SO SLY AND SUBVERSIVE

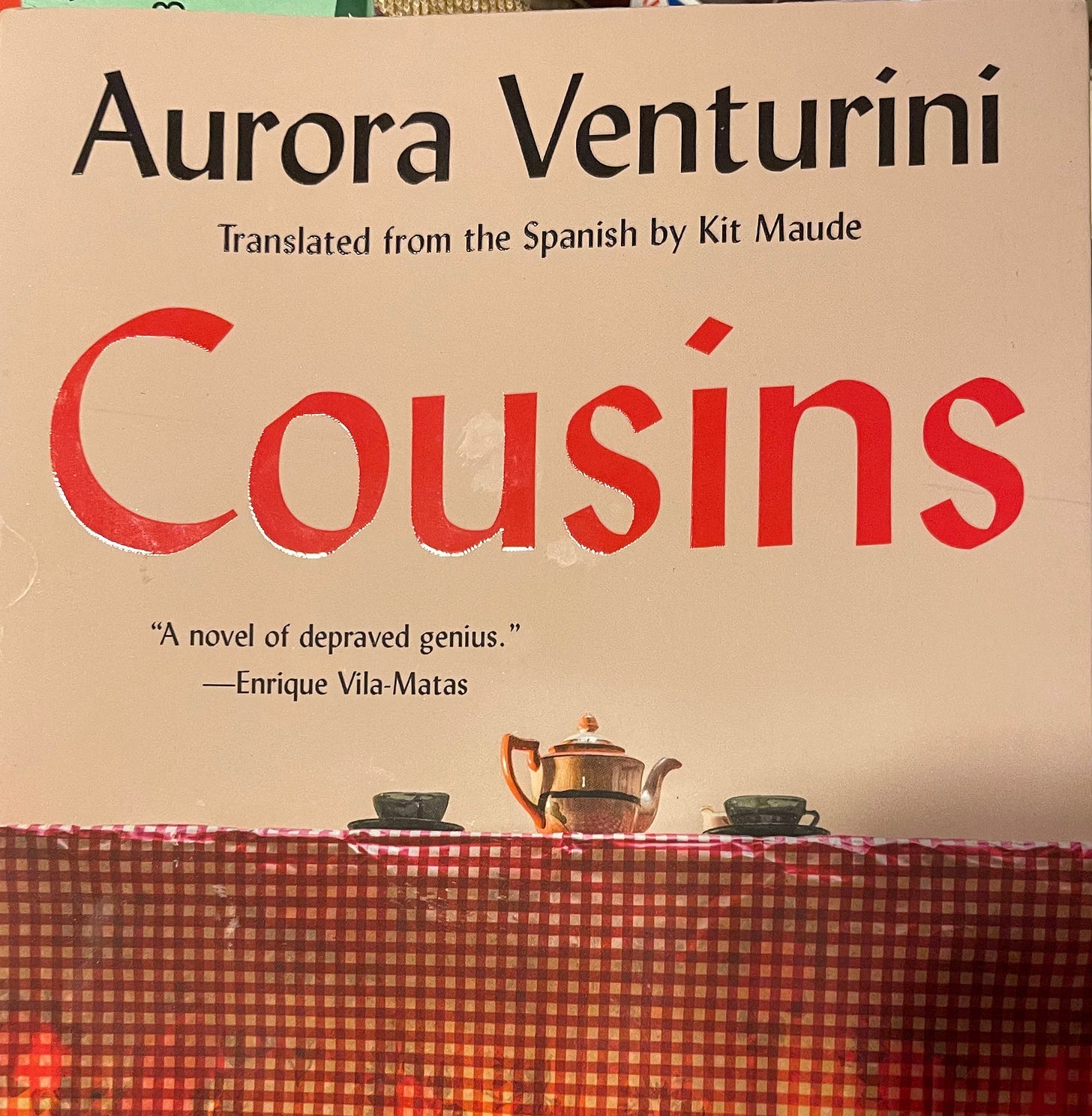

COUSINS made me want to retch, laugh and weep. I was putty in the hands of this masterful Argentinian writer named Aurora Venturini. What a great gift from my local library on my birthday week!

Behold two odd female cousins, the strangest ones I’ve encountered in fiction. Petra, the diminutive one, the “dwarf”, knows everything about everything (with extensive on-the-job training in oral sex); the other one, the tall girl, is the genius Yuna, who is 5’ 6”, who, while inarticulate, is a virtuosic painter who takes pity on the cousin who knows everything about everything. The brilliant Aurora Venturini buries us so deep in the head of Yuna that it’s only in the last page that we acquire some peripheral vision and begin to see things in black and white. The main characters in this manic story about a dysfunctional family reveal their true selves to each other by the end by when it’s also clear that the author is the wiliest of all.

The author’s own professional life seems to have informed her work in the novel. Born in 1921 in Argentina, Venturini worked as a psychologist and Rorschach test specialist at the Institute of the Child's Psychology and Re-education in Buenos Aires. In 1948, Jorge Luis Borges awarded Venturini the Premio Iniciación for her book El Solitario. Persecuted for her political ideas, this friend of Eva Peron sought exile in Paris where she interacted with personalities well-known in French existentialism. This prolific author had more than thirty books to her name but she was 85 years of age by the time she received the Página/12's New Novel Award for COUSINS in 2007. She died eight years later, in Buenos Aires, at the age of ninety-four.

COUSINS is a story about an unpleasant family that remains unlikeable throughout. It’s not just that the characters in the story all skew against the grain of what we in the world consider acceptable or normal. There is neither love nor affection based on genuine feeling. Yuna and Petra, the two main cousins of the narrative, are the only two who demonstrate enough sensitivity to be deserving of our interest and attention.

It doesn’t take long for us to see that all the inbreeding of cousins may have resulted in offsprings being “abnormal” as Yuna herself notes in her moments of clarity. Like Petra, Yuna is a survivor, too. She learns to accept the disabilities of her sister and fights for her rights, too. By the time she becomes aware of the world around her, her father has abandoned them.

Who is worthy of their reverence? Who is the father figure whom they can trust? Not even one, we find out, over the course of the tale. Her maternal uncles are hopeless cons, too. All the men in COUSINS are depraved or nincompoops at best. If misogyny visits Yuna’s home long before she is her own person, she does not also recognize the endless manipulation by those closes to her.

Of the two cousins, Yuna is clearly more honest as well as more trusting. Even though her speech is ill-formed, her intellect and the expression of her cerebral might are striking. The only redeeming quality of Yuna’s life is her extraordinary talent as a painter, a gift that gushes in a torrent out of the depths of her being. Given Yuna’s acute intelligence, she learns rapidly.

I was equally dazzled by Venturini’s mastery over craft throughout. While also advancing the story at a fast clip, Venturini manages to shows us the pace at which Yuna learns. Venturini conveys the goop inside Yuna’s pretty head on the printed page while simultaneously showing how the goop translates into an arresting image that invariably takes the international art world by storm.

There is a passage that describes how Yuna portrays her cousin’s clandestine “abortion”, a word that is inducted into the ever-expanding dictionary of her mind by her all-knowing little cousin, Petra. How can anyone not be moved to tears by such an illustration?

I painted a map of the world on a big piece of cardboard with a tadpole floating inside it, striving to protect itself from a trident that was trying to skewer it and suddenly the tadpole looked like a human seed, an ugly boy that grew cuter every minute until it was a baby and then the trident pierced him in his little belly and he floated outside the map of the world.

Yuna’s prescient gift soon becomes a magnet not just for her teacher, the man we know of as “Professor”, but also for other members of the family. She brings in money. She puts food on the table, as does Petra, too, by way of her talents of which, the less we say, the better. Still, Petra is a survivor, one who crawls and slithers her way out of the bog. It’s hard to not admire her pluck.

At the heart of COUSINS is a question as to why a woman would even want to trust a man. The men in the story are either leeches, predators or master manipulators. Clearly, the only way for a woman to get ahead is to be so excellent at what she does that the man is made redundant in her life or to make a man endlessly suck up to her.

As I neared the end, I wondered why a novel like COUSINS had not reached the rest of the Anglophone world. There are, literally, no analyses of a book that’s deserving of them . Where are the reviews? Where are the discussions? Had this book been conceived and birthed in the world of English, I have absolutely no doubt that its reception would have been completely different.

I did happen upon this terrific interview of the translator Kit Maude that I found so enlightening. I had wondered how the translator had even managed to decipher and translate a novel in which the narrator is unable to navigate through her story with clauses, commas and periods, owing to her peculiar condition.

But each of us is how they were born and you just have to put up with it the way I put up with the fake surname of Riglos which the professor known as Don Jose Camaleon or just Jose, put underneath my paintings. I can’t get used to seeing him in his shirtsleeves reading; the newspaper or drinking mate as if he owned the house and although it seems rude I say try to myself that that role belongs to my father who lost it because he abandoned us but I have no right to ask things that are none of my business and also I was the one who first brought the professor home when we were poor and the house didn’t have a backyard with a barbecue pit and Petra wouldn’t be able to roast meat and delicious chinchulines when she got back from the oddest profession, and other times, too.

By the time we roll towards the closing chapter, it’s obvious that both Petra and Yuna have their god-ordained areas of talent and strength and that the only way for them to get ahead is to enter a man’s world in their self-directed way.

When at last I turned to the closing page of COUSINS, I recognized how even while I was rendered speechless, Yuna did, in fact, find her speech—and herself, too, I might add—and encapsulated her thoughts in wholesome, loopy sentences marked up with the tidiest punctuation, too.

We started to eat dinner and Carmelo praised the ravioli for which Petra said she’d made the vegetable filling herself along with the sauce but I knew that in the trash bag was the box of store-bought ravioli and the little carton of sauce and sensed that the Lilliputian whose mischievousness was several feet taller than she was was plotting something and Carmelo took some bread from the basket and dipped it, praising the flavor which he said reminded him of the sauce his mamma italiana made because the Spichafocos were Sicilian and very fond of pasta, and he eagerly devoured the culinary masterpiece by Petra who didn’t know it was dangerous to lie to a Sicilian, even if it is only about pasta.