THE BEAUTY IN BREVITY

Last week's novel hardly made a dent on me but this week's collection of essays is now pockmarked and dog-eared, ruined almost, by the pencil gashes rising from my own writing dreams.

“I’ve forgotten the precise hour of the exact day I decided to start writing, but that hour exists, and that day exists; that decision, the decision to start writing, is one I made abruptly, on a Paris bus, between place de la Republique and place de la Bastille.”

~~~ Jean-Philippe Toussaint, The Day I Began To Write

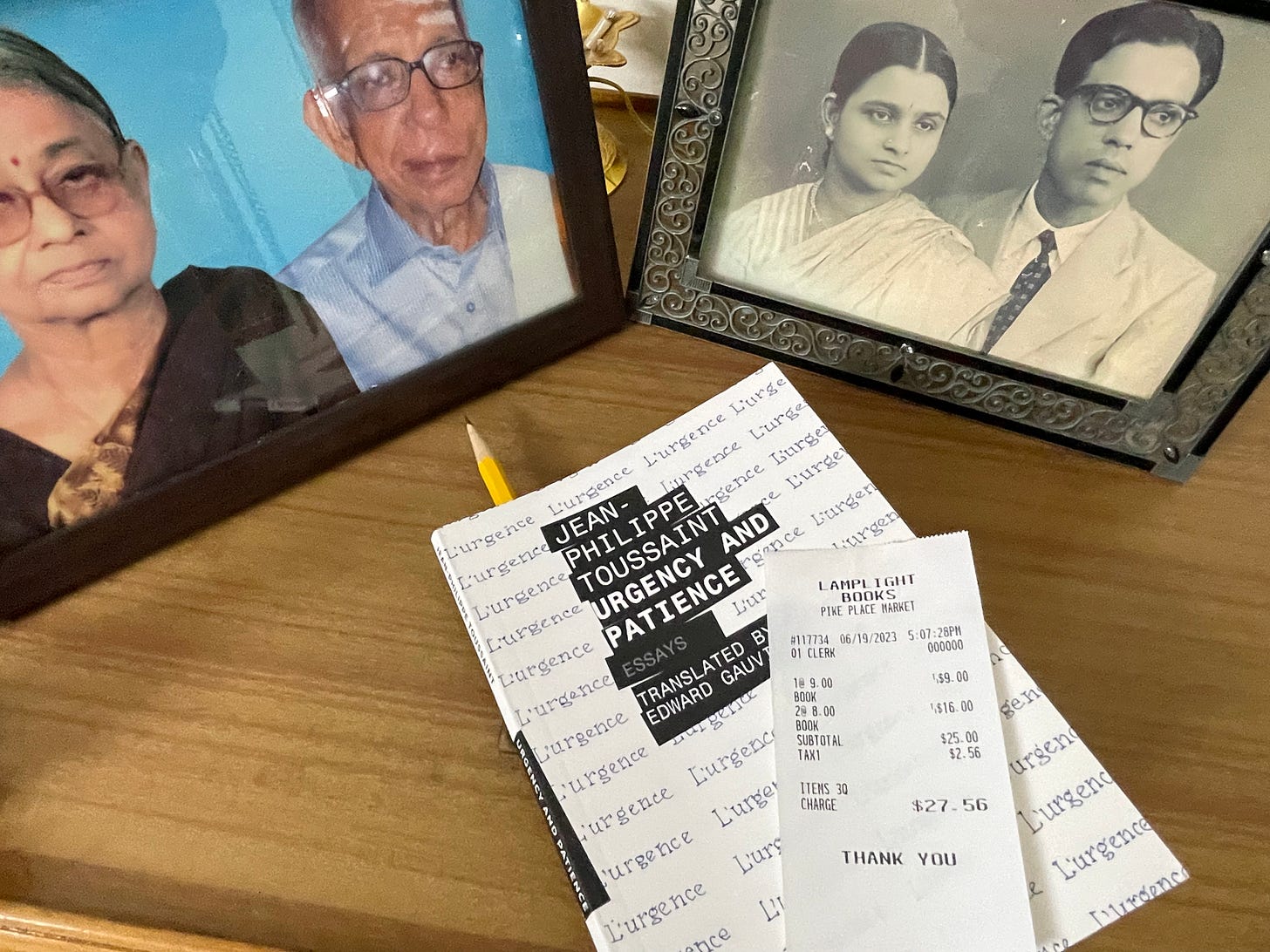

On a trip to Seattle in June, I happened upon a tiny book called Urgency and Patience at a used books haven called Lamplight Books, a terrific bookstore specializing in vintage, classic, and out-of-print books in Seattle’s historic Pike Place Market.

It’s never clear how some books enter my life at a critical moment in my writing journey. Consider, for a moment, how this tiny 58-paged collection of essays contrasts with my pick of the last two weeks. No emoji may express the frustration of the previous week of reading, one that preceded an exhausting 24-hour journey on Qatar Airways from San Francisco to India’s Chennai.

This week, I’m ecstatic to report a life-changing reading experience that reminded me of a key moment in my own writing journey. Mine began in Paris, too, in a tiny room on the first floor of an apartment on Avenue Charles Floquet in August 1998 when I grappled with the truth that work, when it’s one’s calling, never feels like work. I realized that work ought to be a response from my entire being and the only way I’d know to be.

Every writer, every practitioner of art, should keep this little instruction manual called Jean-Philippe Toussaint’s Urgency and Patience by their bedside to read and reread on days when they feel adrift amid the scaffoldings of their life’s work. Toussaint’s books have been translated into more than twenty languages and he is a prominent European photographer, filmmaker and writer. It’s clear how his different gifts flow together into a confluence of preternatural sentences that I think everyone must read at least once in their lives. Toussaint is the author of nine novels, and the winner of myriad literary prizes, including the Prix Decembre for The Truth about Marie. The translator of Toussaint’s work, Edward Gauvin, is no bromide either. The translator of eight works of prose fiction and (over 300!) graphic novels and a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, Edward Gauvin was a 2007 fellow at the American Literary Translators Association conference.

I know nothing about how Toussaint and Gauvin worked together but Urgency And Patience has the quality of a waltz between two writers whose footwork is as delightful as the workings of their minds. Toussaint illustrates how two qualities, urgency and patience, inform the vision of a writing project. I use the work “writing project” but this work may be applicable to every dream of a life’s work. With great clarity, Toussaint tells us what paves the way for transcendent work.

There are always, I believe, two seemingly irreconcilable notions at play in writing: urgency and patience.

Urgency, which calls on impulse, ardor, speed—and patience, which requires slowness, steadfastness, and effort. And yet both are indispensable to writing a book in varying proportions, distinct doses, every writer working out an individual alchemy, one or the other of these traits being dominant and the other recessive, like alleles that decide the color of one’s eyes. And so, among writers, there are the urgent and the patient, those in whom urgency dominates (Rimbaud, Faulkner, Dostoyevsky) and those in whom patience prevails—Flaubert, of course, patience itself.

Every essay is packed with with many quotable passages on the writing process. My copy of this book is now full of pencil marks of underlined sentences and entire pages. I haven’t yet read Dostoyevsky’s Crime And Punishment but after reading this book, I realize I must read it in order to grasp the value of the essay that reveals the impact of this work on the author.

Toussaint claims to have read very little even into his 21st year of life and was urged to read Crime And Punishment by his sister. Reading the book launched his writing career. Now I feel I need to discover what he found in the work that shaped his reading habit and filled him with both a sense of wonderment and purpose. I quote a few sentences from the essay with which Toussaint manages to, once again, drag us, kicking and screaming, into the circle of his thoughts.

But stranger yet is that “the thing”—the crime, the crime so hard for the character to name—seems unspeakable even for the author himself. Dostoevsky persists in circling it, always avoiding it, evading it, dodging it, while constantly implying it, consciously putting it front and center in the book’s every action, no matter how slight. The crime in Crime And Punishment is a sphere whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere.

This essay ends as memorably as all in this collection, teaching us how a sentence that is as local and as universal as, say, a stop sign or a walk sign anywhere in the world, must propel every reader or creator forward to reach his own truth. Toussaint claims to have taken Dostoyevsky’s significant work, “right to the jaw.”

“A book must be an ax for the frozen sea within,” said Kafka. An ax? In Crime And Punishment, I saw the bright blade of that ax—literature—gleaming for the first time.

In the closing essays—one titled “For Samuel Beckett “ and another “In Bus 63“—Toussaint drills down into what writing must attempt to do and he conveys the power of one man’s words on his own psyche and his work. That author is a gentleman called Samuel Beckett.

Beyond language, what remains in a book when one has made abstractions of the characters and story? The author remains, a solitude remains, a voice at once human and neglected. Beckett’s work is fundamentally human; it expresses something of the wellspring of human truth at its purest. There are many writers we can admire but very few we can, beyond literary admiration, simply love.

I don’t wish to say anything more but the next two pages of this work I have read several times. Each time it reveals itself in different ways to me. Again and again, we travel with Toussaint to where exactly he was, physically, when he read a work that moved him so much that he would recall where else he had been the next time that he read it.

We turn to the last page, page number 58, and we’re with Toussaint right about the time he descends from bus number 63—a bus I remember taking every other day in Paris when I lived there although I must admit I didn’t once fall down flat on the sidewalk—in awe of having seen the light right about when he’s at the intersection of Boulevard Saint-Germain and rue Saint-Jacques. Toussaint had just turned to the last page of a work called Malone Dies by Samuel Beckett.