THE MUSICIAN WHO WAS TONE-DEAF

I didn't pick up this book during my long flight was because I blazed through Succession's final season, like a maniac. Upon landing, this powerful German novel became a serious cure for jet lag.

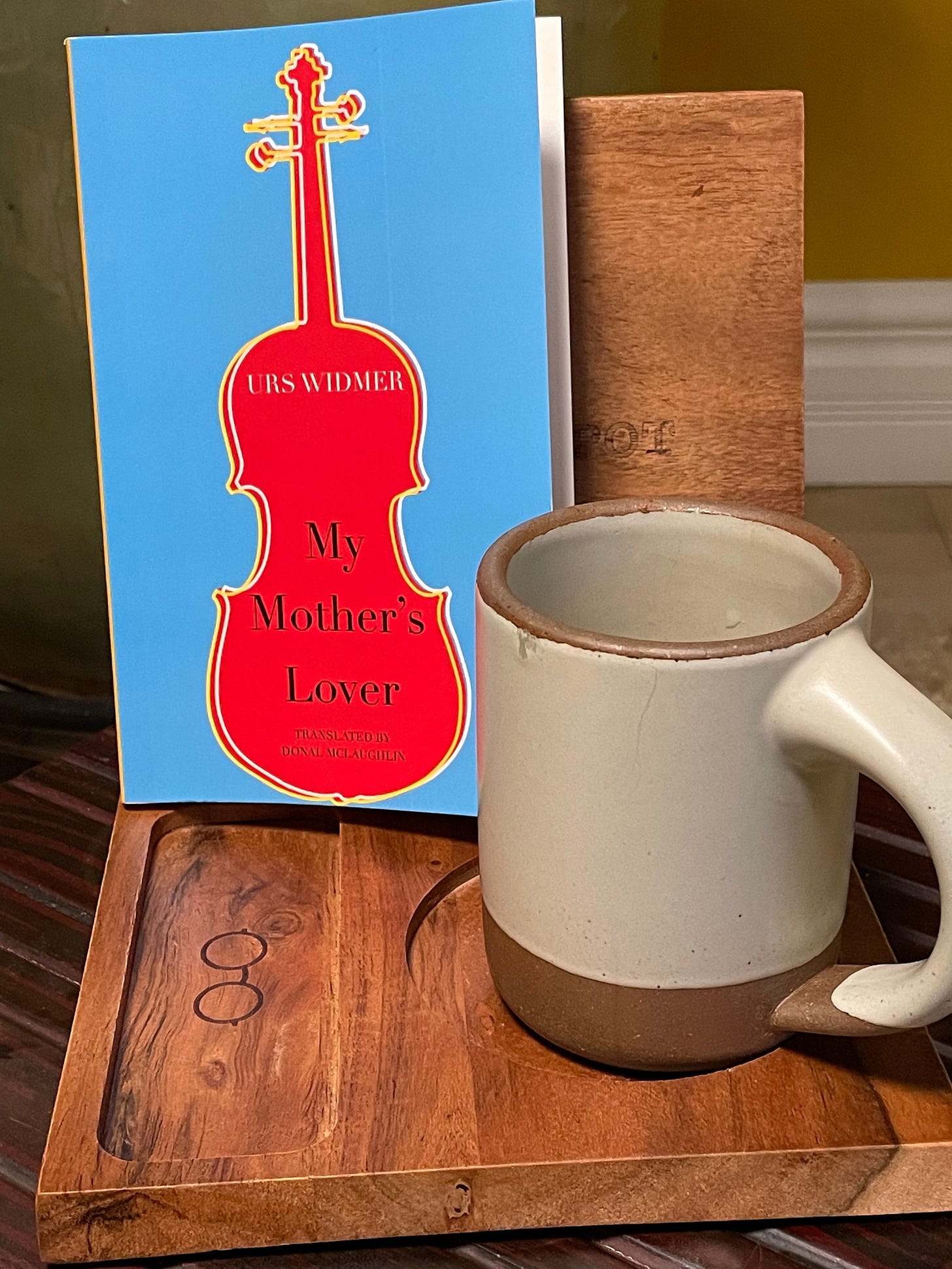

My Mother’s Lover is a warning to all human beings to refuse to be obsequious, rheumy doormats to others. Written by the late Swiss writer Urs Widmer, books like this tend to justify this weekly project of mine. Here is an exceptional novel in which we keep watching the power of music build the career and hubris of one man while steadily unraveling the life and mental well-being of a woman who loves him so much she cannot see through the miasma wrought by his persona.

—My mother loved him all her life. Not that he noticed. That anyone noticed. No one knew of her passion, not a word did she ever speak on the subject. “Edwin,” mind you, she would whisper when she stood alone at the lake, holding her child’s hand. There, in the shade, surrounded by quacking ducks, she’d look across at the sunlit shore opposite. “Edwin!” The conductor’s name was Edwin.

Reading Widmer’s words—and those of translator Donal Mclaughlin—will have me looking for translations of his other works. Ever since I discovered that My Mother’s Lover was a true story, I’ve been wanting to know more about whose story this actually was. Who was the composer whose life story this is? Who' is the lover? There’s little written, in the English universe, at any rate, about the background to this work. It doesn’t matter, however, for there’s so much to celebrate in this perfectly paced story—from the opening line, to the first page, the keen dismantling of character, the closing paragraph and the book’s captivating cover.

My Mother’s Lover is told in first person by the son. The story of his mother Clara spans over eighty years, beginning just before the Black Thursday in 1929, when she is about 20 years old. While Clara grew up with her father in Zürich in luxury, we discover, later, after the long-widowed father dies, that he was mired in debt and living way beyond his means. From a life of chauffeured cars and liveried servants, Clara finds herself in penury, settling her father’s debts and, subsequently. losing her childhood home. This is when the title character of this novel enters Clara’s life. While attending concerts with her father, she had been obsessed by the work of one Edwin, the man who would go on to become one of the most famous conductors of all time. As she contends with her downsized life, Clara starts to work for Edwin and his Young Orchestra, becoming its life blood. Clara becomes Edwin’s secretary of all things (which includes his libido).

When Clara gets pregnant with their child, Edwin wants her to get rid of the baby; she doesn’t imagine, in her wildest dreams, that this signifies the end of their relationship. When Edwin makes the appointment to get their child aborted, it was as if it were yet another pesky todo on the pre-concert list of the Young Orchestra.

Edwin had set the appointment up. In the evening, it was after seven. The doctor was alone. No assistants. He was very polite, very proper, asked my mother to sit on the examination chair. The cellist held my mother’s hand. Afterwards, they traveled home, back to the room that had previously been Edwin’s, where the child that had just been killed had been conceived.

Clara is so deep in the well of patriarchy—groomed by her jerk of a father to be voiceless—that no injustice or insult unleashed by her douchebag of a lover can be dreadful enough for her to jump out and scream STOP. One day, Edwin marries the rich daughter of an industrialist, and Clara, who is devastated, ends up marrying the narrator’s father .As the tale progresses, we also learn that Clara is the perfect housekeeper, especially when she is not suicidal or seeking treatment for her depression.

It’s impossible to pin down exactly why a particular book succeeds in telling its tale well to a majority of its readers. The stories that grab me in the first line are winners when their turns of phrase is matched by their ability to sustain the tension in the plot. This invariably means that novels need to be tightly spun, that the pacing is meticulous and that the forward momentum is evident in every paragraph of the work. I’ve seen some of the longer novels juggle these elements masterfully as well; Maria Judith de Carvalho’s Empty Wardrobes, Javier Marias’ A Heart So White and Dino Buzzati’s A Love Affair balance craft, storytelling, exposition and a sense of place over some 400 fiery pages.

I couldn’t put this book down. That’s saying a lot because I tend to come to judgment rather quickly about a book’s potential. This weekly assignment has been invaluable for that reason. It has taught me patience and revealed that every writer comes with different gifts. One of Widmer’s great gifts is pacing. He is not a master craftsman of the greatest sentences, yet he is able to bring a place to a page with unusual efficiency.

I loved how he skitters over several years by showing us how Clara navigates the years after Edwin marries someone. Clara checks herself into hospitals for electric shock therapy used for the treatment of depression. When she became well, she returns home to be with her son. In one section, Widmer juxtaposes the private and the public life in what makes for a glorious passage.

Invisible, in the distance—invisible for the moment—was the war. (Hitler had ravaged Poland.) My mother put her case in the bedroom, hung her coat in the wardrobe, put on her oldest dress and her mountain boots, and went into the garden. She felled the lilac trees and the whitethorn and ripped out all the narcissi, tulips, daffodils, irises and cowslips. With a spade, she turned over the flower garden she’d just cleared—a bare field now, from one horizon to the other—without any help. There were no men anymore. She broke the clods of earth up with a hoe, throwing all the stones—a great many, countless, the field was very rocky—on a pile that soon became a mountain. She raked the broken-up clay, again and again, and then once more. Until it was grainy; flour-like almost. (At Dunkirk, Hitler hounded the British into the sea.)

Here is a work that shows us how human beings, even the ones with the keenest ears, and those who, by dint of their careers, must be the most sensitive people on earth, end up, oddly enough, being the opposite. Edwin was one of the greatest musicians alive. Yet, he couldn’t hear the refrains in his real life because he was dissonant, insensitive, and self-absorbed. He was tone-deaf except when he conducted. If he were a real person, I might have had him dropped into Washington State’s Snoqualmie Waterfall (picture below) in January when everything congeals into shards of white and blue ice.

—Later, I sat in front of the TV for a few hours and watched the special tribute broadcast to mark Edwin’s death. The stations of his life. His trials and triumphs. “One of the century’s most important figures.” I saw Edwin with Bartok, Edwin with Stravinsky, Edwin with the young Queen of England and, at one point, as the camera panned over the Stadthalle audience, I saw, at the center of the balcony, —from far off, and for just a fraction of a second—a shadow that may well have been my mother.

Have you seen Maestro on Netflix? Similarly absorbing portrait of a great musician and the lives he impacted for better and worse. Riveting imo. It will be interesting to see how Bradley Cooper and Carey Mulligan fare in the Oscar scrum. I can’t remember two more brilliantly rendered performances. And you don’t have to read anything!