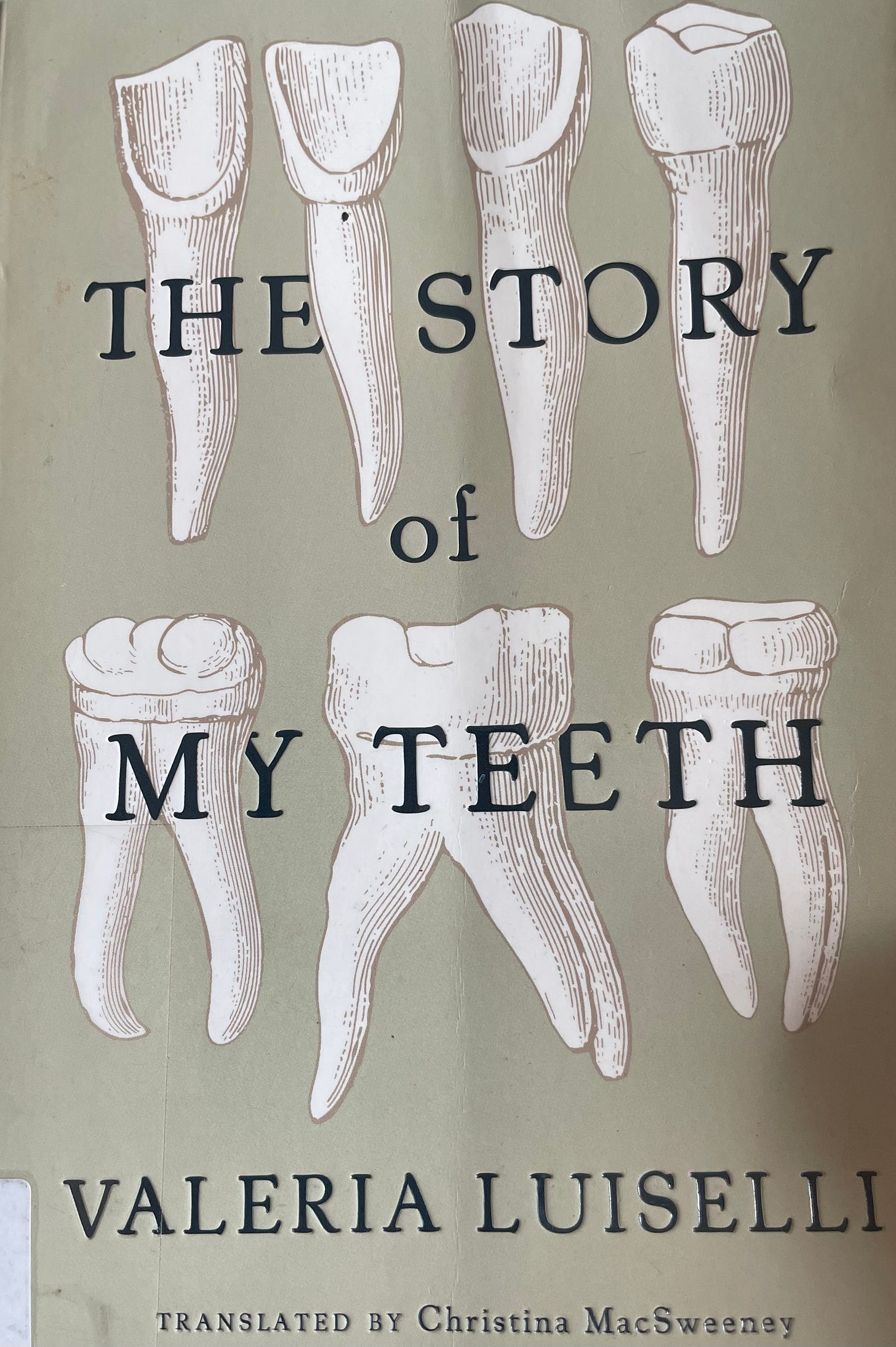

THE STORY OF MY TEETH

In this "collectively written" Spanish novel by Valeria Luiselli, we see the world through the sharp eyes of a Mexican auctioneer whose teeth were so bad he was called "Highway".

Valeria Luiselli’s novel is built imaginatively around something very close to my heart: My teeth. Just as my teeth have been the bane of my existence since I was an adolescent, his teeth become Gustavo Sánchez Sánchez’s nemesis in The Story of My Teeth.

Ugly as he is since birth, Sánchez is apparently the best auctioneer in the world, but no one knows it because he’s so discreet and will rarely ever open his mouth too wide. As the story opens we see Sánchez in a poorly paid security job until, one day, events lead him to new pastures. He learns that one writer came into a lot of money with his book that allowed him to fix his teeth. Sánchez puts himself on a path to his new set of teeth by establishing himself in the auction business until, one day, the auction actually leads him to two sacred rows of teeth that he will then make his own.

In the small glass box the auctioneer held high lay waiting for me the sacred teeth of none other than Marilyn Monroe. Yes indeed, the teeth of the Hollywood diva. They were perhaps slightly yellowed, I believe because divas tend to smoke. There was a feeling of tension and unease in the air when the auctioneer opened the bidding. Several ladies who had seen better days, including one of our lady friends, already had their eyes on them. A fat man in outdated clothes spread a wad of bills on his bar table and stood up to light a cigar, to intimidate us I think. But I dug in my heels and got them: the teeth—my teeth—went to me.

Our man Sánchez, aka Highway, now begins to lie through Marilyn Monroe’s teeth. After affixing those pearly teeth onto his gums, his entire life seems to undergo a dramatic change. Having acquired a tremendous amount of knowledge across what may be considered esoteric subjects, Sánchez becomes a man about town, a collector (of what most of us may consider garbage) as well as an art enthusiast.

In the novel, this consummate conman auctions off ten old teeth for a church benefit, narrating the most spellbinding stories for each tooth. Our protagonist is a man I’d love to have coffee with, for he, Highway, is "a lover and collector of good stories, which is the only honest way of modifying the value of an object."

The Story of My Teeth made me ponder all the objects I’d collected over the years that were now part of my house that, in a few decades, would hold symbolic meaning for my children and my grandchildren. Let’s ponder this for a moment: An object of daily use that we often value as almost worthless in the present day goes on to acquire untold value in a few decades. What makes this idea even more interesting is this human predilection to weave stories around such objects. Those stories then assume legs of their own as others retell them.

In the story, the brilliant auctioneer inflates an object's value by employing hyperbole, in what he calls "an elegant surpassing of the truth."

This meant that the stories I could tell about the lots would all be based on facts that were, occasionally exaggerated or, to put it another way, better illuminated.

Some of the most exciting passages of the book are in the words that tease out the value of an object. They are laugh out loud funny and oh SO smart. What made them so enjoyable for me personally were my own previous “encounters” with the illustrious personages parading through the pages.

As a student of literature, I’d so loved the essays of Charles Lamb (himself an antiquarian) but I had no idea that for years he’d been tormented by a tooth issue, just like I now am. This is how Highway presents Mr. Charles Lamb.

It would not be unreasonable to imagine that everything Mr. Lamb wrote—which was a lot and very good—was the product of the tortuous disposition of his teeth. He had a schoolboy stammer, and his writing was equally stuttering. He once wrote a stuttering letter to his friend Wordsworth saying, “I have just now a jagged end of a tooth pricking against my tongue, which meets it half way, in a wantonness of provocation, and there they go at it, the tongue pricking itself like a viper against the file, and the tooth galling all the gum inside and out to torture, tongue and tooth, tooth and tongue, hard at it, and I to pay the reckoning till all my mouth is as hot as brimstone.”

Eight hundred pesos for Lamb’s stuttering tooth! Who will open the bidding? Who will give me more?

While this is a fascinating book on art and the value human beings ascribe to objects, I’m not sure that it held my interest beyond the halfway point. For me, the most exciting part of the book was concentrated in the first half. Following that, it began to feel like a fantastic meal—for which I had paid dearly while making my reservation—that progressively churned my stomach a little and rendered itself a tad bilious. Perhaps there was a reason for its inability to feel whole somehow and engage me all the way to the end.

Originally commissioned as an exhibition catalog for Galería Jumex in Mexico City, this novel was written in collaboration with workers at a Jumex juice factory in Ecatepec. Luiselli would submit chapters for lecturers and readers at the university to read to the factory workers, who would then send recordings of their discussions back to Luiselli.

The English-language edition also features a chapter written by Luiselli's translator Christina MacSweeney, and as Luiselli explains in her afterword, Sweeney’s “Chronologic is a map, an index, and a glossary for the book, which both destabilizes the obsolete dictum of the translator’s invisibility and suggests a new way of engaging with translation; one that neither relies on bringing the writer closer to the reader—by simplifying and glossing the translated text—nor on brining the reader closer to the writer—by means of rendering the text into a kind of “foreign English.””

When I shut the book, I realized that I was bowled over by Valeria Luiselli’s mind. Quirky and choppy as her book felt to me, I’m in awe of Luiselli’s ability to pull from the treasure troves of what is clearly an unlimited curiosity about the world simply in order to spin a wild tale featuring characters from across the centuries that included Plato, Plutarch, G. K. Chesterton, Rousseau, Virginia Woolf and Jorge Luis Borges, among others.