TOMATOES FOR ME

The publication of a sweet children's book about tomatoes coincided with the waning of the tomato season here in the San Francisco Bay Area and made me think of my late mother.

The tomato season is ending here in California, yet I see plenty of tomatoes at our local farmers’ markets now. At every stall and in stores, the bins overflow with the most luscious tomatoes: Early Girl, Brandywine, Celebrity, Beefmaster, Big Beef, and Supersteak. Some of the heirlooms I see in bins that are out for a quick sell are so misshapen and large that they need to be called melons. I buy them anyway. They’re dripping with juice.

I suppose I can never have enough tomatoes at home. I prefer to never run out of this fruit. A few days ago, my friend Vasanthi bought ten pounds for ten dollars at the farmers’ market. Today she made chutney with nine pounds of them. She says she likes to do this a little after the peak of tomato season when they’re juicy, cheap and available in plenty. In her blog post, Vasanthi says she eats her tomato chutney with a host of other snacks, wraps, breads, idlis, dosas or even a ladle of freshly cooked rice topped with a teaspoon of sesame oil or ghee.

The chutney or dip is a given in every Indian home. The olive bread I buy at the farmer’s market from Adorable French Bakery is so delicious with my coriander-mint chutney. I love eating curd rice with a spicy chutney made of ridge gourd, a vegetable popular in India that now grows abundantly in California’s central valley. Chutney is manna. It presents options. I can whip up a quick meal with a slice of bread or a warm roti or paratha whenever I have some vegetable chutney.

The earliest memory of a chutney is the tomato chutney that my mother made for a quick snack when I was growing up. On a frying pan she roasted two slices of bread with ghee. She pressed several dollops of the tomato chutney on one slice and then topped it with the other toasted slice. It needed to be eaten hot off the griddle, yet it was too hot to eat. But I was dying to bite into this slice of paradise. Her tomato chutney was quick and simple, yet I’m unable to recall exactly how she made it. Did she use finely diced onions at all? I won’t exactly know until I experiment with several recipes myself. I know that taste and smell are stored somewhere in the recesses of our brain and they often return to us perfectly intact when we aren’t expecting it. They bring tears, too. I will discover the recipe as I go, I know.

This morning, a relative who seems to have an uncanny feel for recipes and food hacks told me she doubted my mother would have used onions. She felt that people of that generation especially in South India did not gravitate towards onions. She had a point. My mother’s father would not even admit any produce other than those grown locally into his kitchen in North Paravoor in Kerala. He never consumed “English” vegetables, those introduced into India by the white man. In my maternal grandparents’ home, I never set eyes on tomatoes, peas, cabbage, carrot, and onion.

My mother’s cooking style must have been informed by life in her parents’ home. There were other influences, too. After their marriage in 1944, my parents moved to the city of Madras (now Chennai). Life in the city must have influenced and informed her cooking and eating habits. I wondered what spices my mother may have sought to use as she set about making tomato chutney. Could she have used sambar powder or did she simply throw in a green chili or two, with ginger for an additional zing?

It’s more than sixteen years since my mother passed away. I’m disappointed that I did not care to record innumerable fine, critical details from the limited repertoire of a woman who cared more about the quality of produce and about the art of cooking. The passage below—from my book, DADDYKINS: A MEMOIR OF MY FATHER AND I—describes my mother’s intransigence with respect to cooking. She was not into adjustments. She didn’t accommodate. She didn’t substitute. She didn’t make do.

Daddykins was considerate to my mother in a Brahmin culture that upheld male chauvinism as a virtue. But every other day, he let it be known—in his wife’s earshot—that she couldn’t bear to see him sitting idly in our verandah. Whenever he sat down to read The Hindu after his morning coffee, his wife had to thrust another errand on him that had to be done right that second. She was demanding even after all her demands were met. For instance, every time Daddykins trudged back home from the vegetable market, my mother would empty the bags and wonder about the one item that he had not bought. “You didn’t buy drumstick?” she would say with a petulant curl of her lip. “Now how do I make avial without drumstick? Just go back and get it!” Daddykins protested. “Why can’t you make do with whatever I’ve bought?” he asked. She retorted that his meal and his coffee would suffer greatly if Daddykins cramped her style. Cursing, Daddykins would rumble down the road again in his scooter to buy her drumsticks after informing her that she was peevish.

One time, my mother remained inconsolable. She had been ailing from a dreadful fluid collection resulting from mosquito bites that she feared might render her leg forever gigantic as an elephant’s foot. Daddykins and my mother were en route to Doctor’s to get her condition diagnosed when Daddykins pressed the brake of his Lambretta much too hard upon seeing a cow in his path. My mother tumbled onto the road. My father vroomed off, oblivious. ~~~ DADDYKINS: A MEMOIR OF MY FATHER AND I

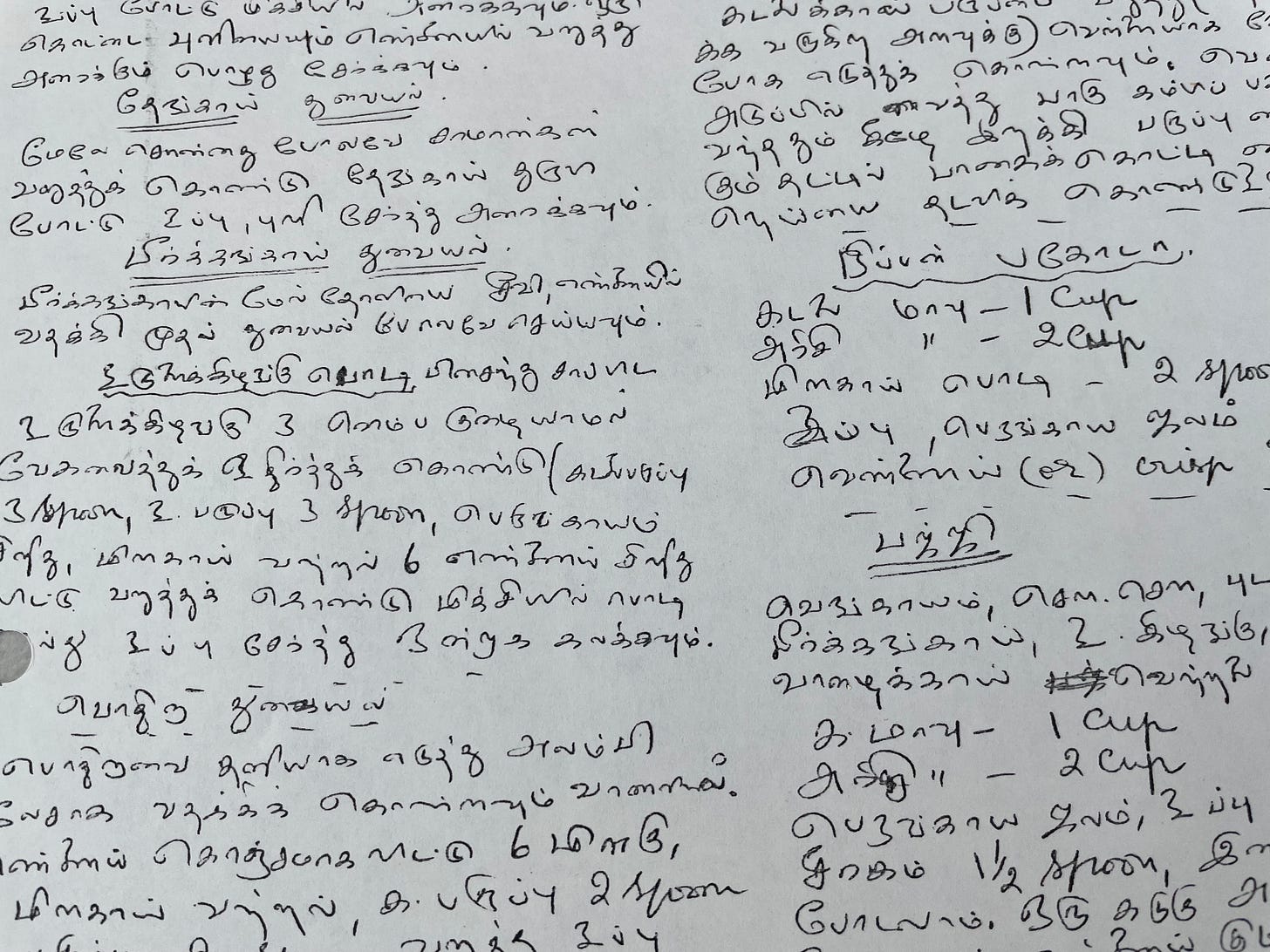

A few weeks before cancer burrowed into my mother’s brain, my sister and I decided that we must try to write down some of her signature recipes. One of them was milagai podi, a popular accompaniment to idli and dosa, that my mother had fine-tuned over the years; another was sambar powder that she got ground at the flour and spice mill near our home after she dry roasted the spices at home and carried them to the mill. The blend of ingredients bore her insignia. Since our mother’s passing, we’ve used her recipe to make ourselves a batch of spice that continues to infuse our foods with a pinch of her “kai maNam”, or a flavor of her hand, as we call it in Tamil. Thus, writing down the recipe wasn’t just the act of learning how to make something. We were recording the foods of our adolescence while inheriting an heirloom “recipe” that we would then pass on to our children.

In a recent children’s book, Tomatoes for Neela, written by the host of Hulu’s Taste the Nation Padma Lakshmi and masterfully illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal, I was struck by the way in which Padma Lakshmi told the story of a mother and child through their time together in the kitchen. Tomatoes for Neela is aimed at children but I suspect every mother reading this to her child would want to call her mother as soon as she turns the last page of the book. The illustration by Martinez-Neal is magnificent, bringing the three women in the story, myriad tomatoes, an eclectic kitchen, Peru, the Spaniards, an Italian grandmother and an Indian fruit vendor into relief in a warm, accessible way. The intriguing history of the tomato is conveyed, too. The Europeans were fearful of the pretty berry for the longest time and for years tomatoes served as table decoration in countries like Italy. Throughout the book, the story of the origin of the tomato doesn’t ever take away from Neela’s own story.

Neela is precocious and fond of her grandmother (“Paati”) far away in India. She loves “listening to her amma tell stories while they cooked together.” Neela copies the recipe from her as her mother jots down stuff into a book open in front of her. This is a kitchen that embraces every dish in the world. The trip to the produce market is revelatory, too, about the various types of tomatoes that are sold in the market, hinting at the diversity that’s possible everywhere. The trip offers another teachable moment about the heirloom tomato—a specimen gnarled and marked with ridges—a reminder of both Paati and her “heirloom” cookbook back in their kitchen.

Just as the characters are shown to be Southeast Asian, the foods, too, represent many regions of the world. Hummus must coexist alongside dosa, sushi, and ceviche. In one of the most moving passages in the book, Neela realizes that tales about food and people are often passed down from mothers to their daughters during the act of cooking.

Tomatoes for Neela now graces my kitchen. The book made me think about my mother-in-law back in Vellore in Tamil Nadu who has taught me so much. She is 83, a storyteller par excellence who digresses, just like her son. However, unlike Scheherazade (and just like her son), she always returns to the main point. I’ve learned to make many dishes celebrated in the Tanjore district from her while standing next to her in her kitchen. Over the years, she has written up many recipes for me. I do need to call her for more.

Lovely article! South Indian foods passed down through generations are healthy too. Don’t use much oil. Proteins from variety of lentils and the do’s and don’t advise from our grandma’s is still fresh in my memory.

Wow!