SO MUCH BEHIND THAT STILL LIFE

I read one of Natalia Ginzburg's novellas—FAMILY—in 95% humidity in Kerala. The story felt as opaque as the skies over the backwaters until, in the end, the sun shone through.

I’ve been unable to give exclusive time to reading when I’m on a trip. Here in India, I pack my life with a million daily activities. There are aging relatives to see, temples to visit, concerts to hear, saris to gush over and bookstores to stop at. I must forge new connections, too. As it happens so often during travel, if I don’t pack it all in, nature packs it in for me. I arrived in India on December 1, and as I said in my last post about the cyclone in Chennai, I was marooned, for about 48 hours, in a dark apartment in Chennai with no power.

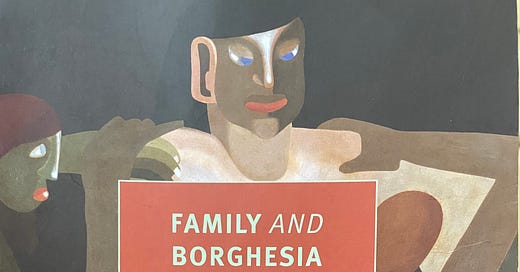

The week following the cyclone brought some exciting travel to the backwaters of Kerala for a destination wedding. Reading suffered yet again, of course. However, I picked for this weekly read a novella called Family, a strange novella about families artificially wrought by couples who seemed destined to unite only to produce a human being. People change, however, and our own perception of them changes as we trace their back stories.

I’d been reading adulatory reviews about Natalia Ginzburg’s prose for a while and it seemed a rather appropriate choice for a book while communing with family in India. This is a book about the “family” that parents build for themselves and their children. It’s also about all the other people who walk in and out of our lives. Little do we understand the prominent role that people play in our lives, at critical turning points, that affect who we become many years later.

Right at the outset of Family, we are introduced to the teenager Angelica, whose band of hair falls over her eyes preventing her from ever seeing the world clearly. This is a great metaphor for the entire world of the story in Family. No character within this novella has the sagacity to understand the larger story of his or anybody else’s life. They’re caught in the day-to-day annoyances and frustrations, helpless against the onslaught of what destiny has planned for them, and always dragged by circumstance towards the next big upset of their lives.

I didn’t find Ginzburg’s work gripping enough from the point of view of craft. That being said, I will say that she—like my mother-in-law whom I’m currently visiting—is a storyteller you’ll be listening to until an earthquake or a tornado ends it all. Ginzburg is that kind of Scheherazade.

Reading Ginzburg sometimes feels like reading a grocery list because so much on the page is a laundry list of things that people do as they go about their lives. Yet there are earth-shattering short conversations that break the monotony of life that, in real life, might have us doubling over in laughter, such as this line told by a woman who had a child with a man who married a woman who cooks like a dream: “I don’t care a fuck about aubergines in oil.” Thus Family is full of the mundane in which some unbelievable happenings insert themselves.

Ginzburg is a storyteller who will not skip a single detail, however insignificant it may ultimately be. Like my mother-in-law and her son, she will make peregrinations around other unimportant ancillary points and return to the main story with one standard line: “Where was I?” Hence we watch the story unfold with all the small and big events thrown into the passage of life. As I said before, there was always a line of a paragraph that did me in. Like this one here.

Ciaccia Oppi had a thousand ears, and nothing ever escaped her where love affairs were concerned. They were the only thing in the world that really interested her. She thought the world very boring, but thank goodness, there were love affairs, eternally beginning and ending, performing arabesques and pirouettes in the universal dullness.

It’s never clear what the purpose of a family is that has been created out of what seems to be just thoughtless, momentary madness and lack of forethought. The progeny from such a union. Are they also unfortunate by-products of a certain lack of vision and planning? That is how it seemed as I snaked farther and farther into the story, uncertain of where I was being ferried and why I was being led into the depths of murkiness. Still, by the time I reached the end on page 68, I was invested in the characters and was anxious to know what would happen to them.

A terrific afterword by Eric Gudas brought clarity to several aspects of this windy story. Gudas expressed something that I’d never ever been able to articulate as well. It’s this idea that when we’re caught up in the living of our lives, we’re often bored of it all while we’re in it. Still, does that mean we are not happy? The essay by Gudas shines the light.

Ginzburg’s characters often describe themselves as “bored” but as she wrote in an essay from the 1960s “boredom does not exclude happiness. They can coexist and can join together, inextricably tangled.”

Performing arabesques in the universal dullness. Now there’s a life purpose!