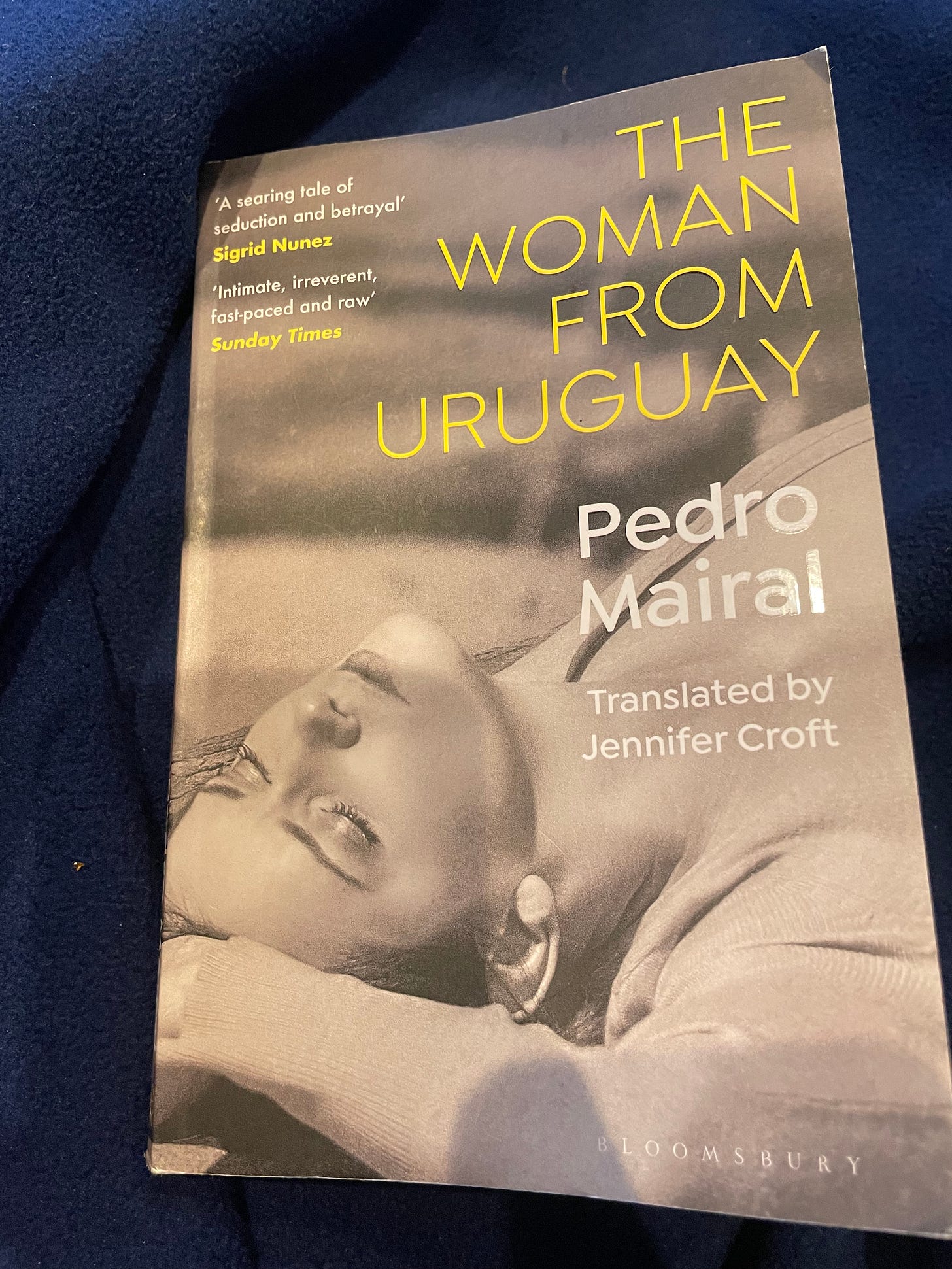

THE WOMAN FROM URUGUAY

Pedro Mairal's compelling tale is a story about a writer whose life was dictated mostly by his penis, not his pen.

I’ve been on the road for the last two weeks and, like Lucas Pereyra, the protagonist of the novel I chose to read over the last two weeks, I found myself feeling somewhat restless and unproductive. I was not doing what I was supposed to do in order to write my Substack post, yet I was, in fact, doing a lot. Unlike Pereyra, however, I didn’t drink myself silly or smoke pot or look for love in the wrong places. I was in a remote corner of western India, right by the India-Pakistan border, meeting the people of Kutch and seeing their lives up close.

I was doing so many other things that reading was not be a priority. Still, on balmy evenings in my home stay in the village of Bhujodi, I did make a beginning on The Woman From Uruguay by Pedro Mairal. Translated nimbly by Jennifer Croft from the Spanish to English, the novel takes a reader into the heart of a man’s midlife crisis.

Born in 1970, Pedro Mairal is an Argentinian novelist, poet and musician. A professor of English literature in Buenos Aires, Mairal has published more than a dozen books. In 2017, his novel La Uruguaya—the Spanish original of the book I was reading—won the Premio Juan Tigre which celebrates the best narrative work in Spanish in a given year. While reading him I realized why the work of some writers will stand the test of time. I waited with bated breath for Mairal’s commentary on love, marriage, parenthood and life. Consider the passage below on what can happen to a couple in a marriage.

It terrifies me the way couples become conjoined: same opinions, same degree of drunkenness, as if man and wife shared one bloodstream. There must be a chemical leveling that occurs after years of maintaining the constant choreography. Same place, same routine, same diet, simultaneous sex life, identical stimuli, shared temperature, incentive, income, fears, walks, plans.

The novel drips with the sadness of growing older and lacking motivation. It’s filled with many moments of reckoning that all of us have had at some point in our lives, the recognition that we may have made all the wrong choices. Lucas Pereyra is an unemployed 45-year-old poet and writer who has found a modicum of success. Yet he has not found the sort of stellar success that every writer aspires to and dreams of. When he receives an advance for his next novel, Pereyra knows what he must do. He must “smuggle” it into Argentina after having it deposited in a bank in Uruguay’s Montevideo; this way he can circumvent the laws in Argentina and make more on the dollar.

What we follow then, from start to finish, is his journey on that fateful day when he goes to the bank in Montevideo. Once again, however, we begin to see why success has evaded our protagonist. To make it big in life, what a human being needs, among other qualities, is the right blend of talent, wisdom, acuity and self-control; if any of these is missing, the outcome can be skewed. This one day in Pereyra’s life—the day when everything was going to be resolved and he would be left with all the time in the world to write his next big novel—turns out to be disastrous. It makes Roger Hargreaves’ Mr. Messy seem like a perfect candidate for a Rhodes scholarship.

The novel is brilliant in pacing and narrative power. We feel Pereyra’s angst all the way to the end. I have yet to read a work in which the interleaving of past and present is so artfully done that it feels effortless and natural for for the reader.

What I loved most about The Woman From Uruguay were the moments of reflection and self-flagellation. Here was a man who knew what he must do but had zero self-control or forethought. He was driven by a portentous collision of life circumstances—his libido, his insecurities, his lack of accountability and his grandiose writing plans—to do all the things that he probably should not. We were watching a man whose life was dictated mostly by his penis, not his pen.

My back was giving out on me, the roll of fat on my skinny-guy’s belly getting more prominent, stray grays on my head and my crotch, and then there was my dick that from one day to the next seemed to lean slightly to the right, like my compass had gone crazy and abandoned the north to point a little to the east, to Uruguay.

In Lucas Pereyra’s failings, I saw so many bits of me. I have no doubt that every reader will recognize himself, too. By the time Pereyra returns to Buenos Aires, we know he will begin to be on the mend somewhat. His body and his mind have taken a severe beating, after all. The scars he bears now, aside from his new tattoo on the shoulder, are justified. They have been a very long time coming. By the time the book ends, we know that he will live although it’s not clear just how well.