THE WORLD ACCORDING TO BUDI DARMA

An Indonesian writer drags us into a college town in America's Midwest. Although sanity devolves into insanity in an instant in every tale, we realize we're buffeted by the same feelings and longings.

In 1973, the late Indonesian writer Budi Darma—a reputed writer and a literary critic in Indonesia—made an observation on western perceptions about literature from the east. He’s alluding to an attitude, in the western world, that its perception of literature is a marker, a gold standard, for the rest of the world.

“They see the Eastern world as something exotic, as interesting because of its foreignness. To them, local color is immensely fascinating. Their attitudes towards wayang, batik, Balinese dance, and the like are often shaped by their exoticist values. And the same goes for their attitudes toward the literary works they translate. Reading literature not as literature, but rather as the manifestation of Indonesian writers’ opinions about Indonesia’s problems—this is what happens when such attitudes are held.”

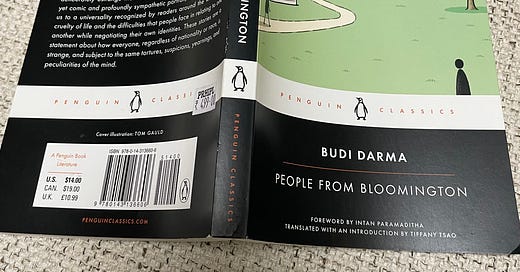

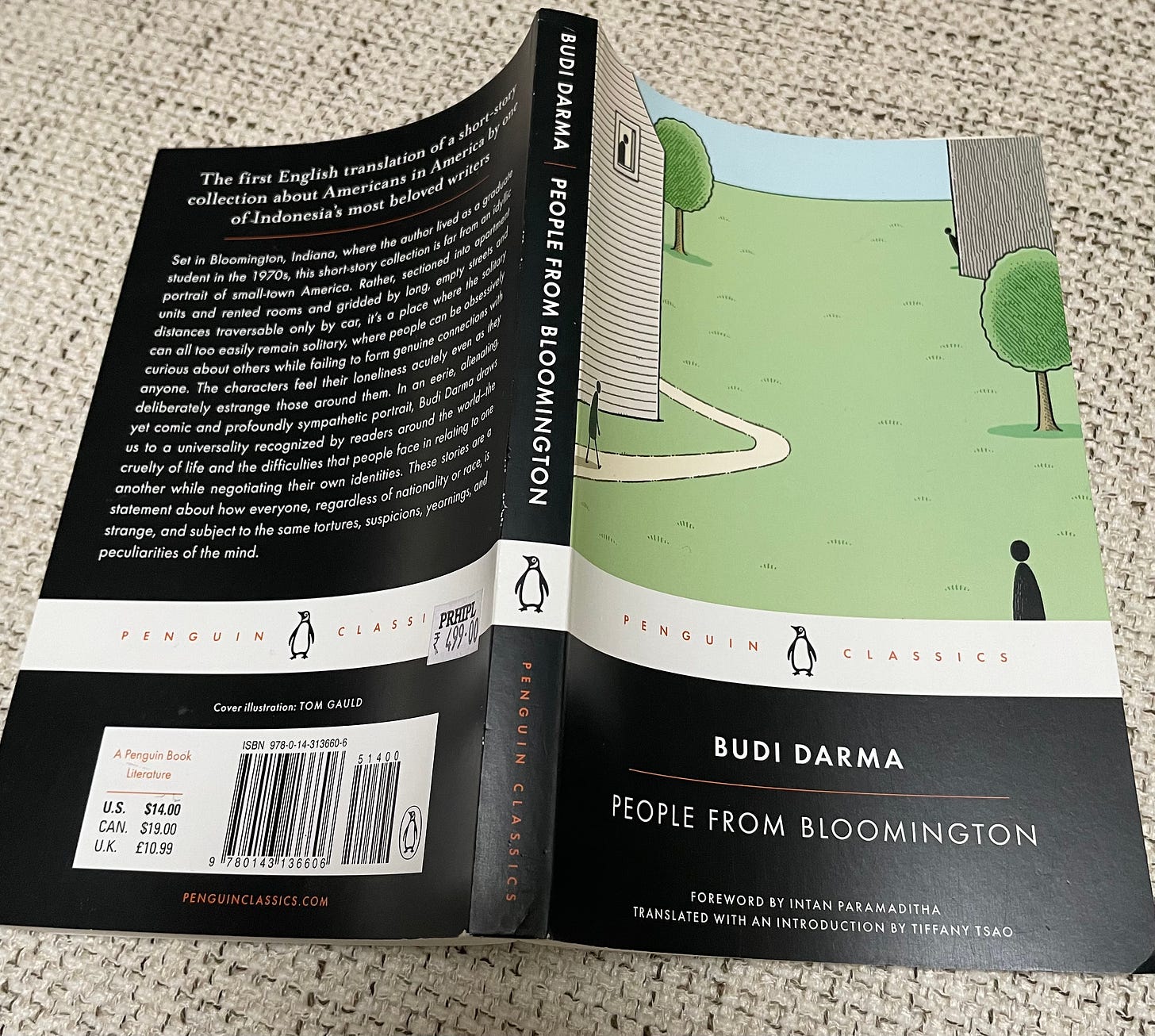

In an essay about Budi Darma’s PEOPLE FROM BLOOMINGTON, translator Tiffany Tsao comments on how, “in a global literary climate that tends to value Indonesian literary works as ethnographic material on Indonesian culture, Budi Darma’s PEOPLE FROM BLOOMINGTON quietly refuses to play by their rules”. Darma shows us how it’s possible for anyone from anywhere to write about a place. Tsao’s observation is a wonderful launching pad from which I can also underscore the value of literature from around the world. What is needed, in fact, is honing our skill to divest a work of the place in which it belongs. All we begin to see then, when we unravel the layers of culture, tribe, tongue and fetish, is that the people are all human, just like us, with the same longings, frustrations, fears and angst.

PEOPLE FROM BLOOMINGTON is a clutch of stories of people in middle America. Save for one revelation in a story titled Joshua Karabish, it’s not even clear that the narrator in all the stories is anything but another native in Bloomington. I found the whole premise mordant and instructive. Darma shows us the mirror, that we’re all the same, wherever we are in the universe. The stories in this collection are evocative of tales by T. C. Boyle and Darma’s stories, just as Boyle’s, are based on reality. Yet, as the story progresses, the characters get progressively strange and skewed and the absurdity of the situation is jarring.

Every tale manages to somehow ensnare and bewitch us with the sordid details of everyday life. We see how insanely angry a man (the narrator) becomes when he notices a scratch in the tail of his car. The narrator in The Family M goes to extraordinary lengths to be obnoxious and malevolent. All we know for a time is how much angrier the narrator gets with every day that passes. Soon, he crosses the line. His behavior is abominable, even inhuman. On the day before Thanksgiving, though, he says that many of the cars in his apartment building are gone.

“I felt terribly alone. While it was true I didn’t have any friends, and while it was true that I often felt lonely, I’d never felt as lonely as I did then. That afternoon, I watched nearly forty cars pull out of the parking lot, and as night fell, another fifteen cars disappeared.”

In one unexpected shift, we, the readers, are empathetic to the narrator’s wistfulness and despair. As the story rolls to a close, it’s impossible to not feel an ineffable sorrow for a realization that came too late. In almost every story in the collection there is a reckoning that arrives late and at a great cost to all.

Joshua Karabish is a tale about insecurity. A foreign student in Bloomington shares a room with a poet who suffers from some unnamed disease. We find out in the end that the cancer inside the “foreign student” is really a combination of insecurity, greed and jealousy, the green-eyed monster that blinds him and makes him actually justify his plagiarism. Like every story in the collection, it’s gripping until the last line.

The Old Man With No Name underscores one man’s fear of another. It’s a heartbreaking tale about the indifference that can exacerbate loneliness in the aged. In Orez, we meet a boy born to a couple who are told that in all likelihood their offsprings will likely not be born normal. They give birth to a child who has a large head and a small body and it’s clear from day one that he will spell trouble as the grows. It’s a strange piece of fiction in which Orez has almost feral and bovine characteristics; he’s also like the Bionic man charging out of elevators and crushing anyone who tries to subdue him. Yet there’s a side to him that’s fearful and childlike and it’s clear, in the end, that his father and mother must continue to endure their struggles and their abnormal lives with him by their side.

In Yorrick we are in the thick of a love triangle. The narrator is the the first man to fall in love with a neighbor called Catherine. The more he tries to woo Catherine, the less headway he makes. In no time, however, Yorrick, his new roommate, seems to win her over. The lovesick narrator feels hugely slighted. He’s brittle and warped from undue jealousy and bitterness and his emotions lead him to a drastic series of actions.

Darma’s magical storytelling manages to squeeze out my empathy even for the most disparaging character in his stories. He always gets me to suspend, willingly, all my judgement, even when I am appalled by the heinous conduct of some of his characters. In almost every instance, as the story progresses and devolves to its startling conclusion, the narrator is engulfed in remorse. But what’s to be done? How does a human being right a dreadful wrong?

It’s hard to miss the underlying wisdom in each of the stories even when the characters are at their most absurd or insane. I read all of the stories but one in the collection (I always stash one away for later) and wondered if the author was trying to make a point that all human beings have a choice, that we can choose to either act or react.

The author passed away before this elegant English translation saw the light of day in April 2022. Even though the Indonesian original Orang-orang Bloomington was published in 1980, a little after Darma’s time on a college campus in the United States, the translation of such a terrific collection would only appear after over forty years!

I close by noting that the first thing that struck me upon seeing a picture of the late Budi Darma was that he was a cross between the Dalai Lama and my own father whose stories and beliefs informed my book about his life. After reading Darma’s stories in his collection, I have absolutely no doubt that my father (as well as the Dalai Lama himself) would have wanted to meet this brilliant Indonesian writer with an empathetic soul and a delicate pen.

Hi Kalpana,

I enjoy reading your book reviews and wonder if you would give "Keshu - Climate change and a brave little fish" a chance to be read by your followers via a book review. Everyone who has read it so far has seen something different in it. Knowing how you write, and introspect, I'm curious how you would see it.

Link to its webpage: https://tinyurl.com/ms7h2732

Links to buy are: https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=MANjEAAAQBAJ

and http://www.amzn.com/B09TNM3GX1

Best,

Kavita Dorai, Author

For a literary tourist like me, this observation hurt: “They see the Eastern world as something exotic, as interesting because of its foreignness. To them, local color is immensely fascinating.” I mean, ouch. I’ll have to process this one a bit, but thanks for clonking me over the head with it.