THE SIKHS OF SINGAPORE

The tiny Sikh community of 13, 000 has been an invaluable addition to Singapore society. I spoke to an accomplished Sikh Singaporean who told me how Sikhs have flourished along with their island.

It’s odd that a good friend of ours, a Sikh gentleman in India’s Beas, should write to us on the very day that I had been thinking of him. I had just been pondering how fortunate it was that we had got to know Inderpal Narang and his wife, Sushil, when they lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. My husband and Inderpal had worked together closely for years; we had met socially, too, especially in the years before our lives became busy with our children’s activities.

On a family trip to the Golden Temple in Amritsar in the summer of 2012, we never got to enter the sanctum of the holy Harmandir Sahib. Just prior to that, my husband suffered a nasty fall and sustained multiple fractures. Our day thereafter was spent at the temple’s dispensary and at doctor’s offices around town. Thanks to the warmth and compassion of several members of the Sikh community in Amritsar, and to Inderpal’s resourcefulness in ensuring that we were well looked after, we went on to have a memorable stay in the week that followed.

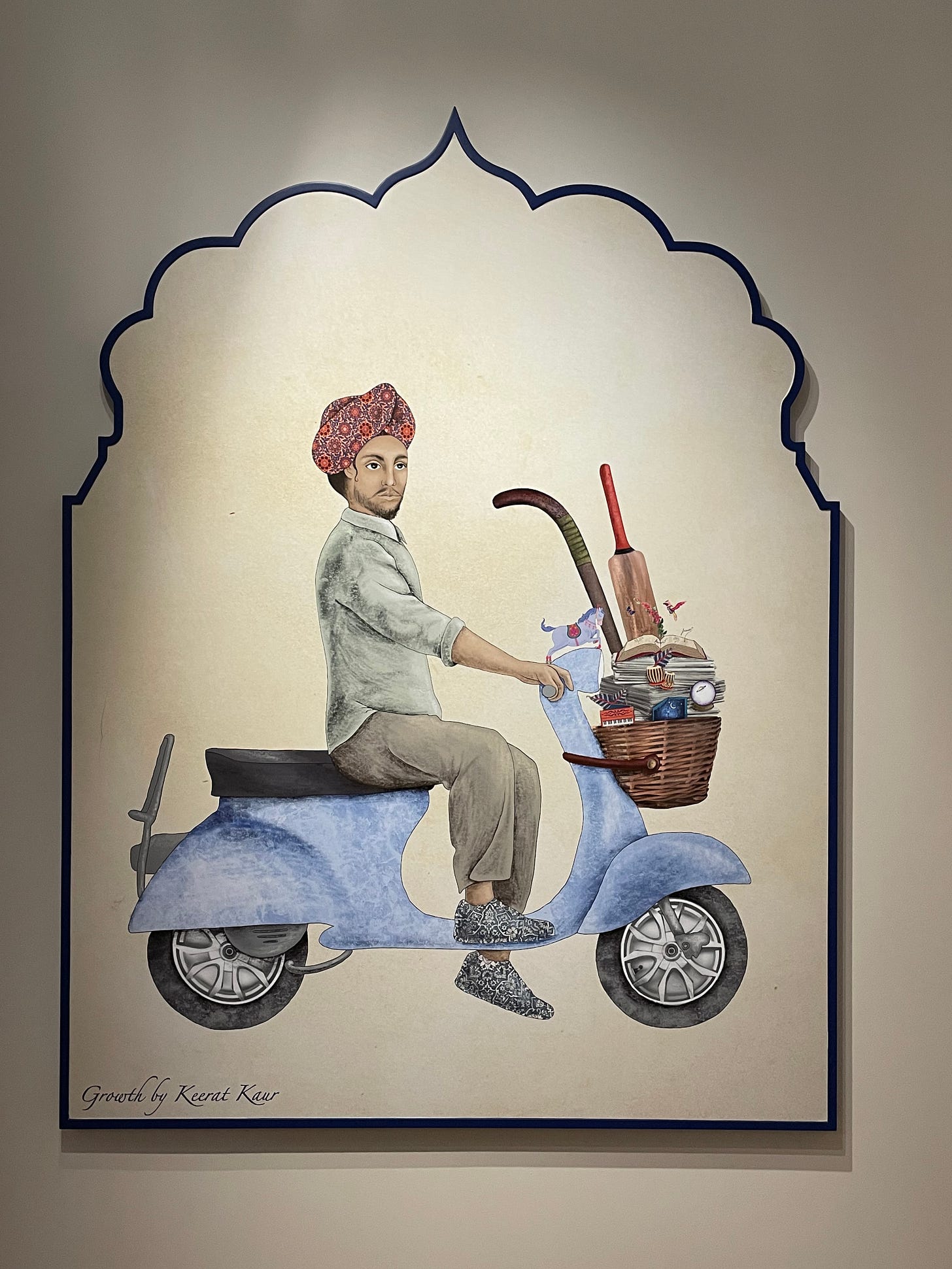

Our family experienced the kindness of the Sikh community that week and it made a deep impression also on our children. I was reminded of that generosity on the day I visited an exhibit detailing the lives of Sikhs in Singapore at the Indian Heritage Center (IHC).

It seemed so topical now, during the second wave of Covid-19 in Delhi. Even as hospitals ran short of beds and oxygen and the scarcity of supplies drove up the cost of medicines and oxygen, at least two Sikh gurdwaras had arranged an “oxygen langar” to provide free oxygen to the COVID-19 patients who needed it.

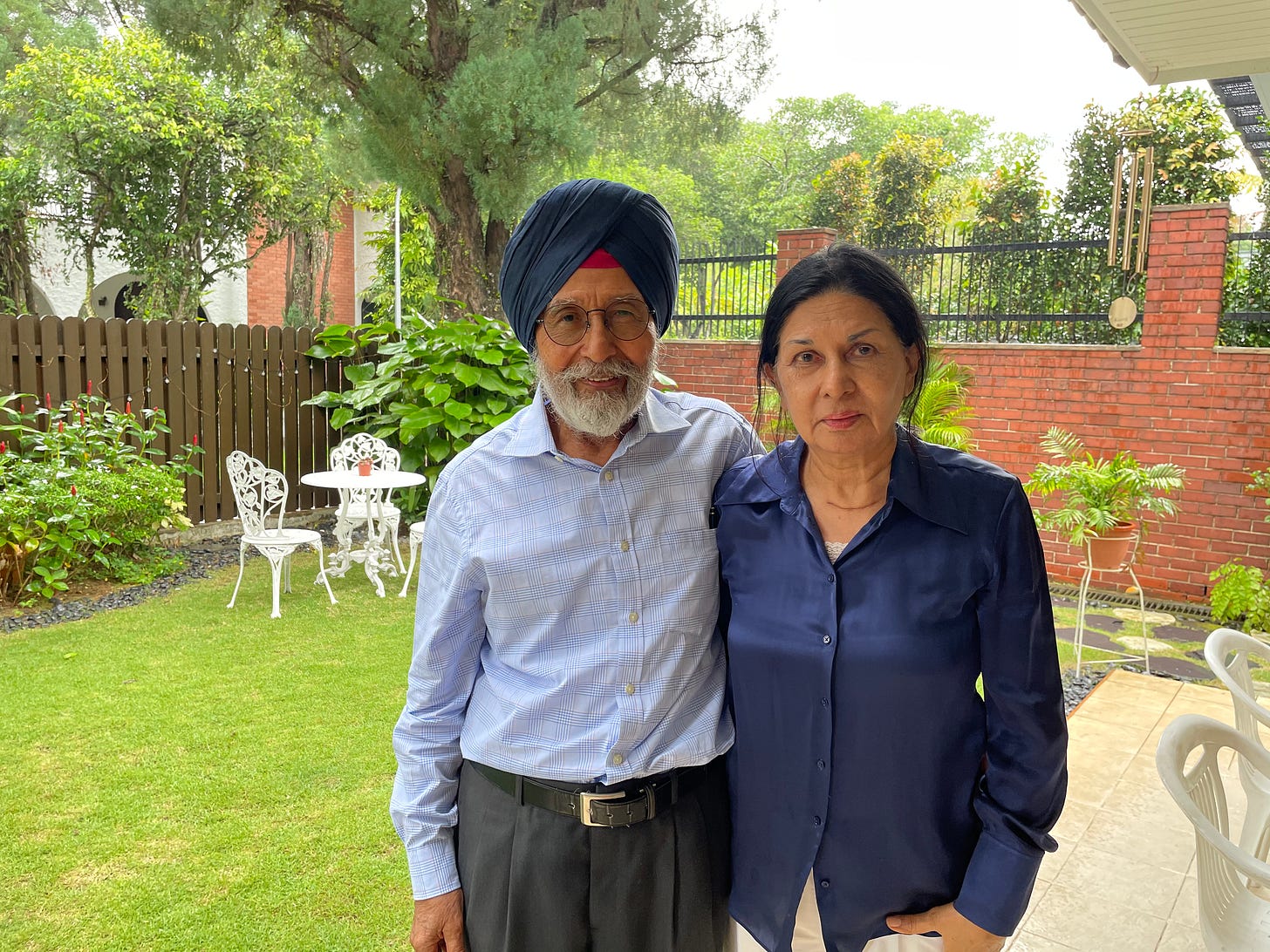

The day I sauntered through the displays at IHC, I observed an elderly Sikh gentleman who made his way through each section and listened keenly to each audio recording in the installation. At one point, my curiosity got the better of me and I walked up to him to find out what he thought of the stellar curation of Sikh life and contribution to local life. The gentleman beamed at me from behind his mask and his glasses—reminding me so much of my father in that moment—and told me that he believed it was indeed a thoughtful curation. Saying that, he hesitated for a few seconds before letting drop a small but important detail, that he and his family had also been featured in it.

Such serendipitous moments rarely ever happened to me. (Imagine meeting George Clooney as you’re watching Ocean's Eleven in an empty hometown theater, buttered popcorn in hand.) Naturally, minutes later, I was receiving a personal tour from the scion of one of Singapore’s respected Sikh families. Param Ajeet Singh Bal’s life had obviously been one of great accomplishment but I saw an abiding humility as he led me through some of the displays.

A few days later, I was at Mr. Bal’s villa in a leafy suburb of town, meeting his family. Over many hours on that visit, I sat listening to his life stories about his grandfather who arrived in Singapore in 1901, and about Sardar Tara Singh, his father, who went on to become a respected businessman and philanthropist. Mr. Bal himself graduated from Singapore’s elite institutions. He entered the Singapore Administrative Service in 1963, very shortly after Singapore gained self-government (prior to independence). In the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Environment, Mr. Bal worked closely with many top leaders in government and would go on to have an intimate view of Singapore’s journey from poverty into affluence.

Many times during our meetings, he told me he had been fortunate. His family had been wealthy even at the time of his birth. “That’s why during the Japanese occupation of this country, we could take a boat back to India,” he said. “Not everyone could afford that.” The story of most members of the Sikh community in Singapore involved a lot more hardship in the early years, I learned.

The first Sikh landed in Singapore because he had led an uprising against the British in India. Bhai Maharaj Singh was arrested in December 1849 by the colonial government, transferred out of the Punjab, shipped to Singapore and imprisoned at what was then called the New Jail on Outram Road. He died in prison in 1856. The story of why other Sikhs were brought into Singapore, other parts of Southeast Asia and to America’s Pacific coast calls for a short history of the British Raj in India.

In the 18th century, the Mughal invaders of the Indian subcontinent beat a retreat from the Punjab when they faced a strong resistance movement led by the Sikhs trained in warfare by their tenth and last leader, Guru Gobind Singh. He instilled in his people the tenet that people must fight, until their last breath, for the cause of justice. Despite the resilience of the Sikhs, internecine wars and threats from the surrounding territories—by the Afghans, the Marathas, the Gurkhas, the Rajputs—whittled down the power of the Sikh warriors.

A frail man, blind in one eye and scarred by small-pox, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, emerged as the last of the princes uniting the Punjab; he consolidated the Sikh Kingdom comprising of four provinces with a population of 3.5 million people. Spread across Lahore, Multan, Peshawar and Kashmir, Ranjit Singh’s court was cosmopolitan and secular. I’ve been reading stellar accounts of his vision and leadership; he enticed Americans and Europeans to work in his court and his military. During his reign, he lavished attention on art and fostered the growth of all religions.

In 1839, however, the death of this resourceful ruler altered the course of this region forever. Chaos ensued; ten years later, the British trounced the Sikh empire in the second Anglo-Sikh War. Their lives overhauled, the Sikhs were compelled to look at the opportunities that presented themselves: Recruitment in the British military; a career in the police force; many different career paths in the civil services in the colonies of the empire; an agrarian life; the odd job in lumber and construction. These would determine the course of Sikhs in different parts of the world.

Sikh soldiers, most often recruited from the Jat community in Malwa, thus became the face of the rapidly expanding British Army and they were dispatched promptly to strengthen the colonies: to Hong Kong, Yenangyaung (Myanmar), Canton, Singapore and other locations. They played a central role in every battle that ensued. Men of the Ludhiana Sikh Regiment served during the Second Opium War in China in 1860. Sikh units fought in the First World War as the "Black Lions", and decades later, they also represented the British Army during the Second World War in Malaya, Burma and Italy.

The fate of those left behind in the Punjab after British conquest was uncertain. By the end of the 19th century, the state suffered under British mercantilism; many Sikhs, with their agrarian experience, emigrated to the United States to work on farms in California. Sikhs who were not a fit for the army were recruited into the Sikh Police Contingent by the government in Singapore; for over sixty years, these turbaned Sikhs were part of the police force.

I learned that only Khalsa Sikhs—orthodox Sikhs who had been initiated into the behavior code and dress code of the Khalsa tradition—under the age of 25 (minimum height of 1.68 metres and a chest measuring 84 cm) were eligible at the time.

“It is when I make sparrows fight hawks that I am called Gobind Singh. It is when I make lions out of wolves that I am called Gobind Singh. It is when I make the lowly rise that I am called Gobind Singh. It is when I make one fight a hundred thousand that I am called Gobind Singh.”

~ Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708), who exhorted his followers to be valiant and fight until the end. He was the tenth and last spiritual leader of the Sikh religion.

As Punjabi and Urdu speaking migrants flooded into Singapore in the late 19th century, interpreters, translators, notaries and clerical staff were needed; Sikh graduates sought jobs in Singapore and Malaya when they could not find jobs in India. Other early settlers started a dairy farm or a commodities trading business. Sikh men who did not qualify for any other professions often filled the position for a security guard or “jaga” (a Malay word for security guard).

In the early 20th century Singapore, the Sikh security guard stood sentinel at warehouses, factories, offices and educational institutions. Perhaps as a relic of this outmoded way of life, even today I can see a resplendent Sikh gentleman fiercely standing guard at Raffles Hotel. The notion of Sikhs as guards has permeated into the soil in Singapore. In some Chinese burial grounds, Sikh guards carved in stone still stand in attention, a testament to their extraordinary prowess in protecting people, even in the afterlife, a fact of Singaporean life that led to the stereotyping of this community for years.

During the second half of the 20th century, some Sikhs entered the retail business. Mr. Bal’s father’s story was singular. A brilliant man, Sardar Tara Singh, born in 1903, studied at the Anglo Chinese School in Singapore and qualified as a marine engineer. Soon he realized that expanding his father’s retail business into household goods and furnishing would be more lucrative and fulfilling. Tara Singh became a force among Sikhs, contributing to the Singapore Khalsa Association, and establishing schools and places of worship for his community. Sikh Singaporeans, who make up just about 15, 000 of the total population today, form one of the smallest ethnic groups in Singapore. Yet they are known for their largesse; giving back is a core principle of the Sikh faith.

At the exhibit, I came across a few other institutions begun by members of the Sikh community. I’d heard, of course, of the name “Thakral”. A friend who works for the company, says that the gentleman who launched Thakral Brothers in 1952—he is 88 years old—still shows up at work every day. As Mr. Pal explained to me, Sikhs work very hard. The work ethic is engraved into the belief system of Sikhism. These character traits—integrity, hard work, loyalty, community consciousness—have stood them in good stead, whether the individual was in the army, the police, the administrative services or in business. Sikh Singaporeans are now lauded for their success.

“But it was not always so, let me tell you,” Mr. Bal cautioned, saying that life in the early years of Singapore were hard for ethnic communities. Singapore was the hotbed of racial riots in the sixties and almost everyone felt the blowback of racist sentiments. He praises Singapore for its conscious effort in attempting to strip that sort of meanness from the nation. The prior attribute of “jaga” isn’t wielded anymore as an epithet in this country. He believes Sikhs in Singapore feel contented and relaxed because their community is respected. He says there is a sense of security among his people in Singapore even though elsewhere in the world racist sentiments are on the rise.

Mr. Bal told me about something that happened to him recently. One evening when he was out on his walk, a voice called out to him using a slur. It took him by total surprise but he pretended to not notice. Most spats continue when we react, Mr. Bal pointed out. He said he believed that we could not erase all the negative phenomena in the world but we could control just how we reacted to them. He credits the Singapore government with being adamant about its expectations of social norms. If inter-racial harmony is not a given, it can be cultivated by a people of a country over time.

Several times during the few hours at his bungalow, Mr. Bal stopped to introduce me to yet another family member who happened to walk in during our conversation. His wife, Naresh, would not let me leave the house without feeding me a meal. On the menu were phulkas, rajma, pulao, raita, pumpkin curry and fruit, prepared and served artfully by their Indonesian helper, Sangha, who, according to Naresh, knew the mood of every family member so well. When I went in at 10.30 AM, I had no idea that I would leave many hours later, after a whopping lunch. Having known Inderpal and Sushil, I should have guessed and offered to visit at tea-time instead.

Nicely documented, Kal.