THAT MIDAS TOUCH IN CALIFORNIA

A new exhibit on the California Gold Rush at Los Altos History Museum opened my eyes to the tumultuous times. Little has changed in the desires—and the attitudes—of people.

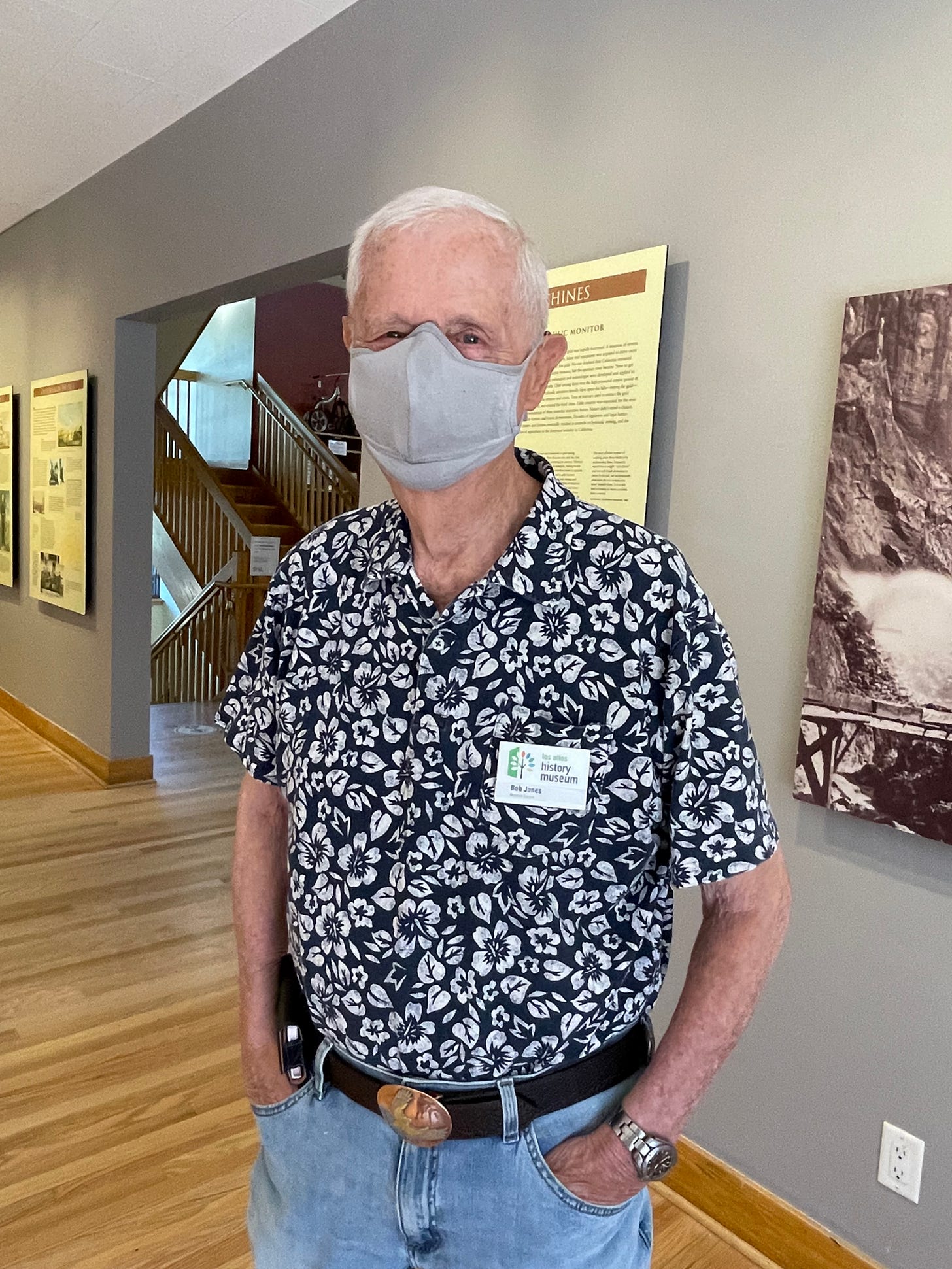

Bob Jones dropped his gold coin into my palm. The coin was etched with letters and numbers and I wondered, for a brief second, what those markings signified. “I had a gold mine in the seventies, you know,” Bob said. My fingers traced the edges of the sleek, elegant coin. It was one troy ounce in weight and surprisingly heavy against my hand.

A troy ounce is 2.75 grams more than a regular ounce which translates to 28.35 grams. There I was, holding in my palm over 31.1 grams of 24-karat gold—worth over $1810 in value—and I had already begun to feel like the fictitious Sam MacKenna as he bolted down the mountains, gold nuggets in his satchel. I sensed a momentary tug of vanity tinged with greed. The love for gold never gets old. Soon enough, however, the luster of the metal dimmed and I duly passed the coin back to the sprightly 87-year-old in front of me.

The day I met Bob, he was bustling about, albeit cautiously, at the Los Altos History Museum, guiding people as they walked in on the first day of the exhibit called “Gold Fever”. Bob’s own gold mine had been in Butte county and he sold it a long time ago. He told me how from 1903 to 1958, the mines at Butte County were busy. The county produced 103,800 ounces of gold from lode mines and 2,332,960 ounces from placer mines. While there is no record of gold production at Butte County before1880, he believes there would have been intense activity.

Bob Jones’ day job in Santa Clara valley of the sixties had been at LMSC, Lockheed Missiles and Space Company. This unit of the Lockheed Corporation was once located in the city of Sunnyvale (adjacent to Moffett Field) where it operated a satellite development and manufacturing plant. Bob had been an engineer and his expertise had been in missiles, a line of work that demanded precision. Fascinating as that was, I was more intrigued by the story of his gold mine. I also discovered that I had a personal connection to the name of the mine he bought. “Do you know the tale about King Midas?” he asked.

King Midas and the Golden Touch was one of the first stories my father told me when I was a child and I heard it repeated to all the children who visited us. Sometimes, while telling his tale about King Midas my father became an actor, too, playacting the moment when King Midas’ daughter became inert as a lifeless gold statue as soon as her father touched her. My late father’s zest for life revisited me that afternoon in Los Altos while my husband and I listened to Bob.

After we chatted about the mine, Bob asked us if we had heard about the concept of placer mining in which different techniques were used to sift out valuable metals from sediments in river channels, beach sands, or other environments. In North America, placer mining was the method of mining used during several Gold Rushes, particularly during the California Gold Rush. “Placer” is a Spanish word describing an alluvial or glacial deposit of sand or gravel. Even as Bob began to talk about it, I realized that it was probably how the town called Placerville got its name. We had driven past the town many times en route to Lake Tahoe on US highway 50—this highway is now officially called “El Dorado” which describes, in Spanish yet again, a place of fabulous riches. I could not believe the innumerable references, right where I lived, to the days of this lust for gold even though the peak of this fever lasted just about seven years.

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) began in the town of Columa on January 24, 1848, when gold was discovered by one James W. Marshall who had been overseeing the sawmill’s construction on the American River at Sutter's Mill. The story about the discovery of gold in Coloma, in new age parlance, went viral. The news of this discovery brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the United States and abroad. The sudden influx of gold into the money supply gave a fillip to the American economy. California’s fortunes changed forever as it proceeded rapidly to statehood.

The term “49ers” is a reference to the frenzied hunt for gold in the year 1849 in Northern California. The California Gold Rush rocked the fortunes of many families. Many returned home after losing all their life savings. Still others, lured by the possibilities of profiting from the new settlements growing around the Gold Rush, arrived in California in droves during those years in order to start new ventures. By 1849, these “49ers”, in other words, thousands of gold-diggers—or prospectors—descended upon the site of Sutter’s Mill, and the surrounding region, hoping to strike it rich. To get a sense of what a sizable nugget of gold looks like, don’t miss a video of this handsome piece of gold discovered in Butte county in 2014.

When I wanted to read up a little about the Gold Rush, a google search of the term “49ers”, proved worthless. It pulled up pages and pages of reference to the revered American football team, the San Francisco 49ers. It was also a revelatory moment about how quickly, especially in this new age, history loses ground.

While learning about old Placerville’s connection to gold fever, I came to know of its other name, “Hangtown”. Bob Jones pointed out that the city earned its macabre nickname in 1849 after three men accused of robbery and attempted murder were sentenced to death by hanging. Apparently, these men spoke no English at all and were not present at the trial where the death sentence was handed down. Justice in these mining camps was often meted out in an extralegal manner in the years of the Gold Rush.

I was reflecting on how utterly believable all this was in light of recent events in the United States. At Placerville today, a dummy named George still hangs from a historical spot and the tree used for hanging still exists as a stump. While the city voted unanimously to slash the noose from the town’s logo following a wave of social justice protests after the police killing of George Floyd, they decided to leave the other name as it was.

I have come to believe that old lessons from history will never endure unless there is a concerted effort to teach future generations about the past. In some sense, I’m ambivalent about this nation’s decision to remove symbols of hatred and violence. How will we teach future generations about all the horrific things that happened in the past if we remove the relics from the period? Instead, I feel we must hold on to them, perhaps in a different way, to recall the egregiousness of the past, denounce the acts categorically and establish that such things can never happen in the future.

At the Los Altos History Museum, the thoughtful curation of the information on the Gold Rush spelt out many of the inequities of the past. For me, it was eye-opening in many ways. If you’re a recent immigrant—I landed in San Jose as the spouse of a high tech professional in 1985—there is a tendency to assume that the diversity of California, especially that of Silicon Valley, is a thing merely of the last few decades sparked by high tech wealth. I did not realize how much California’s Gold Rush contributed to the multi-ethnic population of the state itself. The city of San Francisco grew dramatically in the years of the Gold Rush. Its population in January 1848 was 800. It was 50,000 just five years later. It also became the most culturally and ethnically diverse city in the world at that time.

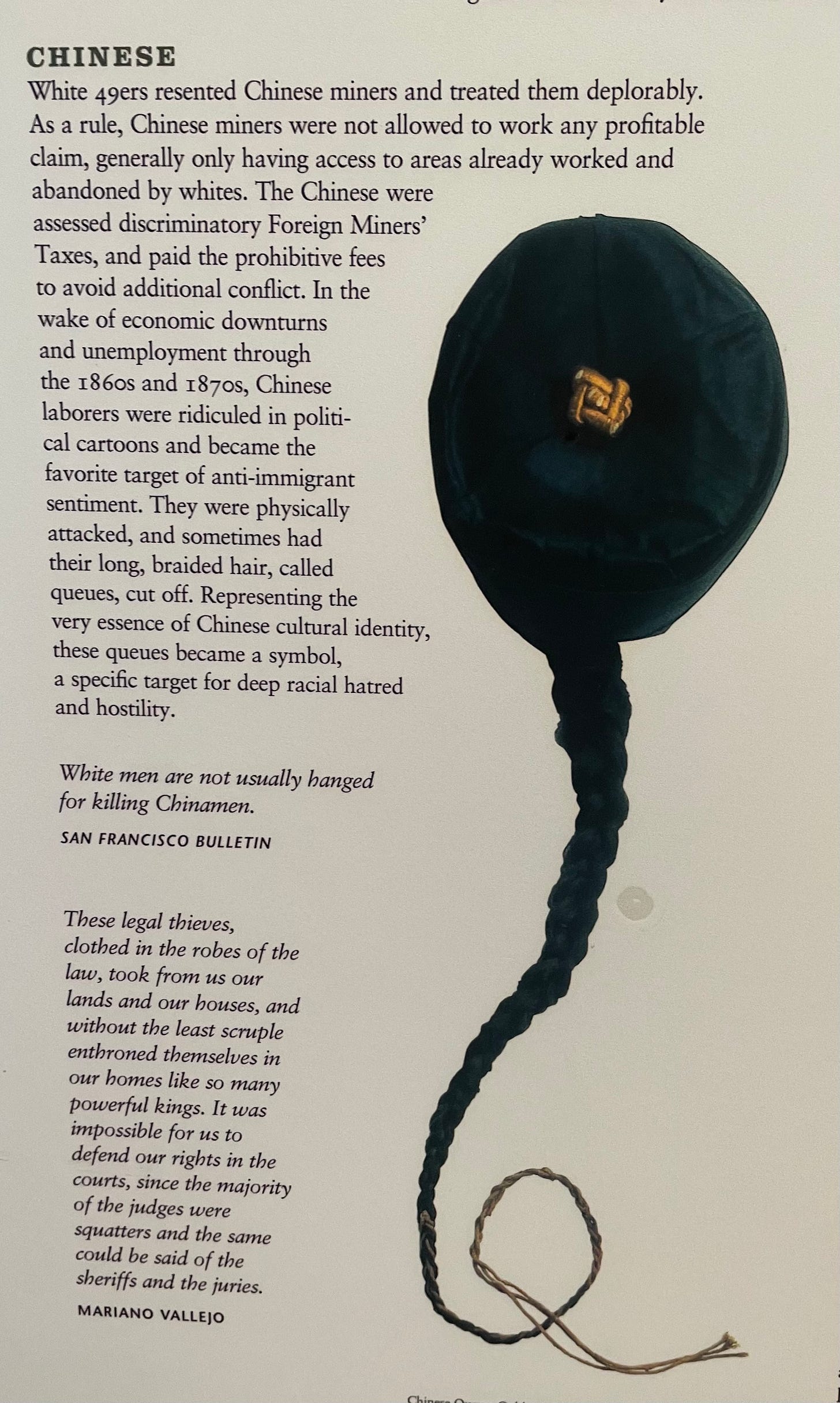

The years around the Gold Rush were also followed by the discovery of silver. Together, both gold and silver brought unbelievable amounts of wealth to many people and to the state of California. But they also ushered untold misery and hardship in the lives of many. 25, 000 people of Chinese ancestry poured into California in search of Gum Shan or the gold mountain. The treatment meted out to people who were not white-skinned, to people who did not speak English, to people who just looked “different”, was harsh. Most Chinese were only allowed to work as low-paid laborers. They often sweated it out at sites that were not lucrative in the eyes of white miners and were often subject discriminatory taxes and violence. The first foreign miners’ license tax in 1850 was yet another way to dissuade foreigners from seeking their share of the fortune. Anyone who was not American, especially if they were identifiable as “other”, was expected to pay a prohibitive tax and by 1870, this foreign miners’ tax was bringing in nearly one quarter of California’s revenue. Of course, the Gold Rush altered the lives of native Californians, too, accelerating the Native American population's decline from disease, starvation and massacre. The indigenous population of California plummeted from 150,000 in 1848 to 30,000 in 1870, according to the 1925 book Handbook of the Indians of California. In 1900, their population dwindled to 16,000. When I processed all that had happened in those years, the story about the hangings that took place at Placerville was hardly shocking.

Later that afternoon, after we had left the museum and merged into the highway back home, I was struck by some of the other things that Bob Jones had said. He’d wondered why some old means of transport were forever erased from Bay Area life. Trams as well as the railroads that once connected all the small towns of the Bay Area had ultimately dissolved into roads. “Why did they have to go?” Bob had wondered aloud.

When I wrote a post two weeks ago on the transformation of my hometown of Saratoga, I too had asked the same question about the extinct railway corridor. The same rails that transported apricots and prunes could have progressively evolved for humans, too. Given that land was in plenty around these parts, we could have had several different public options open to us, along with the private. Even though we now had the Caltrain and the BART system, none of these was extensive or fast enough for a congested Bay Area with a population of eight million people.

I thought that someone like Bob might have loved to hop into public transport, especially as he aged. To my astonishment, he confessed that he actually preferred to drive and that he never ever tired of getting behind the wheel.

“I was once a race car driver,” he said. He was masked but I didn’t miss the light in his eyes as he talked about all four of his cars. Among them is a Porsche and a Maserati. As I stood in that museum, I realized that I may have struck gold, after all. I would have to mine Bob Jones for so many other stories.

Love this!!! Thank you for the comment.

Bob Jones in this story of king Midas was in fact my uncle and he truly has some amazing stories of adventures and career choices through out his life. He loves motorcycles both in racing and driving them his passion for fame has done him well. He once owned a 1969 porche that he raced several times even against the movie star Steve McQueen . Albeit Steve was much more experienced and my uncle always gave it his best. After a few years he had sold that porche and from there sometime the comedian Jerry Sienfield had bought that porche which is valued at about 3 million dollars now. If you ever watch Sienfields shows that porche is a poster on the wall in few of there shots. I have always admired my uncle and feel I to have the same life as he by having the love to be behind a race of some sort. We may have same life to this day when I visit my uncle I am always in awe from pictures on his walk in his home with other stars he has met even jay Leno is on his wall. My grandfather too was a very popular man and had done some amazing things with his love for horses and just like my uncle he to have met some movie stars like John Wayne.

I’m very proud of both of them and often wondered why my father oand morther sheltered me from exploring that life style I feel I follow there footsteps more than my own father. I love telling all the stories of them both and there popularity with the famous people.