THE CHARM OF OLD BOMBAY

In a memoir by a theater doyenne, I discovered how a place grooms its people.

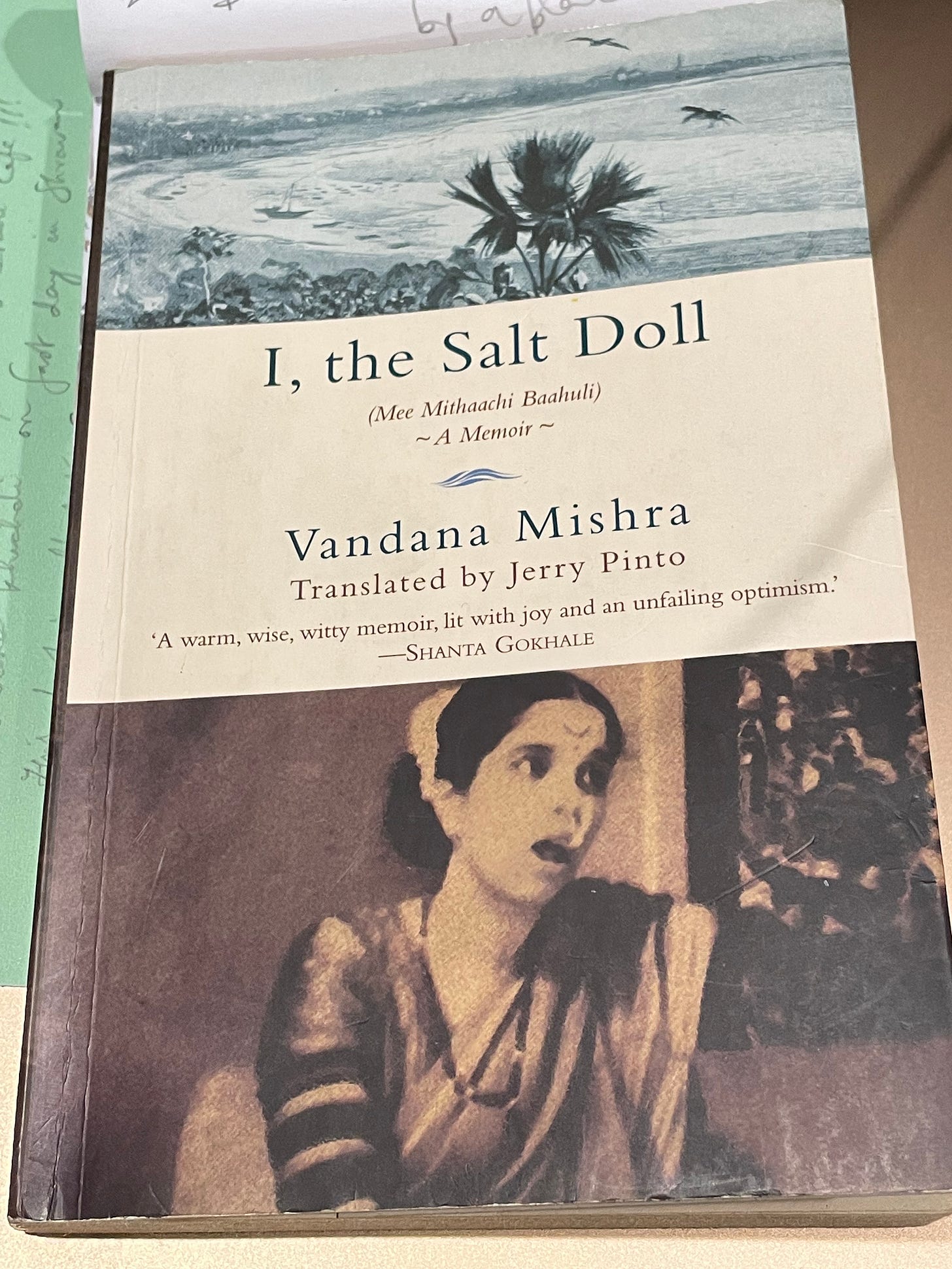

I found I, The Salt Doll, by Vandana Mishra a few years ago at a bookstore in Mumbai. Translated from the Marathi by Jerry Pinto, I, The Salt Doll (Mee Mithaachi Baahuli in Marathi) seems to sparkle with the translator’s love for Mumbai as much as the author’s own. This book is a celebration of the grit of the woman whose life it portrays and of the city called Bombay (now Mumbai).

I picked up the book at Kitab Khana, an independent bookstore that was founded in 2010 inside Mumbai’s Somaiya Bhavan, a 150-year-old building housed near the city’s harbor in what is one of the most spectacular heritage spaces in India. The Fort area of Mumbai and the stories about this part of this city informed my own book, An English Made in India.

Mumbai’s Fort district stretches from the docks in the east, to the cricket lover’s Azad Maidan in the west. In this historic heart of Mumbai rises the majestic Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Mumbai is so vast and so densely populated that it’s easy to be put off by the crowd and the chaos of the place. For me, however, every visit to this pulsating city means discovering yet another façade of a place I’d never really explored as a child while growing up in India.

Upon reading I, The Salt Doll, I realized how I’d never quite understood Bombay’s psyche even though it was the town where several of my aunts, uncles and cousins had sought to build a life. They too had moved into humble dwellings early on, into the sort of chawls that Vandana Mishra writes about. Neighbors in modest tenement buildings became part of their family, too. Mishra writes about how people’s values and personal accountability were often molded by the expectations and comportment of residents in such a place. She writes about how she was groomed by the community in the neighborhood of Girgaon.

“Girgaon had given me my culture. It had taught me valuable lessons in living. That one should help one another; that one should live in harmony with everyone; that the search for knowledge was important and learning was important; that humanism should be nurtured at all costs.”

The sense of community is so strong in a metropolis like Mumbai that it seeps into one’s veins. I’ve noticed that people from Bombay have a distinct perspective on life. People often say they can spot an ex-Mumbaikar (a “Mumbaikar” is a resident of Mumbai) from a mile away. Mumbaikers adapt easily. They’re a lot more “with-it” and resourceful. They’re curious about others and more involved in other people’s lives. They’re certainly more thoughtful and helpful. Needless to say, that may often mean they’re a tad meddlesome. Vandana Mishra addresses this aspect of life in a Bombay chawl with her characteristic dry humor: “The modern notion of privacy had not spread very far in society. People tried to live together and also tried to keep from interfering in each other’s lives.”

I, The Salt Doll, is the story of a woman called Sushila Lotlikar who was born in 1927. When Sushila’s father dies unexpectedly early, her mother, Lakshmibai, a homemaker, has only one option: to go to her late husband’s village and pursue a life working in the large plantation home of her husband’s uncle. However, when he tells her that she and her children may stay in his home, he also makes it clear that she must shave her head to assume the mantle of widowhood. Lakshmibai refuses.

Instead, she returns to the city of Bombay with her three children and begins to live in a chawl and begins her hunt for a job. Following a suggestion from a well-wisher, she enrolls into nursing school, thus beginning a typical life of a Mumbaikar, one of hard work, economy and efficiency.

Just as the author’s family makes ends meet on a nurse’s salary, fate intervenes. An accident renders Lakshmibai unfit for work. Sushila is forced to abandon her dreams of an education in medicine. Instead, as a fourteen-year-old, she’s recruited by Dada Altekar of the Little Theatre Group for training as an actor. Sushila is bright and talented and she goes on to make a name for herself—with the stage name of Vandana Mishra—in Marathi as well as Gujarati and Marwari theater. I, The Salt Doll, is hence also a tale about the grit and determination of a woman in a city that helps her achieve her aspirations for a dignified life despite her penurious beginnings.

I, The Salt Doll, first caught my attention with its unusual title and cover. The salt doll story is a parable in every culture about the fleeting nature of our lives against the vastness of time. Each of us is simply like the salt doll that frolics on the shore and tests the waters of the ocean in order to understand its depth. As the doll wades deeper into the sea, it melts a little more until, one day, it becomes one with the waters. Each of us is put on the shore and will one day return to the vast beyond. Just as the title suggests, this is a narrative about life on the shore and how we must live it.

Mishra’s work drips with nostalgia and this book must be on every Mumbai-lover’s list. I, The Salt Doll does not romanticize Bombay. What it does do, however, is show us its vivacious, warm and welcoming side. Vandana Mishra does a superlative job of describing the colors, sounds and smells of the town in pre and post independence India. We hear “Cooo-cooo-coo”, the "rooster-like call" of the Muslim bread vendor who brings bread or “pao”, still so warm from the oven. By the time August rolls around and it’s time for Lord Ganesha’s birthday, people practice “baalye”, in which dancers form circles and clap to a specific rhythm. There’s always water shortage in the crowded city and we learn how policemen amble around the chawls speaking into blow-horns to warn residents.

“Films were also advertised in the same way on a hand cart. Posters would be affixed on both the sides of a hand cart and in a shrill voice, the announcement, “Don’t forget, from tomorrow, at the Roxy, Ashok Kumar in Kismet.”

While the book is filled with delightful, unexpected details of quotidian life from the Bombay of ‘30s and ‘40s, I was struck by the medley of songs from many decades of Hindi cinema. I hummed along as I encountered anecdotes about my favorites. I spotted Lata Mangeshkar’s Aye Mere Watan Ke Logo. There was Pankaj Mullick’s Chale Pawan Ki Chaal Jag Mein that my late father hummed so often. Mishra writes a profound paragraph about what the Kishore Kumar hit Zindagi ke safar mein, from the Hindi movie Aap Ki Kasam, meant to her.

We all seem to be on a journey. Stations would pass and fall behind and we would all move on. Our job was to think about the future, not to look back constantly. I loved the song from Aap Ki Kasam: “Zindagi ke safar mein guzar jaate hai jo makaam, woh phir nahin aate.” (In the journey of life, the stages we pass will never return.) This is truly what life is about. But it is also true that sometimes the stations that we think we have passed suddenly return in different forms. This is what happened to me. I thought I had left the stations marked ‘Theatre’ in 1947 but after twenty-two years, I found myself at the same platform again.

Through Mishra’s words, we experience the changes in her life. When she compares the Bombay of then with the Mumbai of now, it’s hard not to wonder about the effect of place on people—and vice versa. No matter what, this megapolis of 20 million people has remained a melting pot and a haven for many.

I never tired of her descriptions of people and their attire. At one end of their chawl is a narrow alleyway that leads to Khotachiwadi housing Christians from Goa. Behind the chawl is where a community of Parsis live, spread out as they are across “baugs” or enclaves at Colaba or Babulnath.

“The Parsis were rich and enterprising. They loved cars and drove around in Buicks, Morrises and Baby Austins. Their wives wore georgette saris and blouses without sleeves. Their plump fair children always caught the eye.”

Despite my fascination with I, The Salt Doll, it’s not a book I would opt to read for its lyricism. The narrative is bone-dry and the tone is direct. Jerry Pinto is Mishra’s faithful conduit at rendering her voice on the page. In some arduous passages, she tends to plunge into what are insanely long lists of people and events. Indeed Vandana Mishra could have been my 93-year old aunt Vijaya, sitting by my side and narrating the tangled story of her life and times, while I listened to her out of sheer love hoping secretly for a bathroom break.

For a long time, I’ve been a fan of Mumbai’s Jerry Pinto, a sensitive writer with an impressive list of publications, translations and awards. He has often talked about the value of an infinite number of revisions and the number of overhauls that ultimately led to the publication of one of his own heartbreaking novels, Em and The Big Hoom.

I believe that reading a good piece of writing is similar to experiencing the lucidity of water in the open seas. This clarity is measured by how far down light can penetrate through the water column. In Pinto’s craft, I most certainly can look down and see the rocks and starfish below.

Such a charming read! I loved the metaphor of the salt doll; we flavor life with our presence, and death too, even as we dissolve into nothingness. Anything with Jerry Pinto's stamp on it has to be great in my book. Looking forward to your next post :)

I am a Mumbaikar and loved reading Kalpana’s writing. Photos really embellish the story.