STORIES FROM ASSAM

All of Assam’s beauty and unrest are packed into this collection of tales by a prominent Assamese writer.

Some books have invisible claws. Among the translated books I read over the last year, a few come to mind that seem to sport talons unseeable by the human eye: Poonachi (Tamil), The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die (Bengali), Time Shelter (Bulgarian), Empty Wardrobes (Portuguese), Masks, (Japanese), Mai (Hindi), Caught With An Unopened Umbrella In The Pouring Rain (Romanian), The Museum Of Innocence (Turkish), My Brilliant Friend (Italian), and One Hundred Years of Solitude (Spanish).

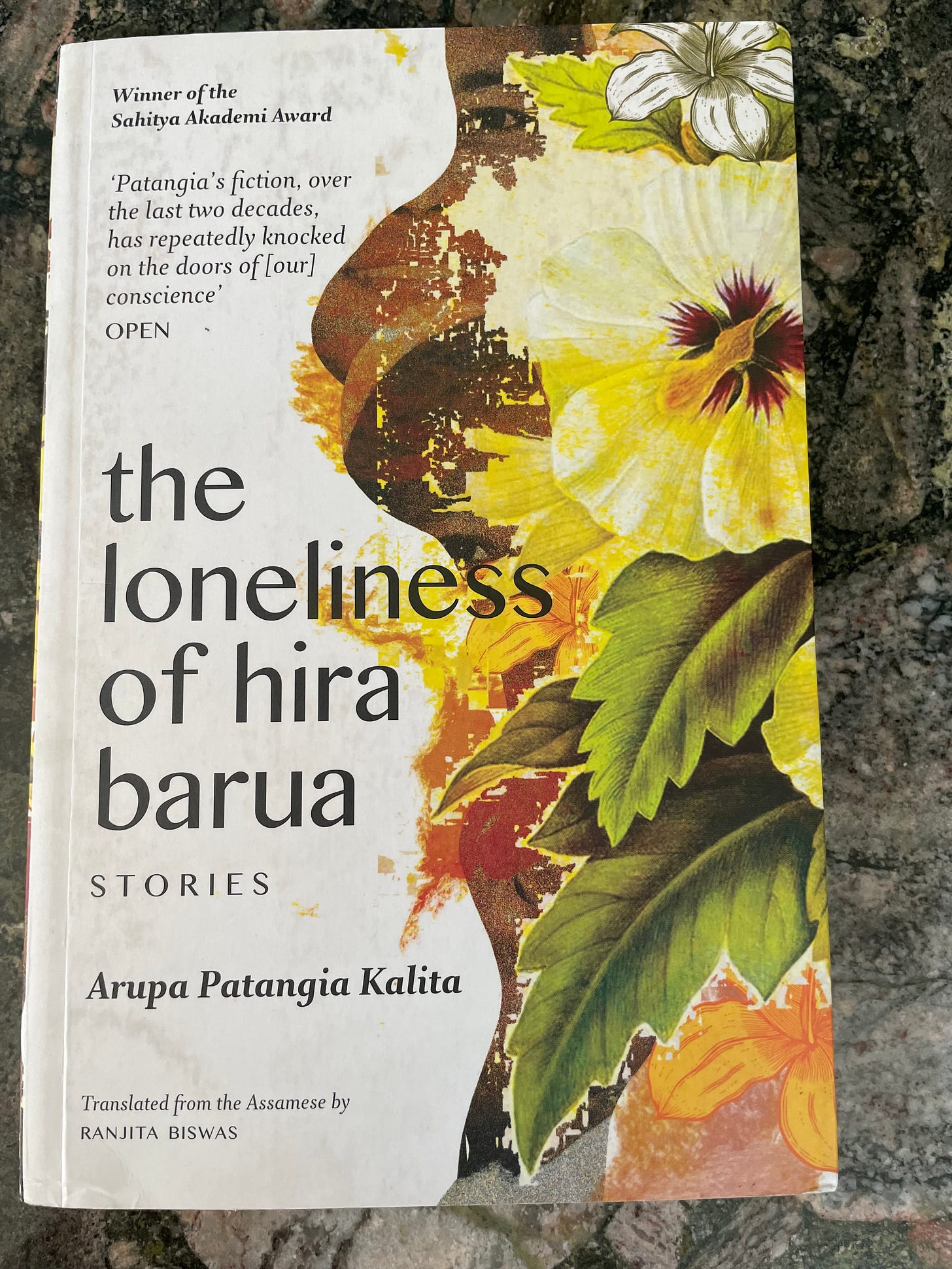

While I don’t think I’d add The Loneliness of Hira Barua by Dr. Arupa Patangia Kalita to that list of mine, the stories she tells are powerful. The sense of place in her work took my breath away. Her narratives are unique to the northeastern region of India, Assam, an area rife with unrest. Like the rivers that meander through the villages described in these tales, the characters, too, have a way of worming their way into one’s heart. Considered one of the most prominent feminist writers from the North-East, Kalita is celebrated in Assam as a “powerful storyteller of topics, such as insurgency, poverty and women’s issues.” She received India’s Sahitya Akademi Award in 2014 for her acclaimed novel, Mariam Austin Othoba Hira Barua.

Assam has been a site of migration since the Partition of the subcontinent. From Bengali Hindu refugees arriving during and shortly after the establishment of India and Pakistan, to the exodus of people from the neighboring regions flooding in through what are perceived as porous borders, the state has endured a spate of challenges owing to its geography and, of course, the weather. Assam is battered by seasonal floods. In the rainy season, the Brahmaputra and other rivers flood adjacent lands, washing away property, bridges and railway tracks including houses and livestock. Assam’s lush beauty, the unpredictability of life in these parts, and the state’s proclivity for violence inform the stories in The Loneliness of Hira Barua.

What also grabbed my attention in her body of work—over twenty novels—was her interest in translating into the Assamese language. Kalita has worked on a translation of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, besides translations of collections of Russian and Chinese folk tales.

More and more, I’m beginning to understand how a sensitive, articulate translator can pack me into a hand-drawn rickshaw and cart me off into the world of the story. When that does not happen in a translation that I’m reading—and I begin to watch myself turning the pages to see when the story will end—it’s clear that more fine-tuning would have helped the narrative. Despite that feeling while reading this work, I found myself both moved and taken aback as some of the stories rolled to a close.

Among the most poignant stories in the book is the eponymous short story featuring the aging Hira Barua, a widow living in a conflict-ridden region of Assam with her beloved Tibetan spaniel. As time wears on, she sees herself resembling a lonely Englishwoman that her late uncle described when she was a child. The hardest thing in the world, especially as we grow into our twilight years, is to confront and accept our invisibility. Hira Barua’s loneliness stems from wanting to feel needed. While this story felt bloated and ponderous in parts, it was loaded with significance, with one clear message: The day we begin to be irrelevant to others, life will cease to hold meaning.

No Escape From Hell is a tightly-written tale about the ways in which aspiring to the modern life is often tantamount to demolishing old values. A college-going son wants a motorcycle when his father cannot even afford to pay for his wife’s medical treatment. It’s clear he might even kill his father to get what he needs. Such are the times, when the rage and disgruntlement of life on the edges of town seep into life inside the home.

The parents had often passed by the showroom on the way to their offices. That corner used to be a kasuoni full of long yam plants that thrive in watery soil. During the rainy season the water drained out to the low-lying area. The leaves of the yam plants remained almost submerged during this period, but the road remained unhindered even during the heaviest monsoon. Without anyone noticing, the kasuoni disappeared one day.

What happens when old values clash with the new? Is there any point in rebellion? In the story, another father who watches his spoilt daughter shack up with a rich man’s son tells his wife that the only way to be is to keep doing what they’ve always loved to do. The point of this narrative, I believe, is to keep perspective. We cannot change anything but ourselves.

One of the most gripping stories in the book is The Half-burnt Bus at Midnight in which the author takes us, literally, on a bus ride through the stunning Assamese countryside.

The little town begins where the row of simalu trees end. The little river girdles the town—flowing serenely by the backyard of a house, the window in another, even the front doors of some other houses. At the crack of dawn, when the sky awakes in a flush of pink, schools of small jaoria fish too wake up in the stream only to disappear underwater as the day gets brighter. The river keeps the town well-watered and the trees a lush green. Upstream, the river starts playing hide-and-seek among the emerald carpets of tea bushes, then gets slimmer and swifter, and ducks for cover at will.

We screech to a halt, however, right in the middle of this breathtaking ride. We discover, soon enough, that we’re actually perched on a roller coaster seat (with a scenic view) that’s about to be hurl us into hell: A half-burnt bus is passing through this city charring everything alive and beautiful in its wake. We won’t know why until the very end. No spoilers here, I promise.

But the bus went on, that half-burnt bus. The black ash made the mud sticky. The frogs living in the field perished; their white bellies lay upturned to the sky. They started giving out a putrid smell that filled the air, making it unbearable to breathe.

Books like The Loneliness Of Hira Barua must exist, even if they don’t have the “claws” I alluded to at the beginning of this post. They remind us that remote places like Assam must be part of the conversation. This review of an Assamese poetry collection in the Chicago Review of Books comments on how the British colonial government viewed Assamese land tracts as terra incognita until the late-nineteenth century. Not much has changed in independent India, it seemst: “The post-colonial state, being what it is, has always quelled the nationalistic projects of the insurgents of Assam with a heavy hand, harsh public policies, and inimical moves.”

I found it helpful to also listen to Dr. Kalita’s thoughts on her writings at this event at the Jaipur Literature Festival. Hearing her speak about the political unrest and economic upheavals in Assam over the decades helped me see, even more clearly, the inherent value of her stories and also understand why we cannot ever forget about the people on the fringes of the nation.

While reminding us of India’s endless diversity, The Loneliness of Hira Barua underscores how the human heart rarely skips a beat. The people are the same, after all, from one end of India to the other end of the world.

Well, this is a great thought beautifully expressed: “a sensitive, articulate translator can pack me into a hand-drawn rickshaw and cart me off into the world of the story.” Meanwhile, that bit about “the day we begin to be irrelevant to others, life will cease to hold meaning” was a reminder: fight irrelevancy! It may be why some of us write: to widen the circle of people who notice us, and continue to care.