THE MISSED OPPORTUNITIES OF A LIFETIME

It will take me a few more days to piece my heart back together. This novel made me mull over my own unformed expectations of love and partnership.

“This intimacy came from thinking alike; in truth, it came from accepting one idea of an idea while preparing to pay the price demanded by the other. But isn’t this how souls come together, by holding another’s every idea to be true and making it their own?”

Madonna In A Fur Coat fell into my hands at Istanbul airport last Saturday. I read one part of it on the thirteen-hour flight back to San Francisco; the latter half I read while fighting brain fog from jet lag this past week. I’d spent two weeks in Bulgaria and Turkey with whacky friends and their eccentric husbands. Vacations like that can plant a cumulonimbus cloud over one’s head for days. What continued to feed that cloud was this Turkish book published in 1943 by Sabahattin Ali who was born in Bulgaria and raised in Turkey.

Translated to flow like the smoothest tamarind rasam on a rainy day—kudos to translators Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe—Madonna In A Fur Coat evokes the comfort food from South India, shimmery and light on top while so much of goodness lurks in its depth. This novel has been one of Turkey’s best selling books of the last many years, ringing in more sales than works by Turkey’s Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk or by the popular British-Turkish novelist Elif Şafak.

It’s a simple love story. Of all of Ali’s novels, this one went unappreciated by his contemporaries while he lived. According to this review in The Guardian, this book has garnered much fame and love in recent years because “it refuses the traditional gender roles that Turkey’s president seems hell-bent on enforcing.”

It’s especially relevant this Sunday morning, a few hours after Turkey’s elections to determine if Turkey’s authoritarian President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will continue to have sway over his country. During his reign, Erdoğan has been vindictive towards writers. Decades ago, writer Sabahattin Ali was jailed, too, several times, in fact, by another leader of a very different stripe—reformist Mustafa Kemal Atatürk—who espoused liberal policies. It is during his rule that Sabahattin Ali is believed to have been murdered by state security officers, in the year 1948, as he tried to flee his country.

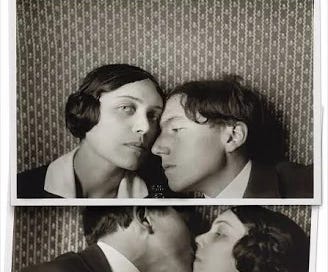

Like Ali himself, the protagonist in this novel, Hatip zade Raif, finds solace in the city of Berlin in the 1920s. Raif is a shy young man who happens to be a gifted artist; he hails from Ankara where his father is a wealthy businessman. Raif has been sent to Berlin to learn everything he can about the manufacture of soap so that he can cart the technology back to his father. For a young man like Raif, Berlin is brimming with possibilities but he is listless and uncertain about his future until one rainy evening when he walks into a museum. The world reels around him even as Raif falls inexplicably in love with a woman inside a painting.

“I saw in her echoes of Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil’s Nihal, Vecihi Bey’s Mehcure, and Cavalier Buridan’s beloved. I saw the Cleopatra I had come to know in history books, and Muhammed’s mother, Amine Hatun, of whom I had dreamded while listening to the Mevlit prayers. She was a swirling blend of all the women I had ever imagined.“

The work is a self-portrait of a woman called Maria Puder. Raif is deeply in love with her well before the smoky apparition in the painting walks out of the portrait—and straight into his life one day.

To our deep dismay, however, Raif is not trained to embrace happiness wholeheartedly. We don’t know just yet that he’s a wuss who needs a GPS lady to direct him even inside a salad bar.

“Ever since boyhood, I’d feared wasting any happiness that came my way. I’d always wanted to save some of it for later. This had caused me to miss many opportunities. Even so, I’d always been reluctant to wish for more, lest I frighten away my good fortune.”

This novella raises all the questions we typically snuff out as we go about our daily lives. It reminded me of my husband’s tepid response to a question about his life when he underwent a Doppler test some three decades ago in India. When asked how he would quantify the happiness level in his family life, he rated it a 5 out of 10. By the time the day was done (and the poor man had confided that number to me), his happiness quotient was a 0.3 on 10 because his partner, yours very truly, was simmering with resentment. I do believe, however, that happiness ratings are as unquantifiable as they’re subjective.

Putting my grievances aside, I believe it takes many qualities from partners in a relationship to guarantee each other a daily kind of contentment—one in which commitment and expectation, entitlement and kindness, humility and conceit, and levity and gravity, dance an unchoreographed tango. Finding and safeguarding personal happiness also takes intuition and courage. It takes spine. It’s the distinct lack of spine and steel in one person—namely, Raif—that causes the love boat in Madonna In A Fur Coat to capsize.

I suppose very few will agree with me on my reading of this novel. Almost every review I’ve read seems empathetic towards Raif. My only empathy towards this man is with respect to how his parents, in particular, his father, ill-treated him and suppressed his voice all his life. Without giving too much away of this fantastic and spell-binding novel, I’d like to say that nothing prepared me for the realization, by and by, that Raif’s spine was really lego-fitted from mung-bean noodles. (Note that these noodles are brittle when dry, and slimy and soft when drenched in hot water.) Oddly enough, I know I did in fact feel a deep empathy for Raif when I met him close to the start of the novel.

It’s impossible to not be haunted by the older Raif Efendi (Efendi being a term of respect in Turkish, a title of respect, especially for government officials). He is a weary, middle-aged father and husband. We glean later that it’s at least a decade after his return from Berlin. Raif is taunted in the office even when he is good at his work. At his home he’s bullied by his wife, his children, his brothers-in-law and his sisters-in-law. The money he makes feeds the entire joint family and he’s always falling sick and absent from his work. He’s depressed for reasons we do not yet grasp and it’s not just mildly irritating to watch an obviously gifted gentleman serve as everyone’s doormat in just about every interaction. What turns out to be a missed opportunity in reacting in a timely fashion to the people around him, we realize later, is simply one more in a neon-signed cavalcade of missed opportunities. If Gulliver had visited a country called Yet-Another-Missed-Opportunity, our man Raif would be its Crowned Forever King.

Exasperated as I am with Raif, I just loved Madonna In A Fur Coat. It will take me a few more days to piece my heart back together. This novel made me mull over my own unformed expectations of love and partnership. The book’s diatribe against the systemic patriarchy in our societies is as topical and as relevant in 2023 as it was in 1943.

The quality of love between Maria Puder and Hatip zade Raif is untrammeled by societal definitions of gender. Perhaps on account of its clarity, it’s also the kind of love that was doomed from the start. The finest things in life are too fragile to last.

“Maria Puder had taught me I had a soul. And now, overcoming a habit of a lifetime, I could see a soul in her. Of course, everyone else in the world was similarly endowed. But most would come into the world and leave it without even knowing what they had missed. A soul only came forward when it found its twin, when it felt no need to rely on mere words to explain itself… It was only then that we truly began to live—live with our soul. At that moment, all doubts and shame could be set aside. All rules could be broken, as two souls joined in embrace. All my inhibitions had disappeared. All I wanted was to pour out my heart to her, the good with the bad, the weaknesses with the strengths, holding nothing back, baring my soul. I had so much to say to her…enough to fill a lifetime.”

In closing, I’ve got to say that the sweetest objects of my life have entered my universe from airport kiosks: An ikat stole from Bangkok airport; a silver and terracotta Lord Ganesha from New Delhi’s swanky terminal T3; a three-strand, graduated ruby necklace on a jaw-dropping sale at Chennai airport. None of these, however, has been more precious than the discovery of an unknown voice from a faraway land that had the power—both to discombobulate and to teach.

I loved this piece and can't wait to get my own copy of this book to read. I love how you described the "unchoreographed tango" we dance every day of our lives, stepping on toes sometimes, achieving an ethereal grace and lightness of foot in all-too-rare moments, those moments that keep us going, that don't make a total mockery of our dreams and hopes. Thank you for this wonderful review!