TO CHANGE THE WORLD

This moving translation of an autobiography opened my eyes to the life of a group of people in India relegated to the subhuman.

“We were not allowed, of course, to touch the water pots. But if a rat were to fall in and drown, then it was my duty to fish out its bloated corpse. No one else would do it.” ~~~Eknath Awad.

I began reading my pick for the week on the flight from the San Francisco Bay Area to India. Beyond the excuse of jet lag and general exhaustion owing to travel, the real reason for not posting this four days earlier is something else altogether. This book was very hard to read in one sitting. The content was hard to digest.

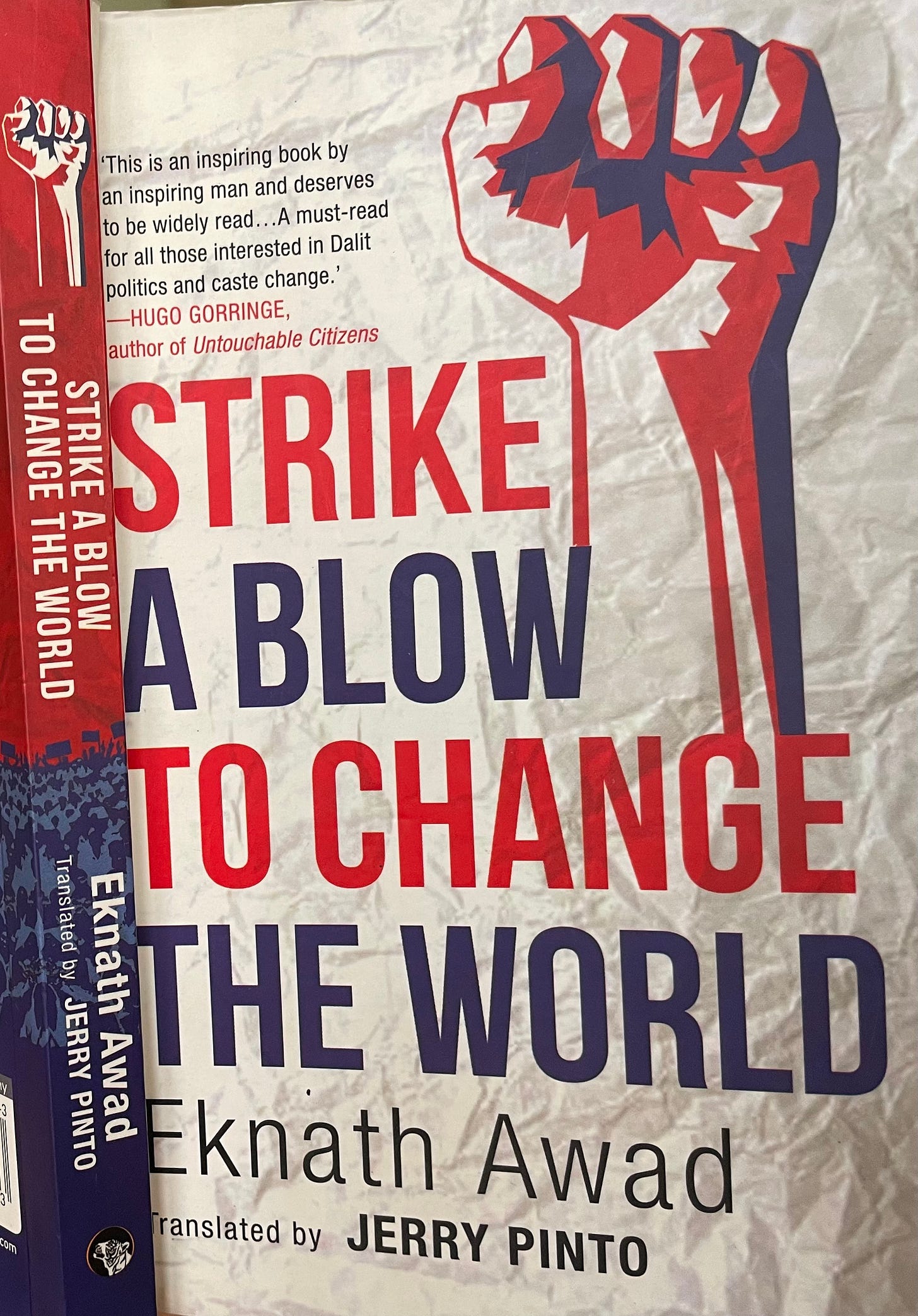

Strike A Blow To Change The World by Eknath Awad—translated from the Marathi by Jerry Pinto—is unsettling. Every chapter of this autobiography published in 2018 by Speaking Tiger invoked the discomfort I had felt for years but preferred to not address, even in solitude. Every page reminded me of my cushioned upbringing, one in which my own struggles always loomed so large that there was no room to even consider those of others whose voices had gone unheard for centuries.

This book is the story of one man—born into untouchability—who sought to be heard. Awad’s autobiography lays bare the systemic deprivation, discrimination, exclusion, and violence that has defined the lives of those castes that have traditionally been oppressed. Until his death in 2015, Eknath Awad was at the helm of the Dalit struggle in the Indian state of Maharashtra, fighting for the rights of the underprivileged communities irrespective of their caste or religion.

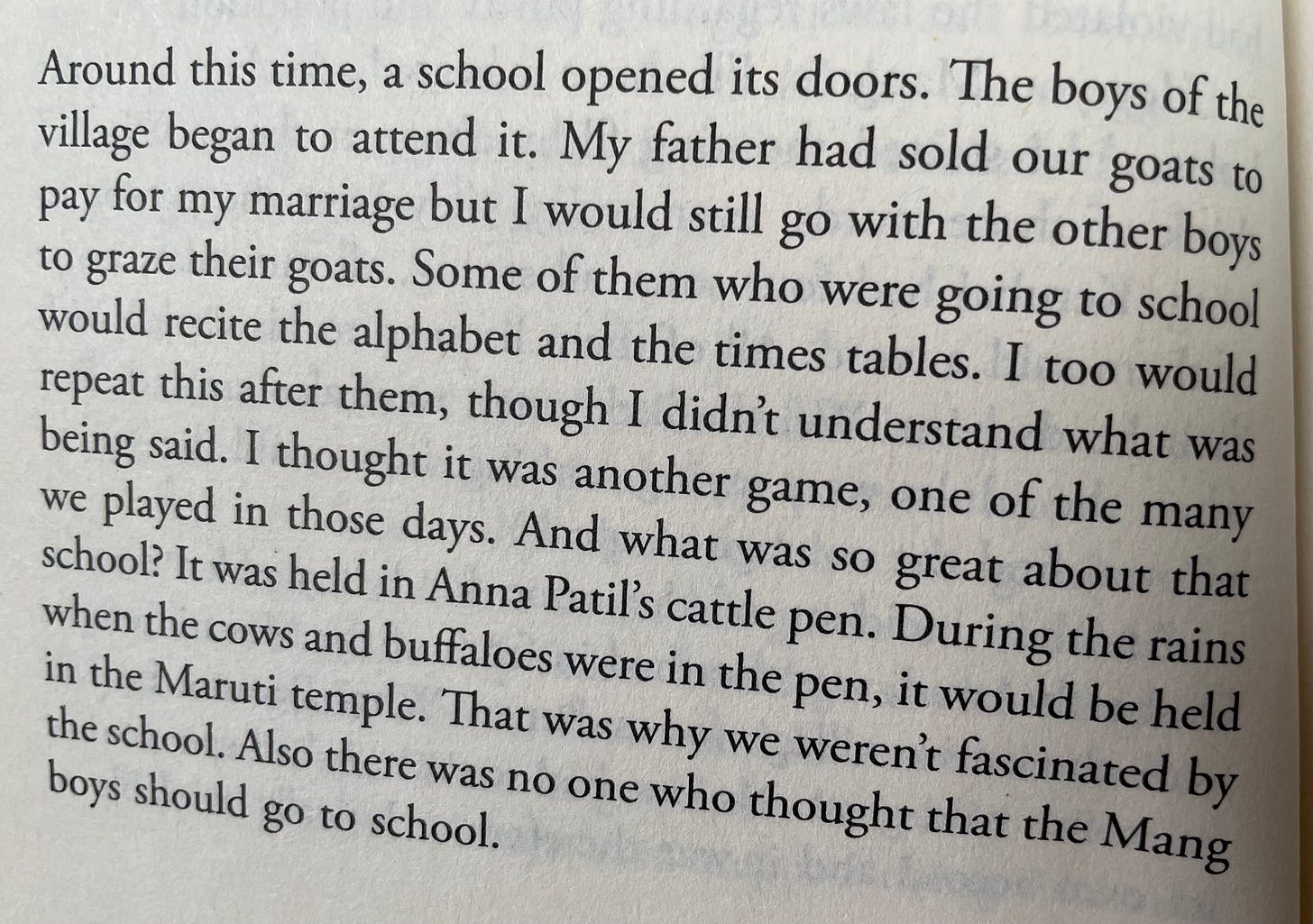

Even though he was born a mahar (one of the lowest castes in the Hindu social system) and his father was a potraj—whose life was defined by begging for daily alms—Awad decided early on that he would choose a different path. Once he happened upon education, Awad found ways to learn—and to teach himself—even when the systemic hurdles put up by the upper crust of society barred his daily access to the classroom.

On some days when there was no money to buy food, Awad plied the trade into which he had been born.

“I can still do all that I learned as a child. I can make rush bundles, I can weave rope, I can make a charpoy, I can still all do this easily. I was an expert in soaking sisal and spinning ropes from it.”

Awad was fortunate enough to receive his first exposure to school in his village in post-independence India and to have his mother’s support to pursue his academic dreams. For children from his community, however, absenteeism was a given; when food was hard to come by, his family expected Awad to work to make ends meet.

Quoting Babasaheb Ambedkar, a fellow mahar who went on to champion the annihilation of caste in India, Awad observes that “tiger milk” now coursed through his veins. He had tasted blood. He knew that education would empower him.

“The tiger inside me was asking: “Can I devour all the suffering the caste system has wrought?”

The book takes us on a journey from Awad’s earliest years when learning itself was erratic through his years of self-development as he sought to get his post-graduate degree. Eknath Awad impressed his teachers. While scholarships fueled his studies in college, his intellect made him both compelling—and intimidating—for his teachers.

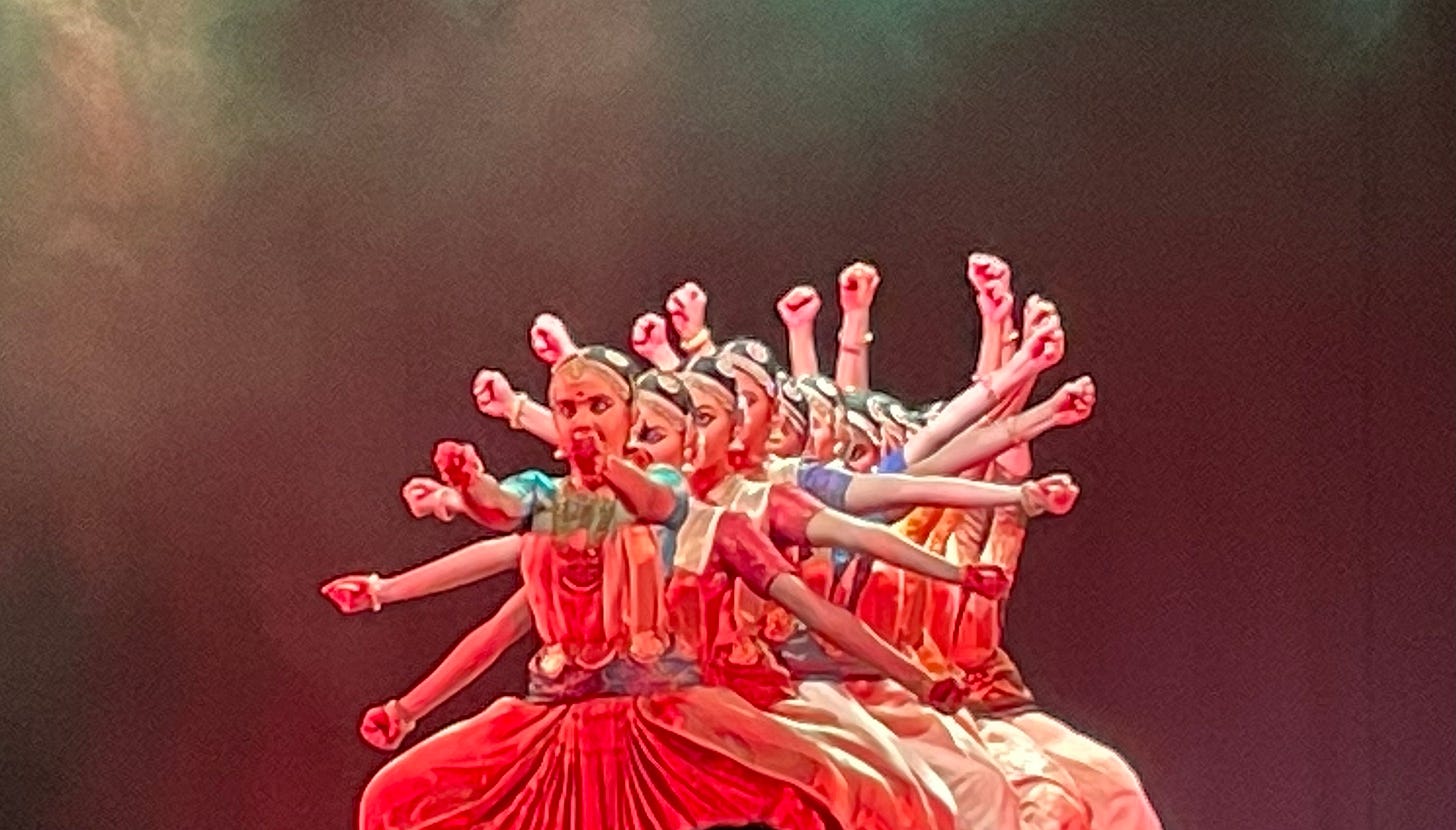

Debate was his forte and over time, his fearlessness made him a natural leader. In the 1970s, Awad joined the Dalit Panthers to foment political unrest at a time when India was already in turmoil.

“For the Dalits, this was the first or second generation that had reached college. The Emergency, Jayaprakash Narayan’s call for Total Revolution, Vinoba Bhave’s Bhoodan (The Gift of Land) Movement, the rise of the Naxalites…all this was in the air. I too was active in the Panthers Movement. No sensitive and thinking youth could possibly be neutral in this charged environment.”

Strike A Blow To Change The World made me realize how privilege begets privilege and how we dismiss entire communities for being lazy or disinclined towards education when the truth is altogether different. For those who enter and succeed in the hallowed halls of education, economic security and family support is often a given.

Education benefits everyone, of that there is little doubt. For some, however, it’s the only way out of their misery. How they use it depends on their own internal drive. While the rich often used school and college to build their social life and grow their network, Awad, in contrast, used it tactically—to hone his voice and to build political clout. Unlike others from his community, however, Awad was restive; he didn’t seek education with the end goal of finding employment. He had bigger dreams for his people. In activism he found his calling.

“It is not possible to solve the problem of untouchability by providing the Dalit with food and building a few cement houses for them. It is much more important to awaken their sense of self-respect.”

I found this book very hard to pick up to resume reading. Activism is hard work, I realized, but reading about activism is depressing because the path to creating awareness and self-respect means undoing years of conditioning and oppression. The lack of self-worth is a scar that runs so deep.

One of the most telling passages in the book narrates an incident on a bus. A conductor on the bus uses a slur to attack some passengers. He asks them why they’re behaving like people from the mahar community. Awad and his friend beat up the man for his insensitivity towards his community until, to their consternation, they discover that the conductor himself is a mahar.

“Deprivation has no joys at all. If you must swallow insults and disrespect all your life, it does not make for a life of happiness. But when a human being begins to fight the circumstances of life, when she takes up arms against injustice, then life offers another kind of exhilaration.”

When I reached the last page, I put the book away and considered it for a while. This was a memoir of a man who took his life’s mission seriously and sacrificed the safety and peace of his own family for a larger goal. As he went about trying to build the self-worth and self-respect of his people, he encountered opposition, not just from his opponents in the “higher” castes but also from people of his own ilk. The lack of self-worth had scarred people so deeply that the work of undoing the damage was hard work. Those who are ready to fight often ended up being beaten.

At the end of my reading, I could also understand, with greater clarity, the inherent anger in those who are embroiled in this fight. More often than not, violence and extreme measures are the only way to change the order of things. People tend to find comfort and security in the old order and anyone who tries to shake things up tends to be viewed as the enemy.

Awad and his family were trying to overhaul the mindset of their own people and those of others. What could anyone expect? Eknath Awad’s entire life was a battle because he dared to ask two questions: “Why not? “What if?”

Awad and his family assailed death threats with a fearlessness that renders me incredulous. This brand of activism embodied his entire existence. Just like his guru Ambedkar, Awad also embraced Buddhist principles. In a chapter in this book, he lays out why. I found it hard to swallow his outright rejection of Hinduism and his pointed attack on The Bhagavad Gita. This is his truth, however. I don’t dare wonder why.

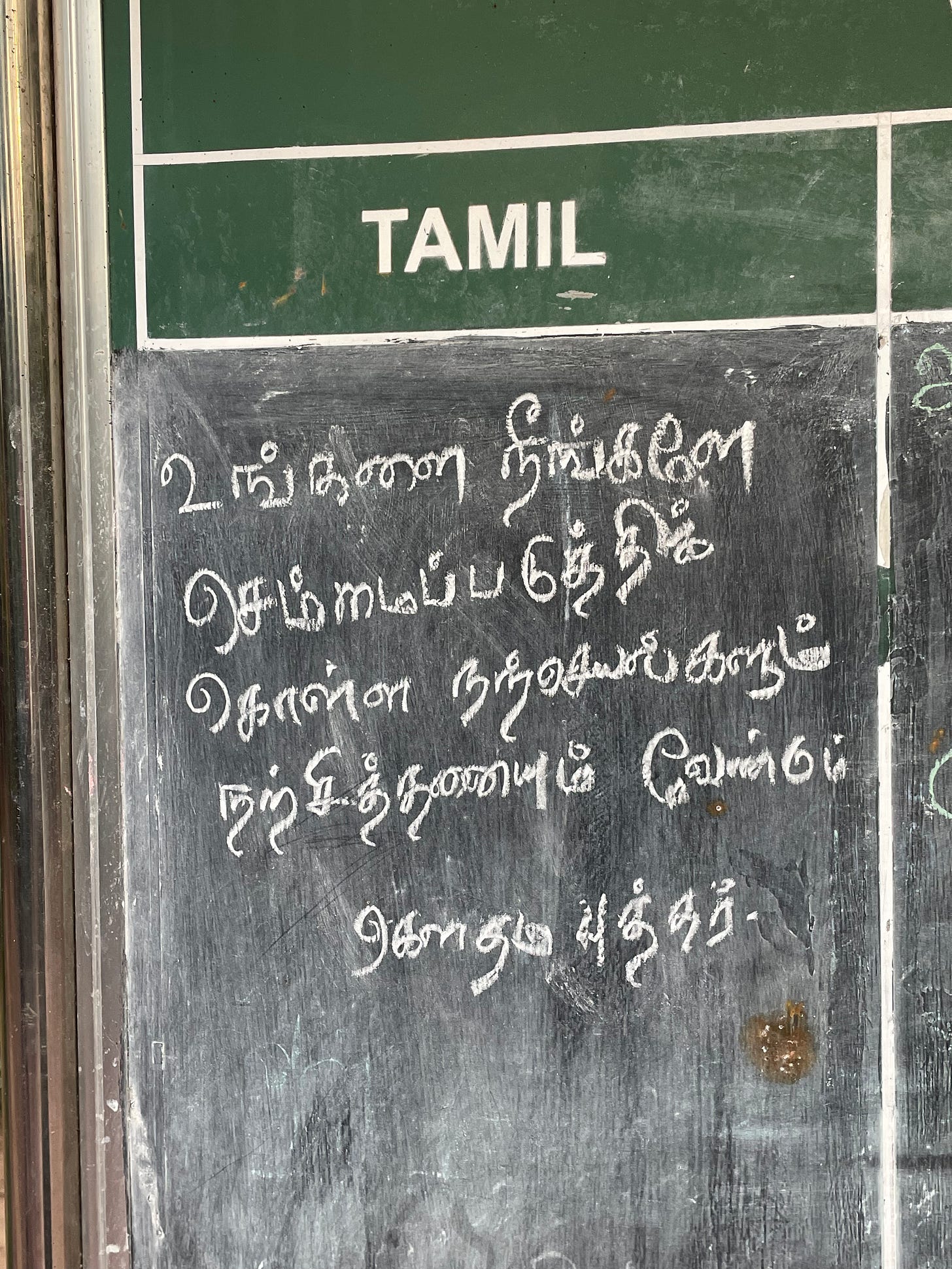

While reading Strike A Blow Against The World, I was fighting jet lag and fatigue. Sometimes, I was also resisting the intransigence of my late father’s chauffeur, Vinayagam, who was skeptical of the work of Awad when I summarized passages to him. “Amma, the cat cannot aspire to be an elephant. The elephant will never be a cat,” Vinayagam said, attempting to shut me up when I admired Awad’s persistence and vision. Vinayagam also reminded me of another truth, that it was supremely convenient for me that he was my chauffeur and general help around our house. Impertinent as he was, I grudgingly admitted that he was right while informing him that if he were absent I could also use Uber or Lyft.