THE EXPERIENCE OF THE OTHER

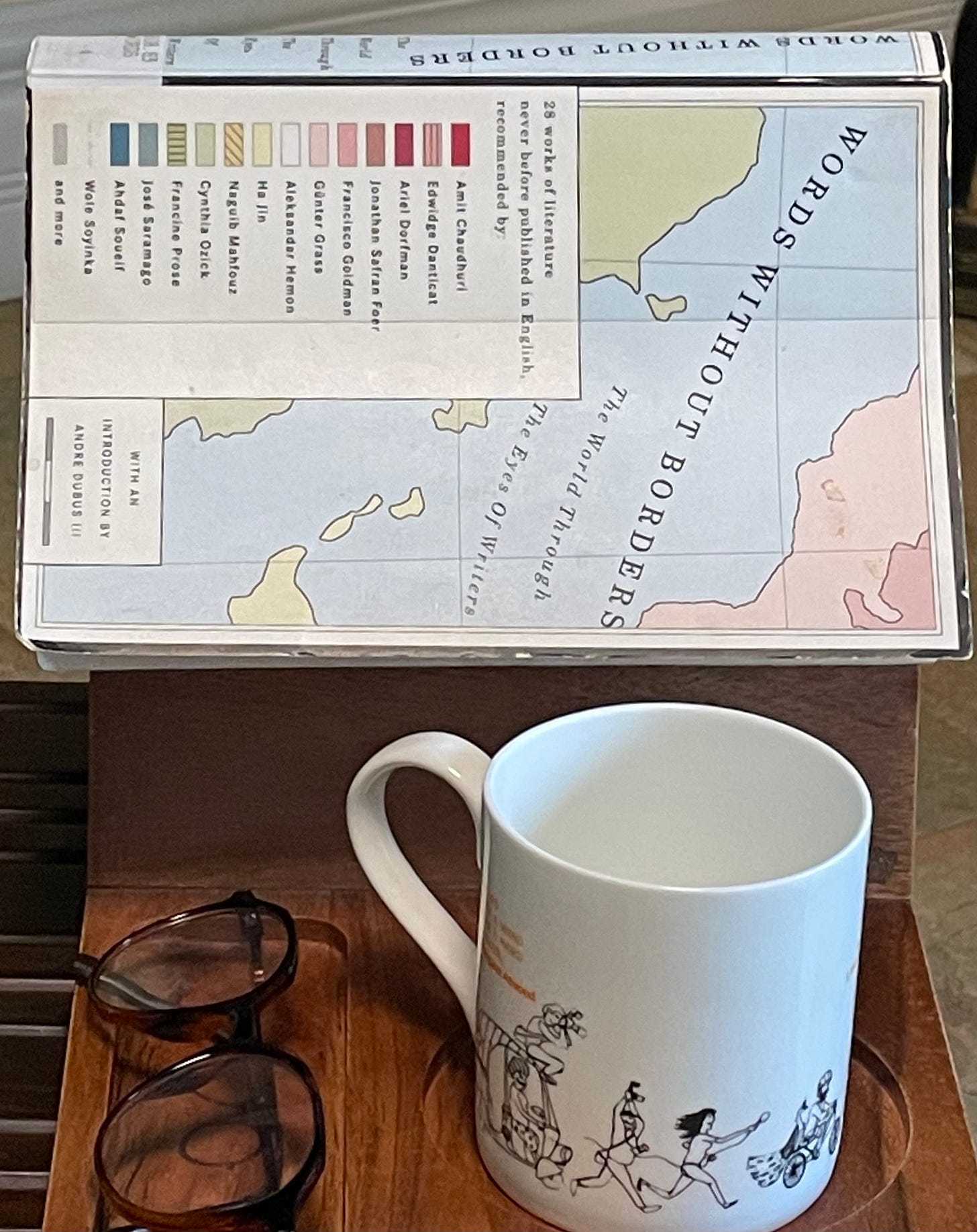

I'd been trying to express what I've gained in 24 months of reading, weekly, a book in translation when I happened upon this stellar collection of stories from many world languages.

If I had to buy all the books I write about week after week, I’d run up a gigantic bill. The man who shares our shrinking space with me will not be pleased. As it is, this retired gentleman mentions on and off that our home office has no room for his stuff even though his career award photos adorn all my office walls. For those reasons, when I’m looking for something to read for LETTERS FROM EVERYWHERE, I first look in the shelves at the Saratoga library. Some of my most enjoyable reads landed on my lap because I combed through the library catalogue.

Works like the collection I picked this week make us sit up and take notice of the world of words outside the English language; they also drill into why translations are important. In his perceptive introduction to the collection, novelist Andre Dubus III uses an expression that became the title of my post. They resonated with me because that’s what translations do, at least for me, in ways that books originally conceived in English often cannot.

There are twenty-eight stories in this collection and each one has been translated for the first time for this literary collection from Words Without Borders, “the home for international literature.” Every story is introduced by an illustrious writer and reading each introduction before reading the work was a wonderful exercise in itself.

I did not manage to read even half the stories in the collection and I know I’ll have to return to the other stories on another post. Work for my book and an upcoming trip to the far east have taken up a lot of my time in the past few weeks. Still, I managed to dedicate the early morning hours to reading selections from Words Without Borders.

Amit Chaudhuri introduces The Scripture Read Backward by Parashuram. In this story (translated by Sukanta Chaudhuri), the author places us in a Europe that has been conquered by India. British schoolboys—named Tom, Dick, and Harry—draped in a Bengali dhoti sit in pathashalas. They study how India, particularly Bengal, has brought order to a fractious Europe; the Mediterranean is now called Meti Pond and Switzerland is Chhachhurabad, and so on, in a systemic and incomprehensible name change that suits the whim of the Indian imperialist. Furthermore, newspapers feature facial powders to darken the skin of Englishwomen; and a growing British Home Rule movement puts up resistance to the propaganda of the Bengali empire.

The cotton fabrics of India have destroyed your renowned linen industry. Fie, fie, whose garments do you wear? They conceal your nakedness but not your shame; they keep out the cold, yet you shiver as you wear them. Your finest breeds of cattle have been exiled to India, where Hindus and Muslims fatten in concord on their milk, curds and ghee.You are forgetting the taste of beer and whiskey, while Indian hemp and opium slowly take possession of your brain.

Need I say more? The empire strikes back and how! Collections like this also enlighten us about many odd corners of the world that don’t normally enter our radar. I loved a German tale called The Fish of Berlin (translation by Susan Bernofsky). Written by Eleonora Hummel and introduced by Günter Wilhelm Grass, it’s a quiet story about the interaction between a granddaughter who wishes to bait her grandfather about his past and a heartbroken grandfather who doesn’t wish to take the bait because he doesn’t want to revisit his hoary past. Reading this story educated me about a community of Germans who suffered under the hands of Russians during the world war. In August 1941 the Soviet government ordered ethnic Germans to be deported from the European USSR. By early 1942, 2.4 million Germans had been banished to Kazakhstan, the Urals, and Siberia .

Some stories needed more homework such as The Day in Buenos Aires by Jabbar Yussin Hussin. The author is introduced to us as “belonging to the oldest literary community in the world,” for he’s from Iraq and it was one of his ancestors who made the first rudimentary marks on a clay tablet that would become a precursor to the epic of Gilgamesh and all the narratives that have followed.The Day in Buenos Aires (translation by Randa Jarrer) is conceived as a response to Averroes’ Search by Jorge Luis Borges. I went in search of this story by Borges, of course, and ended up enjoying that more than The Day in Buenos Aires. I’m yet to appreciate the thrust of both the works, however, and will be thrilled if my readers will enlighten me after reading both.

If there’s one story that everyone must read from this book, it’s The Uses of English by Nigerian Akinwumi Isola (translated by the author himself). I laughed out loud so many times while reading this hilarious work that I’m now going to be looking for more of Isola’s work. I’d like to see this story dramatized—the author is obviously a gifted playwright as well—and I’m already imagining how it will resonate with just about everyone in India. Please take the time to read this scintillating story and write your thoughts in the comments section!!! The story of the supposed might and heft of the English language is packed into this dynamite of a short story in the Yoruba language.

In direct contrast to the Yoruba story wasVietnam. Thursday., a Norwegian short story, that seems especially poignant as I get ready to fly to Vietnam in a few days. Vietnam. Thursday. brought into sharp focus the struggles of that nation over 120 years (longer if we consider the slow French occupation lasting several centuries). In this story by Johan Harstad (translation by Deborah Dawkin and Erik Skuggevik), we watch a woman in her doctor’s office.

Imagine that you pull the edge of a piece of paper swiftly across your eyelid. It hurts, doesn’t it? Just the thought? Now imagine that you bite hard on an uneven steel paper clip, scrape it across your teeth, grind at the enamel until the metal sends shivers over the nerves of your teeth. It hurts. Try to bring this word to mind: Vietnam.

Does it still hurt?

No?

It ought to. It certainly ought to. Perhaps that is the difficulty. Try to imagine that you pull your underclothes down, that you take one of your testicles, the left one, from your underpants, that you come up to the table’s edge, and carefully place it down. And that you lift the hammer, and strike. With—All—Your—Might.

That’s how it feels.

She says it every time. That’s how it feels.

Some stories are hard to read once more and I put this brilliant short story in that bucket. At a certain point in the story, we begin to see how doctor and patient actually converge in a transcendent moment of healing and agency.

Finally, I’d liken reading in translation to an experience I had when I visited the stepwells in India’s Gujarat. It’s one thing to look at a stepwell from the outer fringes of it. The first time we walk up to a stepwell, the panorama is mind-blowing; when we go down, however, the immensity of the enormous world of the stepwell rushes in and transports us into a world we must imagine anew.

I experienced the same feeling inside Kaymakli Underground City in the Central Anatolia Region of Turkey. It’s a descent of about five storeys and on every floor we found ourselves negotiating our way through a maze of small spaces. Soon enough we were comfortable inside that world. We began to discover sconces, lookouts, resting spots, broken friezes, and other features we’d never see anywhere else.

For me, entering the world of work originally conceived in another language offers exactly that intense experience, for it’s an entirely different view of the world, just the way I feel when I’m deep inside an underground city or a stepwell. I hope this post resonated with you as much as reading Words Without Borders did with me. As I sign off, I’d like to say that for the next few weeks, I’ll be a little erratic with my Sunday posts. I’ll be writing as I’m traveling.

Kalpana where would we be without you to pull these gems off the shelf in the Saratoga library? You’re like a spice trader returning from foreign lands with books rather than turmeric. Love the idea of this international sampler (in translation) and I’m adding it to my library now. Many thanks for another great find!

This sounds like a wonderful collection! I'm happy to find it in my university library and am looking forward to reading it. Thank you for the recommendation. :-)