THE BOOK SET IN BANGALORE

Another of Vivek Shanbhag's novels hit the stands ten weeks ago and I had to make a beeline for it during my short stay in Bangalore. The international accolades run for pages.

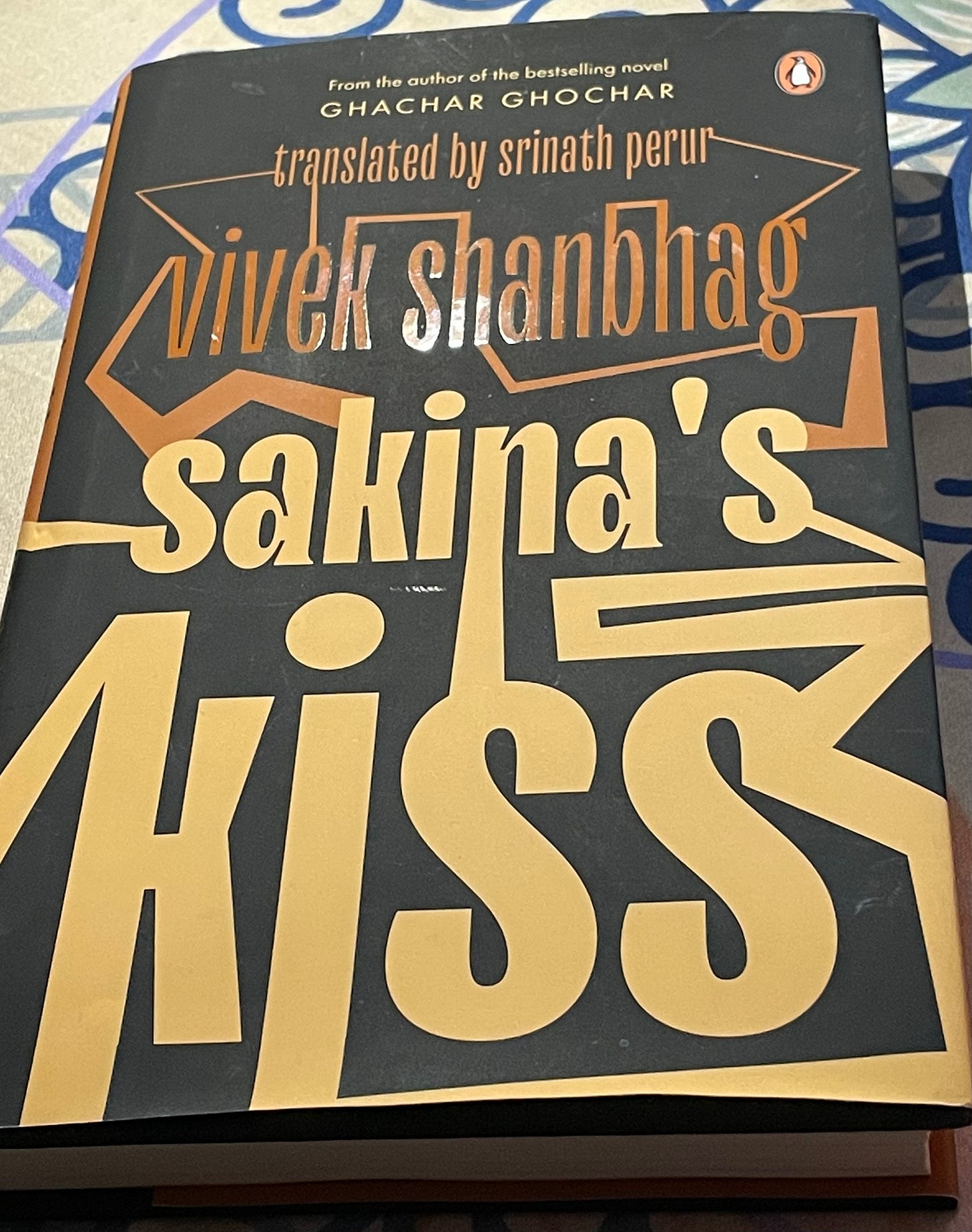

I found an autographed copy of Vivek Shanbhag’s Sakina’s Kiss at Blossom Book House on Church Street in Bangalore. How do I convey to my western readers how exciting the book scene is in Bangalore and Delhi? You may never find the books you want in the small, often uncategorized and chaotic book havens in these sprawling Indian cities but you’ll always discover something you’d never thought you’d find. Blossom has over 200, 000 books in stock and if just one of its stores made me go berserk, imagine my consternation at discovering two other branches in close proximity.

For several months, I’d been eager to get my hands on Sakina’s Kiss. When I turned the pages, I discovered that the reviews of Shanbhag’s prose in translation from the Kannada language filled three pages. They set the stage for what was about to take over my life for two days.

This compelling book places us inside a middle-class apartment in India’s Bangalore. We drop into the head of Venkat, an engineer hailing from the village, who has managed to climb the ladder of success in information technology in the city of Bangalore. Venkat is forever preoccupied with the idea of self-improvement and with visibly wearing the markers of success in a globalizing India.

We believe our friends and relatives see us as successful. But no one spells out what exactly that means. They don’t need to. It’s common knowledge that the answers to a few simple questions give the measure of worldly progress. A house of one’s own? If so, which area, who is the builder, how many BHK? Make of car? Kids? If so, which school? For people like us, who have successfully passed those milestones, there comes the test of being evaluated by the conduct and achievements of our children. That is where we stand now.

Set over four mostly sleepless days, the opening is jarring. One evening Venkat answers urgent knocks on the door to his apartment to find two classmates from high school claiming they need to speak with his daughter Rekha. Over the next few days his humdrum life is overturned by strange events, and strangers who are beneath his station in life. Venkat is forced to entertain goondas and ne’er-do-wells with whom he would never want to be seen.

We learn early on that at the time of his marriage, Venkat challenged his wife Viji, telling her that there should be no secrets at all between a man and his wife. Venkat, it turns out, is not that different from the Hindu demon Ravana. He seems to possess ten heads; each head, packed with truckloads of biases, insecurities and secrets, does not know what the other is thinking. By and by, the two women in his life are on to him.

You’re only concerned because your daughter is involved. You would have no problem if it were some other woman they were doing it to. I don’t know who you are sometimes. It’s like there’s another man inside you, waiting to get out.

We learn that his daughter Rekha, once such a sweet and happy child, has become more intransigent with every passing year. As we encounter the shadiness of the men who come to confront Venkat about his daughter, the narrator also unravels a parallel narrative through which we learn of a betrayal and disappearance from long ago. By and by, Venkat’s dastardliness projects out of the pages, shocking us time and time again, and making Venkat seem more unreliable, despicable and villainous.

Venkat is like the silk worm that feeds on mulberry leaves, eats many times its own weight and bloats to several times its size. Our protagonist feeds on self-help books; gorges on them, feeding his face so much that all the “self-improvement” he engages in make him into someone he does not even recognize anymore. He spins himself a cocoon through which light won’t penetrate and when his daughter’s life is in danger, he is in boiling water, after all.

This is a riveting novel. I’m addicted to Shanbhag’s surefooted storytelling. His artful dialogue is some of the most effective and effortless I’ve seen in contemporary fiction from India. When we read his stories, we’re in there with the characters, swimming in all the ugliness, hating it all, yet unable to turn our gaze to anything else. I read this book in two sittings only because I was traveling. I read his previous novel Ghachar Ghochar in one sitting over three hours.

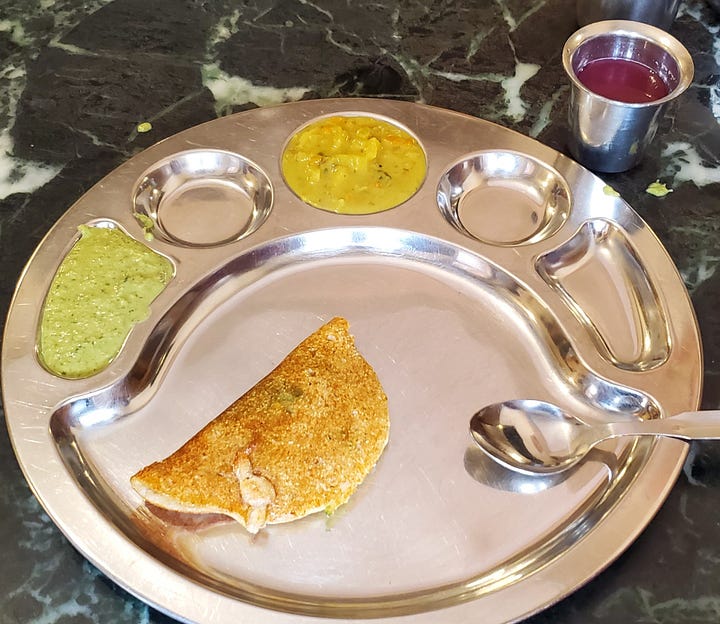

That having been said, I found this novel a little elusive, and the ending left me a tad dissatisfied. Judging by the many stellar reviews for Sakina’s Kiss, however, it seems as if this discomfiture may well be my problem. The feeling I had was the same as that on the afternoon I went to Bangalore’s MTR for lunch. The South Indian menu was inviting on paper but on the plate it did not add up to a perfect lunch. At least three dishes were not up to the mark and I expected MTR to deliver on every count.

On a similar vein, by the time I turned to the last page of the novel and the story barreled to its end, it was clear that the event of Rekha’s disappearance was not exactly the focus of the novel. Instead, the story lay in the psychological unmooring of our protagonist. Brilliant as the novel was, given its suspenseful setup at the outset, it felt like a bit of a letdown as I grappled with the denouement and its murky close. Yet, as I thought about the work more and went back to reread sections of the book, its wily brilliance showed itself some more. Venkat, our suave techie, was as much of a goonda as the thugs who stopped by his home.

Shanbhag takes us on this fantastic ride into the dysfunctionality of a small family of three in which the father’s biases and hypocrisies engender a monster of a child and a rebel of a wife. But what to make of the father himself? Towards the end of the novel, the narrator’s voice echoes through the pages in what I thought was a penetrating reflection upon the whole narrative.

I’m looking for some sign of disarray, some sort of stain. Something has happened here, but I don’t know what. A sharp knife has been thrust in and removed so quickly that there is no trace of blood anywhere. I’m waiting for the blood to spurt out and show me the wound.