from the rest of the world as far as the eye can see. Through the wall she notes a man bent over a plant unmoving, a bird or two against the ground lifeless. She alone is alive and so too is Lynx, her cousin’s dog. Soon she discovers a cat and a cow wandering alone in her space. The existence of such a book—on the very essence of existence—has been mindblowing

.