STOPPING BY THE MORISAKI BOOKSHOP

An introspectiveJapanese book about a bookstore led me through the life of bookstores that ultimately become local institutions.

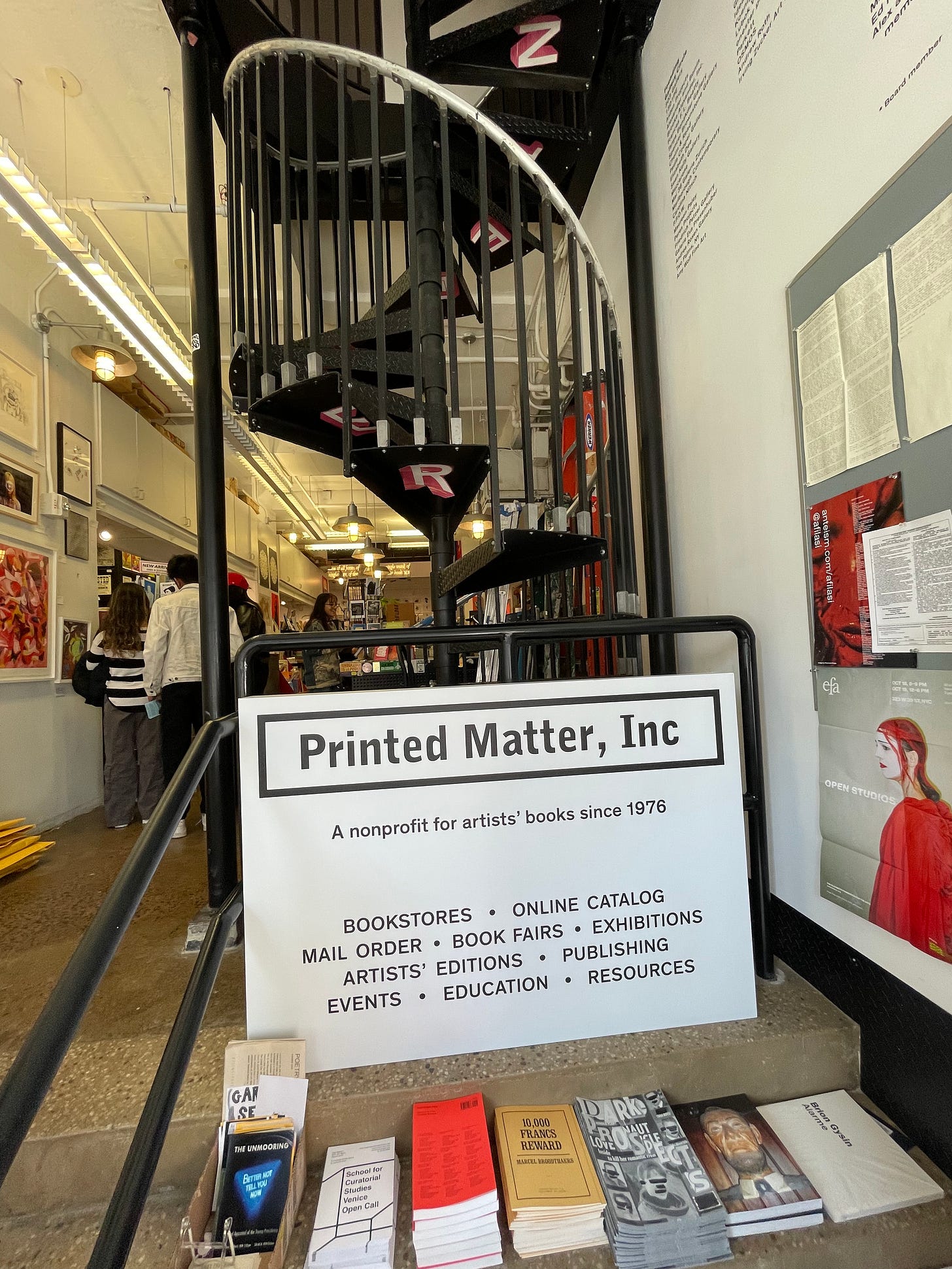

What I love about my weekly readings is the surprise that’s held in each week’s pick. Last week’s The Vegetarian was intense. In contrast, this week’s read was a quiet, laidback read that I happened upon in a quaint Manhattan bookstore called Three Lives & Company.

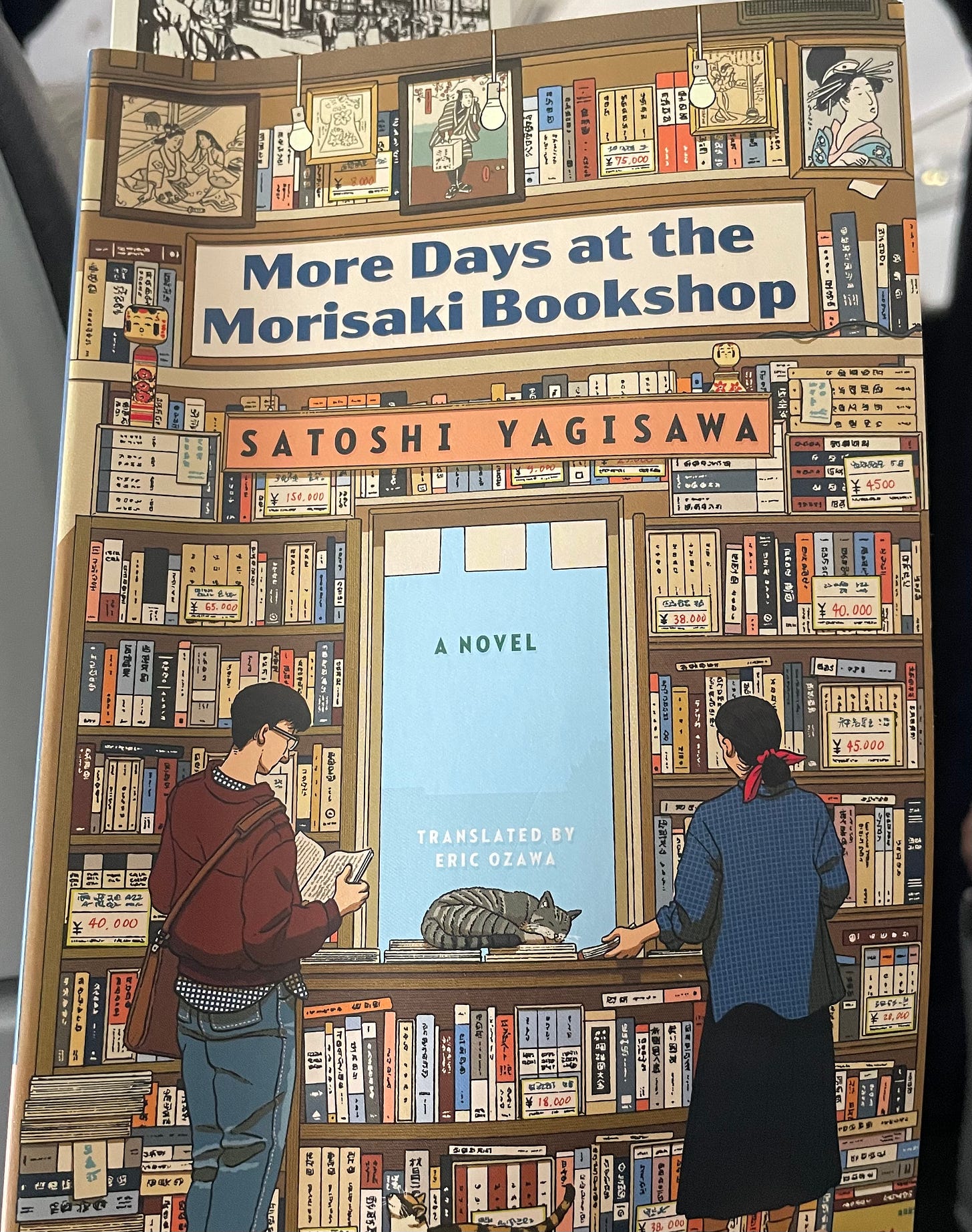

More Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is a meditation on relationships and the books we hold dear through the course of our lives. This book follows an award-winning debut by the author titled Days at the Morisaki Bookshop. Not having read the first novel by author Satoshi Yagisawa, I hadn’t already met the woman called Takako. She is the niece of a man called Satoru who has devoted his life to the bookshop that has been in his family for several generations.

Hidden in the Jimbōchō neighborhood in the city of Tokyo, the Morisaki bookshop is a book lover's paradise that has been curated with love and sweat. It has hummed for decades on a quiet corner of the book district in an old wooden building. It turns out that Jimbōchō is not just a figment of the author’s imagination; it is one of Asia’s bookish neighborhoods known for bookstores specializing in a variety of specific genres, such as classic literature, philosophy, art, pop culture, science, foreign and rare antiquarian books. Just as in many of the new and secondhand bookstores in India, these shops display their discount items on open-air bookshelves, luring bibliophiles in with that distinct scent of well-aged paper.

His Morisaki Bookshop is an old-fashioned store, in a two-floor wooden building untouched by time, every bit the image of a vintage bookshop. The inside is cramped. You could get five people in there, but just barely. There’s never enough space on the shelves; the books are piled on top, and along the walls, and even behind the counter where the cash register is. And the intense, musty smell particular to old bookshops penetrates everything.

We learn that there was a time when Takako never liked reading even though the Morisaki bookshop had been in her family for generations. When we meet her as the book opens we discover that she has now found peace and joy as a reader. What also seems to excite her as much as the experience of reading itself is watching how visitors to the shop pick their books. Some visitors are regulars and they make a beeline to a specific shelf piquing Takako’s curiosity as to why they’re drawn to a specific work. Her uncle tells Takako to never question why someone is interested in something and that detachment is something he has practiced for years.

“Hey,” He spoke in the tone of voice you use to reprimand a child. “Your job isn’t to start getting so nosy about the customers. The purpose of a bookshop is to sell books to people who need them. It’s not right for us to start wondering what kind of job people have or what sort of life they lead. It’s not going to make these older customers feel very good if they know the salespeople have been prying into their lives.”

More Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is the fifth book I’m reading in translation from the Japanese and through these works, some things have become clear about the ethos of the Japanese people. They come across as a quiet introspective lot who value old things that are imbued with meaning and significance. They also seem to hold a lot deep inside them and let very little leak into the world. I sense a a quiet stoicism about a large swath of characters that populate these books, as if suffering in silence were really the only way to be. This week’s novel, too, conveys this idea, with the harried bookshop owner, Saturo, being the classic representative of a Japanese male in his fifties whose wife has just recovered from a serious bout of cancer.

We learn that Saturo himself underwent a serious transformation in his twenties, when he fell out with his parents (Takake’s grandparents). As Saturo matured, the bookstore that he inherited began to hold meaning for him as much as the contents themselves. In Takako’s eyes, Saturo is a walking encyclopedia on Japanese literature, and, naturally, readers of this book are party to intriguing discussions about the lives and works of Japanese poets and writers.

My uncle knew an extraordinary amount about Sakunosuke Oda—his whole life, not just his books. When he liked a writer, he loved nothing more than to read their autobiographies, memoirs, biographies, collected letters, etc. It had nothing to do with the business of running a used bookshop. He did it purely to satisfy his own interest.

This aspect totally resonated with me, that when we come upon a writer whose work we love, we want to peek into their lives to make connections between their life events and the works they produce. This is also why I love talking to those who run old, historic bookstores because they’re such a fund of information. In the novel, we can see that Satoru is interested in grooming his niece even though he doesn’t exactly say so.

As the seasons change, Satoru and Takako face the greatest challenge of their lives, the impending death of someone they both love dearly. More Days at the Morisaki Bookshop is about how both niece and uncle lift each other up through their sorrow and return to open their bookstore after they’ve buried their loved one.

The Morisaki bookshop is a force in this moving tale for it has something to say to both owners and visitors about life, love, and the healing power of books. I found out long after I closed this book that its author Satoshi Yagisawa is a musician. I learned that Satoshi’s compositions for wind orchestra are popular in Japan and many other countries. It all made total sense as I thought about the beautiful, universal story that resonated so deeply with me.

A writer I like left behind a passage like this in one of his books: “People forget all kinds of things. They live by forgetting. Yet our thoughts endure, the way waves leave traces in the sand.” Deep down I hope that’s true. It gives me great hope.

A plane crosses the sky in the distance, leaving behind it a freshly born cloud.

“Hey, Uncle, see that cloud behind the place?” I pointed to the sky, and my uncle looked up and squinted at it.

The cloud kept growing longer, drawing a bright white line all the way across the pale blue sky.