THREE YEARS. FOUR MONTHS. NINE DAYS.

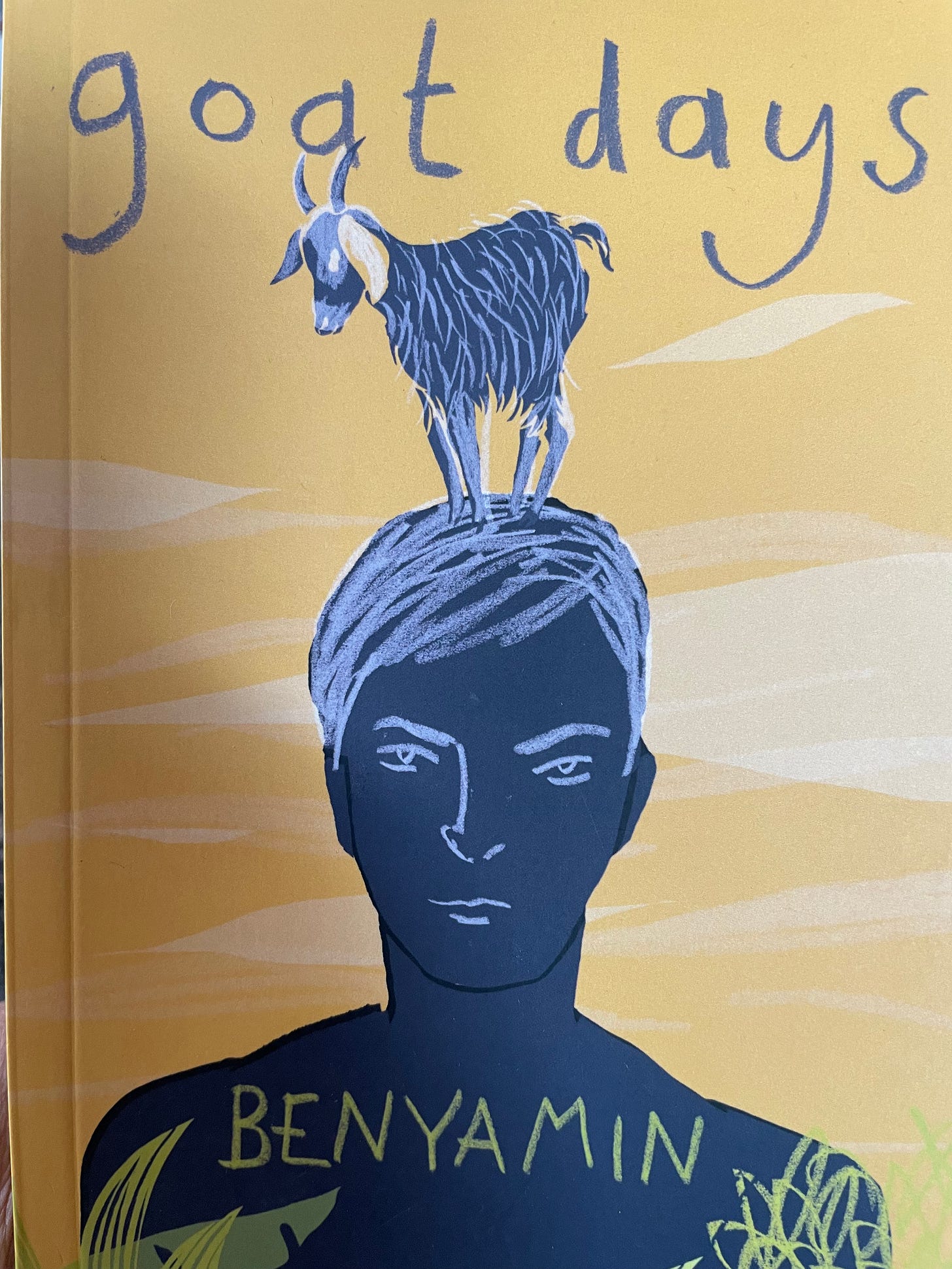

Read the book or watch the movie? Is that even a question? Read GOAT DAYS asap, please, and then watch THE GOAT LIFE when it comes soon to a theater near you.

In the wee hours of Thursday, at 1.15 AM or thereabouts when my husband on the other side of the world wondered why I was still awake, I turned to the last page of Benyamin’s Goat Days.

When I’ve just finished reading a harrowing tale, I let out a sigh of relief that thanks god that it’s only fiction. Dear fellow humans, unfortunately Goat Days is not fiction, and thereby hangs a tale. In Goat Days Benyamin has written the true story of Najeeb Muhammed, a man whose life story he heard about when he, Benyamin, was working in Bahrain, an island country in the Persian Gulf region.

The author’s real name is Benny Daniel and he is a prolific writer in the Malayalam language. I’ve known of him by his pen name for about a decade and I’m kicking myself for not seeking to read this work sooner. During the time I attended literary festivals in India (between the years 2012 and 2017), Benyamin was a popular panelist on the literary circuit. Besides many other award-winning novels, some 250 editions of Goat Days have been published in the original Malayalam and the book has been very widely read since publication in 2008.

Great books make me feel alive. While reading them, I tell myself I dare not die of a stroke or a heart attack or perish in an earthquake before I reach the end of the story. I actually need to see through the book with a rabid urge that feels almost like an out of body experience. Goat Days put me in a trance.

That’s the effect great storytellers have on our entire selves. Nothing, absolutely nothing, comes between you and the story. Goat Days makes you smile, groan and shed tears. (It could make you want to throw up.) The pages begin to reek of dung and urine, blood and sweat, and placenta and lamb—and roasting mutton. You die a little inside when a goat in the story is castrated. You die some more when one goat actually dies.

Goat Days opens with two young Indian migrant workers from Kerala named Najeeb and Hameed in Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia. The two men are trying to flag down sentries and policemen just so that they can actually get caught and be incarcerated. It’s not clear why they long to enter a prison. It takes extraordinary effort for them even to be noticed. In the eyes of some people others are sub-human. The invisibility is a fact of life. By and by we discover that Najeeb and Hameed wanted to land up in prison simply in order to survive.

In the jail, meals were served after different prayers. Around noon, after the dhuhur prayer, lunch was served. It was always some kind of Arab biryani called majbus or kabsa. It was brought in large plates, one for at least ten people. We would sit around the plates in Arab style and eat. The meat in the biryani was different every day: chicken, mutton, camel. When it was mutton, I wouldn’t eat that meal.

“What is past is past. Forget it, and try to eat something.” “There is no place to improve health like the prison. We must return at least as we landed here. Don’t make your wife lament on seeing you when you return. Only we need to suffer what we have endured.” Hameed tried to console me with such words. Despite all the kind words, I couldn’t be consoled. Even the word mutton made my eyes moist.

Why is Najeeb unable to look at a piece of mutton ever again? What has happened before he arrived in jail? Why does he feel some kinship with the source of this mutton? Thus begins our curiosity and the story of Najeeb.

We watch a young man from Kerala risk all his money to make some money in the Gulf. As he desperately awaits his papers from Riyadh, he begins to dream of a more “upgraded” life in the Middle East with some of the basic conveniences that come to us as we enjoy a little more money: “an AC car, an AC room, a soft mattress with a TV in front of it” and so on. When he finally lands in the airport at Riyadh, it’s not clear why his boss isn’t there to receive him. As he and another young man named Hakeem await their employer, the airport steadily empties. Night drops its eerie curtain. A man arrives. That man, they conclude is their “arbab” (a Persian word that means "master" and "landlord").

Hundreds of Arabs had walked past us wafting enticing fragrances. I had joked to Hakeem some time earlier that a new perfume could be made by distilling the urine of the Arabs who use perfume every day. But my arbab had a severe stench, some unfamiliar stink. Likewise, while the other Arabs wore well-ironed, pristine white clothes, my arbab’s dress was appallingly dirty and smelly.

Hakeem and Najeeb are unceremoniously ushered into the arbab’s shabby pickup in which the locks do not work. “The doors were fastened with rope. Springs peeped out from the seat cushions.” They’re told to climb into the open section in the back. It was as if they were pieces of cargo. For the next countless hours, they are thundering into the unknown until they reach a plain with not a tree or a building in sight. Hakeem is forced to alight and is led somewhere far away and the arbab returns to the truck to ferry Najeeb along to yet another far away destination by the faint light of the night. By the light of the morning hour, Najeeb realizes with horror that he has been sold to this barbarous man to manage hundreds of sheep in the desert. Three years. Four months. Nine days. That’s how long Najeeb and Hakeem slave in the desert, each under a different master, in the most inhumane conditions.

Goat Days is about the power of the human spirit and endurance. Here in America, they might call it grit, “a personality trait possessed by individuals who demonstrate passion and perseverance toward a goal despite being confronted by significant obstacles and distractions.” Another meaning, as described by Merriam Webster, is sand or gravel. Goat Days involves copious amounts of both kinds of grit.

For me this work, both book and cinema, posed the following questions: Why do some humans need to live even when nothing in their lives seems promising? Why do some crumble where others will not, physical limitations aside? Where is that fine line between victim and murderer? Will faith and trust in the Almighty keep you alive when all else is lost?

Goat Days reminded me of what I had observed in Singapore, a reality of life in the island nation that bothered me immensely. Young men from Tamil Nadu and other parts of the Indian subcontinent worked in menial jobs all across Singapore, making this efficient city run like clockwork. Thanks to these worker bees, Singapore is beautiful and spiffy, and those of us who visit it rave about it, forgetting that the country owes much of its efficiency also to its migrant population. Were these low-brow Indian workers in Singapore being treated well? Who knew? How many Najeebs were enslaved simply to send money back home to their families? How many would admit they felt like bonded coolies caught in an unending nightmare? These workers will remain a silent majority, just as Najeeb in the story.

Their stories must be told, however. Goat Days is a noble endeavor that has brought the writer much acclaim, for in the telling he and his translator Joseph Koyipally have shown us their capacity for empathy. This book is so upsetting that I’d find myself opting to skim through some paragraphs knowing what was contained in them. I had to force myself to do justice sometimes.

This was a very timely pick on my part and I acknowledge my sister’s role in it. She called me from Singapore to say that she had just watched a movie called Aadu Jeevitham (The Goat Life). For sixteen years, an illustrious movie director in Kerala by name Blessy Ipe Thomas had been wanting make a movie based on Goat Days. It was just released in March 2024 in some parts of the world. The reviews and comments here tell us how lofty the goals were for this international movie project. It’s releasing soon in the United States and is currently the 3rd highest grossing Malayalam film of all time as well as one of the highest grossing Indian films of 2024.

At 264 pages, Goat Days is a swift, heartbreaking read. Like Najeeb, our main character in the story, once you’ve lived out your days in the pages beside these goats, I doubt you’ll eat mutton again. It’s a story that every reader will read with a sense of urgency. Once you’ve read it, you’ll walk over to your frenemy neighbor’s to bleat endlessly about it and end up gifting them a free copy.

“Many of them leave their home lands, resort to crossing borders, face ethnic conflicts, and political and communal interventions in their efforts to seek employment abroad to improve their life. Behind every single person who ventures with grand aspirations, countless tearful eyes await their return to their homeland. Occasionally, people disappear amidst the harsh realities of exile, and their tragic tales deeply resonate with many. It's a time when justice appears distant, as individuals grovel before others just to secure a meager piece of bread. Unfortunately, even in this modern era, there are places where a few wander into the desert, losing themselves and meeting their demise due to thirst. In contrast, my homeland, Kerala, a state in India, is a place teeming with inspiring life stories where individuals have ascended from humble huts to magnificent palaces.”

~~~ Blessy Ipe Thomas, Indian film director and screenwriter, THE GOAT LIFE