TALKING ABOUT MY HUSBAND

Upon reading a Macedonian collection of stories—titled "My Husband"—I declare that my husband emerges fragrant as the Heritage English rose.

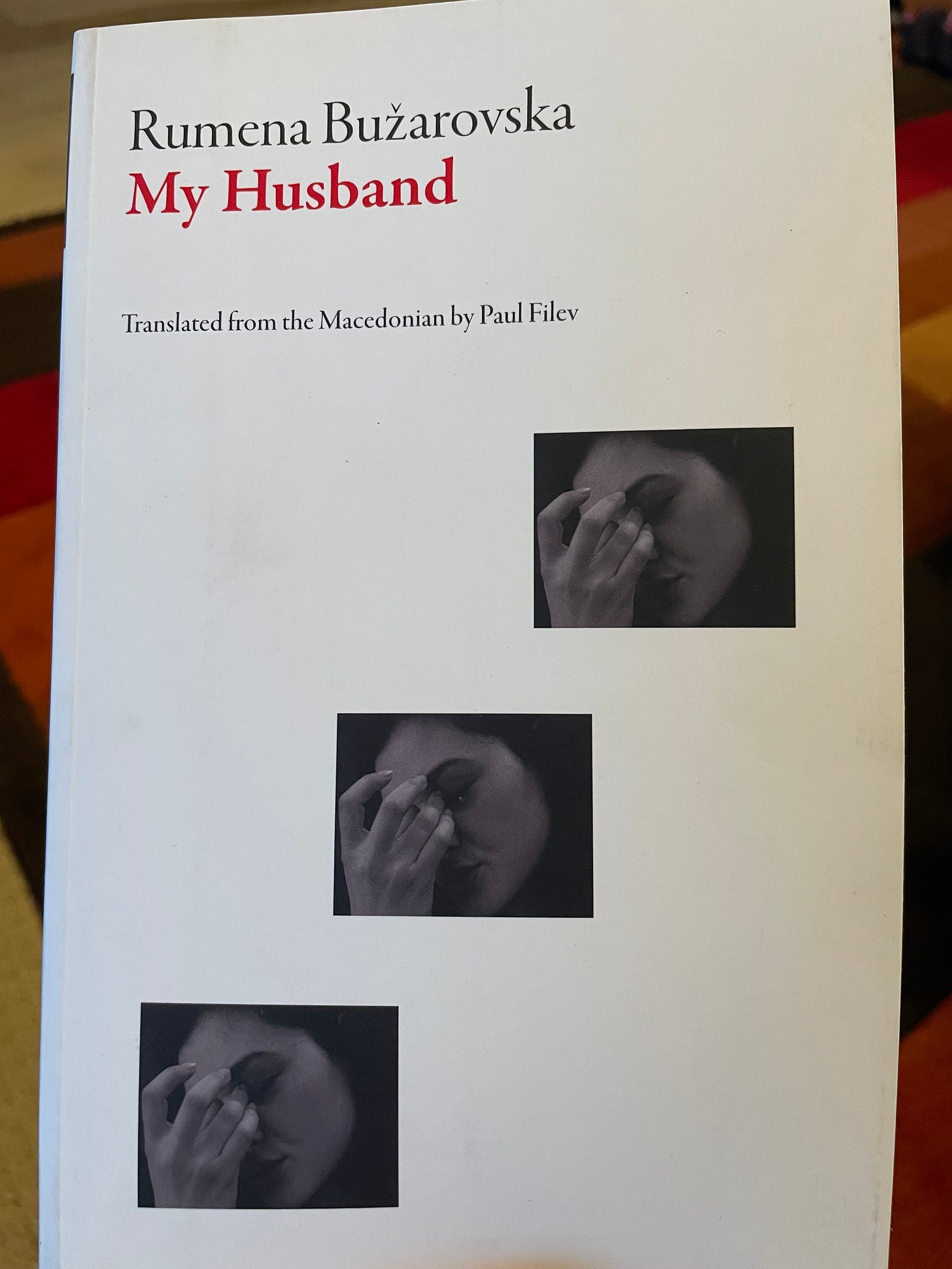

Many moons ago, when I picked up this story collection from an obscure shelf at Kepler’s Books in Menlo Park, I’d not heard of the young Macedonian author who had penned many searing portraits of husbands. MY HUSBAND, translated by Paul Filev, is vibrant, urgent and provocative. I’m thrilled to have alighted upon the work of Rumena Bužarovska by chance on a casual visit to my favorite bookstore. I’m almost certain that anyone who reads her very first sentence will invariably end up reading her very last.

With the exception, perhaps, of one man, most of the husbands in Bužarovska’s book suck—unforgivably, unabashedly, unmitigatedly. They never see beyond the end of their noses. The boorishness of these men—and the timorousness of their women who are unable to stanch their gaslighting and abuse—makes the book topical in a post #MeToo world. After reading Bužarovska’s work, however, I’m also certain that I may need to build a Taj Mahal to my partner of almost forty years. I’ve been told—by my children, their father and my own parents—that, like him, I too am not that easy to live with, just in case I’d assumed otherwise.

Clearly no one is easy to live with. Humans are peculiar. We are wedded to habit and often blissfully unaware of what irks others about us. Even when two people fall in love, their cocoon of love unravels as pet peeves, patterns of behavior and insecurities saw through the early bond. Years later, a trivial mannerism in a partner (who once seemed so endearing) becomes a significant source of irritation to the other partner.

Unfortunately, the men in this collection aren’t just mildly irritating. They are adulterers, cheats and hypocrites. There’s the gynecologist who caresses a woman as part of his procedure. There’s the husband who’s endlessly vain about his (bad) poetry. They are mostly just terrible guys and it’s inevitable that their marriages begin to implode a few years in.

MY HUSBAND lets us hover over precisely those moments of disgruntlement in a marriage. The narratives feel like the mature work of a woman who has spent years watching many men in a panoply of marriages. Bužarovska has a sharp eye. She wields an eviscerating pen, too, one that is intrepid in jumping headlong into the dark abyss of relationships where resentments, suspicions, petty jealousies and anxieties fester and bubble.

Midway through the book, I began reading about the author herself. I was surprised to discover that Rumena Bužarovska was relatively young in the literary world. When she originally published MY HUSBAND in 2014, she was just 35. As I learned more about her, I came upon her engaging talk on her work and her life. Bužarovska’s excellent articulation in English made me wonder if she’d write equally effortlessly in both the languages. This story collection was published in Croatian as MOJOT MAZ, and it won the Edo Budiša Award for the best short story collection in 2016.

What makes Bužarovskaj’s stories so relevant at any moment in time is the burning focus on the splintering of an intimate relationship. MY HUSBAND places us in the middle of that hairy and uncertain place that many marriages invariably reach, when disenchantment nips at our synapses during our moments of solitude: The children have been ushered in, the sexual excitement is long past, daily life is now a grind and the future guarantees only more ennui. How many of us will even dare admit we’ve been there?

Life with Boban was pleasant but dull, to the point that sometimes when I could see he wanted to make love, I took my time doing the dishes to avoid going to bed with him. So long, in fact, that in the end Boban often fell asleep. I felt bad about doing it, because Boban was always gentle with me. But I hated pretending that I enjoyed it. Once Boban suggested we buy a dishwasher, but I told him I wouldn’t hear of it, claiming that not only does it consume a lot of electricity, but it doesn’t wash the dishes properly; things I knew weren’t exactly true.

What I found especially intriguing was the relevancy—both universal and specific to the locale—of these stories. North Macedonia, officially the Republic of North Macedonia, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe. Macedonia represents the melding of the major cultural traditions of Europe and Asia. It shares land borders with Kosovo to the northwest, Serbia to the north, Bulgaria to the east, Greece to the south, and Albania to the west.

Of course Rumena Bužarovska’s portrayal of North Macedonia is bleak for it’s clear that patriarchy is alive and well. If the men are full of it, the women are at least almost as unpleasant. I didn’t feel sorry for the women. They’re whiny and rheumy and it takes most of them a while before they react effectively to the situation at hand. Patriarchal attitudes prevail also because there is no army of women out to crush the forces. Instead, women often employ expedient measures in an attempt to buy peace and save their marriage.

In Adulterer, a terrific story about a wife confronting her husband about his clandestine affair, the wife’s mother makes it clear just how her daughter must handle her husband’s infidelity. The end is smart and funny as the woman takes her mother’s advice.

“Pull yourself together,” she said to me. I tried to do as I was told. Her red lipstick was slightly smudged on the right side of her mouth and her mascara had run a bit below her left eye., clumping in the wrinkles under her eyelashes. She was holding a nail polish brush in her long bony fingers. She started polishing her nails as I told her what had happened.

“He’s your husband. You chose him, so you have to put up with him. Divorce is out of the question, “ she said, blowing on the red polish that coated her long pointy nails. “You can’t kick him out because he may never come back,” she said, looking me in the eye. “Listen to me, darling. I’m talking from experience. She’s the one who needs to go.”

Bužarovska often taps into what centuries of clashes and conflicts has wrought in the hearts of people of the North Macedonian region. Although the majority of the republic’s inhabitants are of Slavic descent and subscribe to the Eastern Orthodox tradition of Christianity, the five centuries of the Ottoman Empire saw the proliferation of ethnic groups. We see Gene—so brilliantly named—who cannot see past people's skin color and heritage until, in the end—enabled by the sly stroke of the author’s pen—we begin to see how every one of his prejudices is examined afresh by the sudden twists in his life.

He had a “theory” that every ethnic group had certain genetic traits that made them behave in particular ways. Polish women were “greedy,” for example, while American women were “proud.” Macedonian women made the best wives. Montenegrins made the worst. But the vilest things he had to say were about the Greeks and the Albanians, or “Shiptars” as he insultingly referred to the latter. He despised the Greeks wholeheartedly, though he had little specific to say about them other than that the men where short and dark skinned, while the women had “big butts.” More generally, he referred to the Greeks as “history’s thieves.”

Passages such as the above are vile but they’re as real as anything I’ve experienced in real life. Bužarovska manages to make such passages sing and sting. I recognized right away the insidiousness that lives deep within all of us and causes us to judge, decry and vilify the other.

In the final story of this book, The Eighth of March, two senior professors invade the privacy of a young colleague named Irena. They sanctimoniously needle her for living together with her boyfriend and not committing to marriage. For Bužarovska, this seems personal and in this interview for Calvert Journal, she claims to have endured all sorts of taunts and provocations as a young woman. She packed The Eighth of March with some of what she suffered when she was a young woman like Irena. Bužarovska avenges all the insults she endured by poisoning (food poisoning) the two main characters in the story. The senior colleagues abscond together on an ill-fated tryst at Mount Vodno where they face their karma. In a tragicomic denouement, we begin to experience the truth of every intimate relationship. It’s beautiful. It’s ugly. It’s fake. It’s real. It’s sad. And it’s so hellishly funny.

“Christ!” Tony screamed. “What have you done? Get out of the way!” he said, shoving me aside as he squirmed out from under me with his pants down around his knees. He dragged himself over to the other side of the seat and kept as far away as possible from me. I opened the door. Crouched on my knees on the back seat, my head outside the car, I couldn’t stop vomiting. Every time I thought I was done. I’d lift my head, straighten up, but then once again get a whiff of the smell that had hit me in the face and start retching and puking bile.”

So beautifully written Kalpana. I see a profound change in your writing and insight as you open the doors of these books for us!! Thank you 😊

When I read your title in the email, I flinched on behalf of your actual husband: a tmi ‘stack? No! It was about a bunch of guys who make the rest of us hubbies look pretty good. Whew! Thanks for that!