THE CONTINUAL SORROW OF WAR

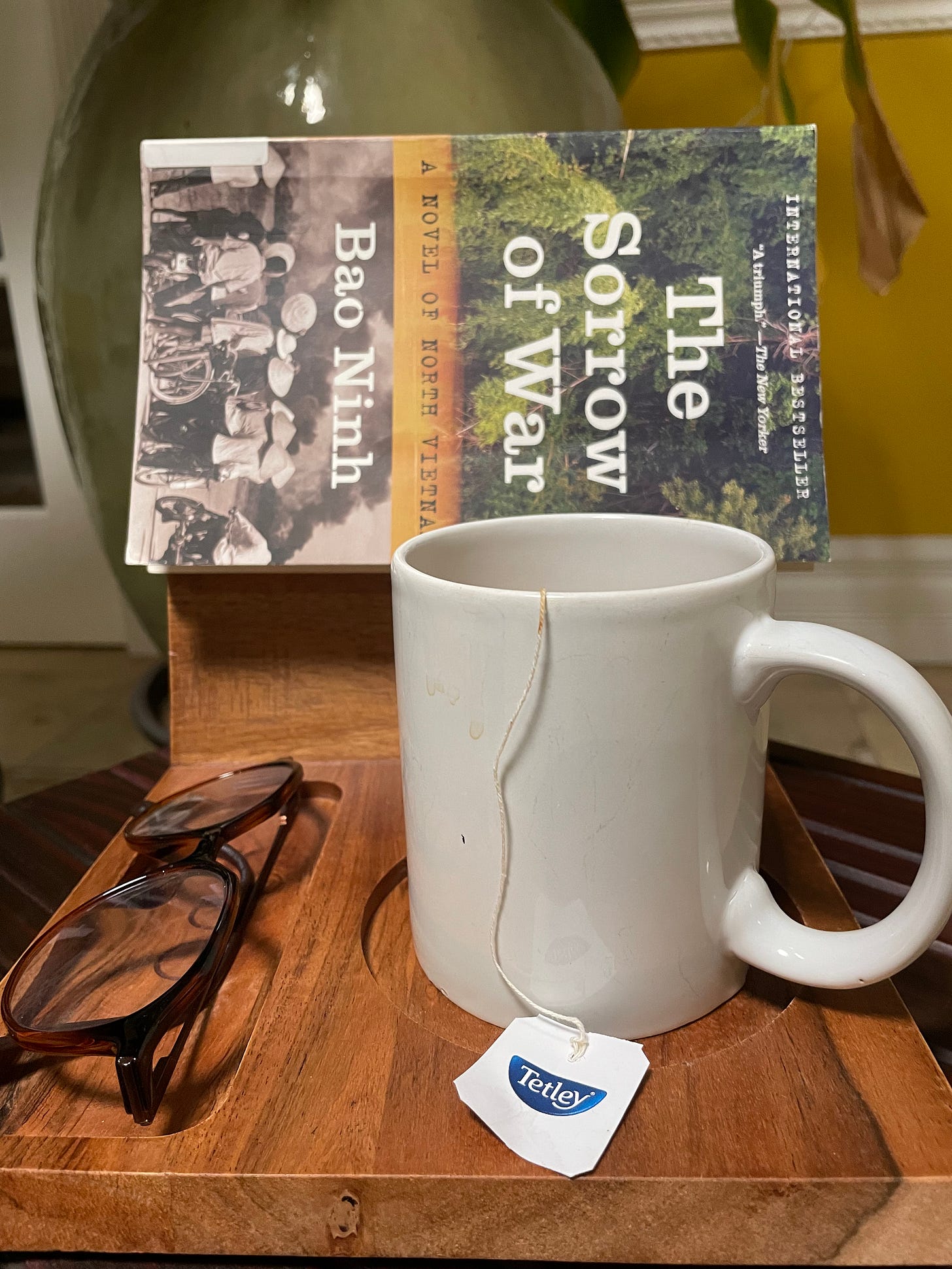

This Vietnamese novel was a disturbing read but such a timely pick. Fifty years after Vietnam, the blood continues to spill senselessly around the world engendering a continual sorrow of war.

I should have stopped reading this book after the first five pages, right when I encountered the scene after the rains had washed over the northern flank of the B3 battlefield. I kept reading, however, because that’s what I’ve had to do, to plug away, ever since I took on on this reading project.

There was also a selfish motive, too. I’ll be visiting Vietnam in a few weeks and I felt that reading the saga of war would prepare me for the visit to the war history museum in Ho Chi Minh City. Nothing, I realized as I bored through this lyrical work, prepares a reader for the gruesome scene of debris and sorrow born of one man’s blind hatred of another.

In the days that followed, crows and eagles darkened the sky. After the Americans withdrew, the rainy season came, flooding the jungle floor, turning the battlefield into a marsh whose surface water turned rust-colored from the blood. Bloatted human corpses, floating alongside the bodies of incinerated jungle animals, mixed with branches and trunks cut down by artillery, all drifting in a stinking marsh.When the flood receded, everything dried in the heat of the sun into thick mud and stinking rotten rotting meat. And down the bank and along the stream Kien dragged himself, bleeding from the mouth and from his body wound.

The story is told from the perspective of Kien, the only surviving soldier from the Glorious 27th Youth Brigade of the Vietcong. The Sorrow Of War was originally published against government wishes in Vietnam and soon went on to become an international bestseller. Author Bao Ninh, a former North Vietnamese soldier himself, is interviewed extensively in The Vietnam War, an 18-hour documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

The rain brought sadness, monotony, and starvation. In the whole Central Highlands, the immense endless landscape was covered with a deadly silence or isolated, sporadic gunfire. The life of the B3 infantrymen after the Paris agreement was a series of long, suffering days, followed by months of retreating and months of counterattacking, withdrawal, then counterattack. Victory after victory, withdrawal after withdrawal. The path of war seemed endless, desperate, and leading nowhere.

I’ve now read two novels—and both are written from opposing perspectives—and I think both are central to our understanding of the soldiers' experiences in the Vietnam War. I read Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried about a decade ago and was moved by the brilliant storytelling. A passage by O’Brien informed a passage in my own first book, Daddykins: A Memoir of My Father and I. Bao Ninh's The Sorrow Of War, however, leaves a more lasting impression of the horrors of those who actually fight in the war. While it is more poetic, more poignant, more evocative of the despair of it all, it also lays out the physical, emotional and mental abuse wrought by the business of war. Perhaps the fact that Ninh is from that soil makes it ever so personal, disturbing and somewhat of a heavier read, too.

Watching the documentary while simultaneously reading Ninh’s work burned up my entrails even more. Ken Burns, of course, gets to the heart of it all, portraying the senselessness of the ten year “American” war that followed all the protracted heartbreak of about hundred years of the French occupation of the region. The French conquest of Vietnam (from 1858–1885) was a series of military expeditions that pitted the Second French Empire, later the French Third Republic, against the Vietnamese empire of Đại Nam in the mid-late 19th century. Defeating the Vietnamese and their Chinese allies, the French colonized Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, with the region collectively referred to as French Indochina.

Midway through this novel, we encounter Kien’s narrow escape from the pistol of a young girl he had tried to spare while embroiled in a shoot-out at the police headquarters at Buon Me Thuot. While Oanh, his friend, thinks he’s saving her, he realizes, too late, that she is the enemy. Even as Kien realizes that his friend is dead, he takes aim at the girl and shoots her once, and another time, and eventually empties the entire magazine into her. It’s horrific evidence of how, in a mayhem, everybody may be vindicated for his own role in the mad killing.

Some said they had been fighting for thirty years, if you included the Japanese and the French. He had been fighting for ten years. War had been their whole world. So many lives, so many fates. The end of the fighting was like the deflation of an entire landscape, with fields, mountains, and rivers collapsing in on themselves.

In later years, when he heard stories of V-Day or watched the scenes of the fall of Saigon on film, with cheering, flags, flowers, triumphant soldiers, and joyful people, his heart would ache with sadness and envy. He and his friends had not felt that soaring, brilliant happiness he saw on film.

And why would they? They, who were stuck in their trenches, they who killed as they stood in alien landscapes surrounded by corpses. While reading The Sorrow Of War, we begin to understand why there is never a winner in a war. Those who manage to survive and return home are never the same again. The narrator’s memories of incidents from the war are so heartbreaking that there are sections I had to hop over simply in order to get to the end.

Some passages are so dissonant and unreal, as if the narrator has gone off the deep end and needs to time to enter into a state of normalcy. That’s the inherent power of this book, I believe, because it portrays the outer pandemonium of war while throwing us into the inner chaos of a human being caught in a never-ending war for reasons beyond his control. All the landmines, the trenches, the blood and gore are inside the man who has been told to kill, and kill mercilessly, because his own life depends on it.

This book does not do a thorough job of laying out the story of Vietnam and other surrounding regions before the “American” war began. The names of the many battles fought are mentioned with little context, and hence we’re thrown out of the work every few pages. Yet, in short bursts, this book conveys the magnitude of the destruction of a beautiful country and it leaves me stunned by how in fifty years, Vietnam has resurrected itself into a tourist destination. Would I recommend this book? Not wholeheartedly, no. This is a disturbing, ponderous read, yet I would recommend innumerable luminous and infinitely quotable passages on the exigencies of war.

As I turned to the last few pages of this story told by a narrator who, too, clearly, seems to be trying hard to not sink under the weight of his own post traumatic stress disorder, it was impossible to not consider the sordid realities of our world fifty years after the Vietnam War. Ken Burns and Bao Ninh, together, made me wonder what the world had learned from it all. The answer? Nothing at all, it seemed.

f