TO LIVE AND LET GO

When space is at a premium, the living matter more than the dead. Singapore’s pragmatic attitude is a wakeup call to those who will go.

I was tickled to death recently while reading Mr. Bad News, a memorable piece of nonfiction from master craftsman Gay Talese. In his 1966 profile of Alden Whitman—who was an obituary writer at the New York Times—Talese drills down into the life of a typical writer in the obituary department. At the New York Times, obituaries are written (and constantly updated) well before the famous subject of the obituary chooses to die. Talese says that one of the hazards of the job is an “occupational astigmatism” that can be quite embarrassing.

“After they have written or read an advance obituary about someone, they come to think of that person as being dead in advance. Alden Whitman has discovered, since moving from his copyreader’s job to his present one, that in his brain have become embalmed several people who are alive, or were at last look, but whom he is constantly referring to in the past tense.”

The life of an obituary writer may seem like a dead-end journalism job. Consider this, though. There is always a fresh crop of material. There may often be surprises, too. Someone who is too young to leave the world can decamp in the most unexpected way and, as Talese is ready to point out, no one is getting out of this place alive anyway.

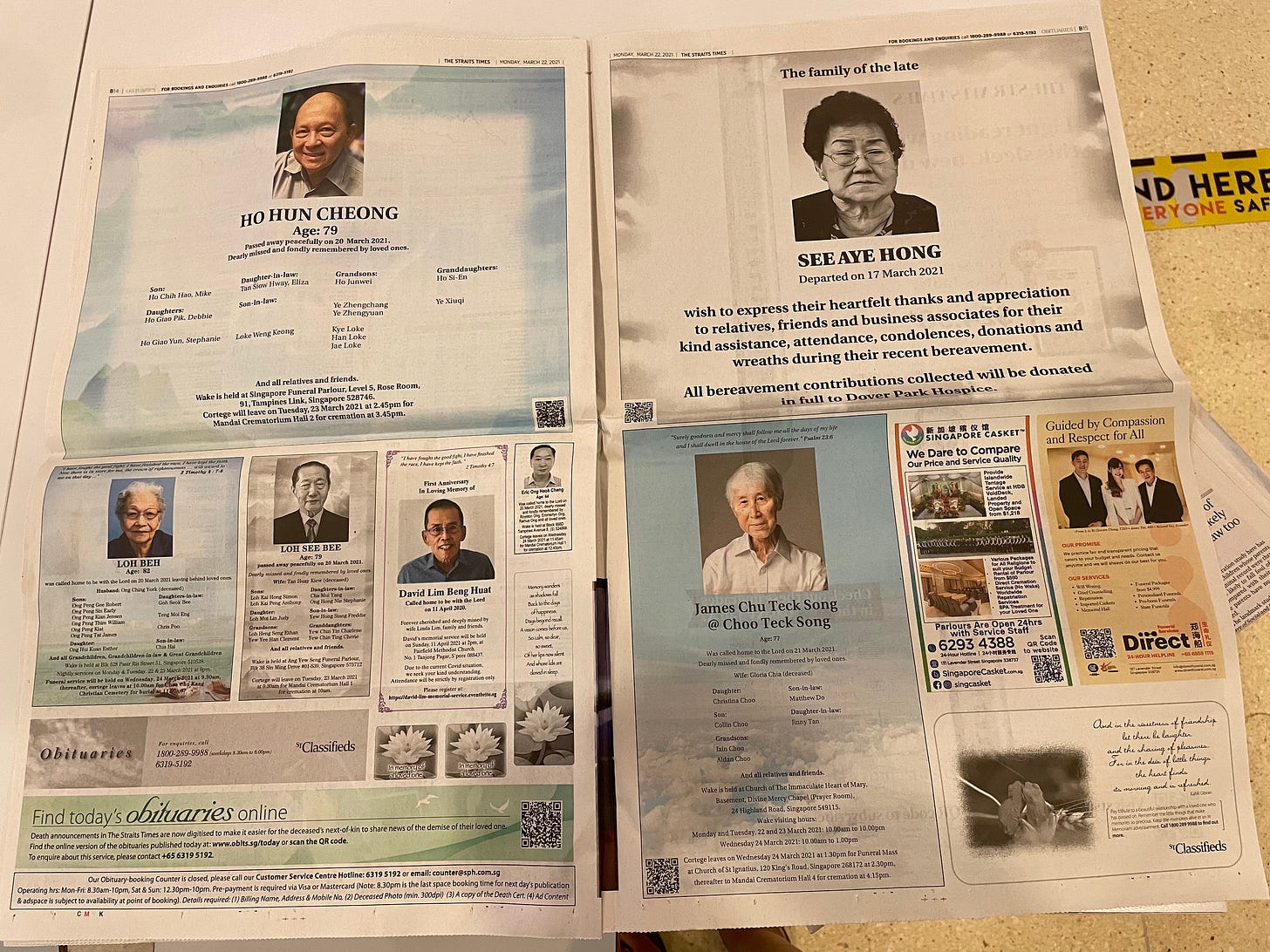

It was while reading The Straits Times—the day after I read Mr. Bad News—that I discovered that the paper had set aside several pages of real estate to obituaries. Not only was the newspaper (like every other news publication in the world) making money on death; other businesses such as casket makers advertised their wares right below the pictures of souls who had passed on. A few of the death notices in The Straits Times startled me. They spread out over at least half a page. A staggering amount of real estate in square centimeters. If land were at a premium in a paper, what about in the city itself? With some 5.6 million people in an area three-fifths the size of New York City—and with the population estimated to grow to 6.9 million by 2030—Singapore’s price per square foot has been soaring. It seems to pay close attention to managing its land as efficiently as possible.

In such a country, the apportioning of land for the afterlife seemed like an unreasonable expectation. The division of its limited amount of resources in terms of physical property—while keeping in mind the sentiments of its many different communities—had to be a monumental challenge. This was not just a problem for this nation. World over, we were having to find ways to dispose of the dead in order to release space for the unborn. Still, in an island that is both a city and a country, the challenges of managing water, electricity, housing and waste are never-ending and hence I was intrigued by the way in which Singapore had gone about weighing and attempting to resolve the issue of maximizing space for the living over many decades.

To accomplish this, even as it made its master plan to develop public housing, it set about to acquire land. In 1972, the government decided to close all the cemeteries near and around the city area to conserve land. Today the only cemetery in Singapore still accepting burials is the Choa Chu Kang Cemetery Complex. Since this site has very limited space, cremation is considered to be the only viable long-term option.

In 1998, the government also announced a new measure whereby the graves at Choa Chu Kang Cemetery Complex, would be recycled after fifteen years; the families of the deceased would be informed as the date approached and the remains would be cremated and stored in government columbaria; if the deceased belonged to a community that did not cremate their dead, the remains—after fifteen years these would be minimal—would be transferred to another grave shared by many. The plan received the approval of the representatives of Muslim, Parsi and Bahai communities.

Despite its diminutive size, this country has been a microcosm of the world for two centuries. I saw how it was always on a quest to find solutions for all its people. The management of death has been a sensitive issue. Death is not perceived as an end of life in many traditions; the state of death is more like checking into a day room at Changi airport; it’s believed to be a resting place before an onward transit to another destination. To be ensured of a good afterlife, the appropriate death rituals and the manner of disposal assume added significance. Just as the Hindus believed in “vaastu” principles to integrate architecture with nature and directional alignments, the Chinese believed that some spaces were imbued with divine energy. During the colonial period in Singapore, how space was viewed in societies became a topic of debate.

“By the late nineteenth century, this debate was focused on one particular element of the city’s “sacred” geography—the burying places of the Chinese communities,” writes Brenda Yeoh, in her paper in the journal of Southeast Asian studies. The Chinese sought burial spots such as knolls and hillsides with a view but those very hills were considered prime property for development by the colonial government. Furthermore, the attitude towards the dead had undergone a change in western culture by mid-18th century. Cities in western Europe were now beginning to distance the living from the dead. It was one way in which to prevent diseases such as cholera and plague; inner city graveyards were closed and cemeteries were moved to the outer reaches of a city.

A report from the year 1952 worked on by a committee—comprised of an Englishman, a Zoroastrian, a Hindu, a Muslim, a Buddhist, a Jew, and several Chinese gentlemen from different traditions (Taoists, Confucians, Buddhists)—gave critical feedback on the burial processes and the burial grounds in Singapore. The report spit out a long list of private and public burial grounds littered all over town—some 200 or more of them—that were places that I now know as unique locales of Singapore city.

“The Honorable Mr. N. A. Mallal, in a speech in the Legislative Council in August 1948, drew attention to the fact that cemeteries which had originally been some distance from the town had become part of it, and pointedly remarked that there was now more room for the dead than the living.” ~ Excerpt from REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE REGARDING BURIAL AND BURIAL GROUNDS, 1952

There were several parts of Orchard Road where the dead were buried; another location was on Alexandra Road—600 yards from Telok Blangah Road—that had been a burial area for Hokkien Chinese; there was also a Hindu area near Lorong 3. At least one of the burial locations, Tiong Bahru, became the city’s first public housing complex, a historic district that takes its name from its macabre origins. “Tiong Bahru” combines two words—“Tiong” means “To Die” in the Hokkien dialect and the Malay word “Bahru” means “New”—to allude to what was a new cemetery. Today, Tiong Bahru is an enclave of about fifty Art Deco residential blocks flanked by charming shops and restaurants.

If the consolidation of these sites for the creation of the 1952 report was a mind-bending task, the exhuming of the graves at each of these sites and their disposal or transfer must have been far more arduous. In a previous post I’d talked about the meticulous manner in which Singapore conducts its public affairs. I came upon another while working on this story. Though the subject is morbid, I urge you to read how graves are exhumed just to understand the sensitivity with which the country carries them out. During such an overhaul of graves, ancestral worships and specific rites are uprooted, too. Families that congregated around the grave of an ancestor on special occasions, have had to find other ways to commune.

I decided to write about the city’s struggle with finding space for its dead because it’s something most of us do not stop to ponder when we look around at the rapid development of a densely populated country. The pragmatism in allocating a minimal amount of space to the dead seems to be percolating down to its people. I learned that more Singaporeans are pre-booking niches at private crematoria, even though pre-booking a final resting place is considered to be inauspicious in eastern cultures. Apparently, the reasons for planning ahead are twofold. People want to be close to their loved ones even in the niches; they also want to book them before the prices rise, a practical concern.

It takes courage to confront one’s mortality. Most human beings continue to think of death in vicarious terms, as if it happens only to someone else. I believe most of us react to someone’s death with a sort of “necrotic” empathy because a little bit of us dies inside us when someone we know passes on; we feel for the victim, for those around him or her; we feel for ourselves, too.

Every passing is an affirmation that our own wagon is hurtling to the end. This is the reason I read obituaries, to weed out any remaining doubt in my mind about the certainty of my own expiry date. The older I get, the greater the number of obituaries I will have read—just as my father had in his twilight years, keeping a count of all those who had crossed over to the other side.

Really enjoyed reading this piece! On the topic of graves and history, I thought you may find these interesting sites to explore: https://thelongnwindingroad.wordpress.com/2013/12/01/a-vestige-of-16th-century-singapura/. I have been to this kramat and the Radin mas kramat in 2017. The shacks make it impossible to find the entrance to the graveyard, but the history is very intriguing. You may find Bukit Brown cemetery interesting as well- several members of the public have been campaigning to save the cemetery from redevelopment. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-03-06/la-fg-singapore-bukit-brown

Seriously this is a topic that people need to think about no matter how uncomfortable they may feel cos disposing the dead in a manner in which we don’t end up occupying space is something that needs to be faced. Place for people to live is more important. Very nicely written cos in my opinion it isn’t an easy topic to write about.