SO COCKSURE ABOUT THIS ONE

This hilarious little book in Malayalam is so good that you'll want to crow its name from your rooftop.

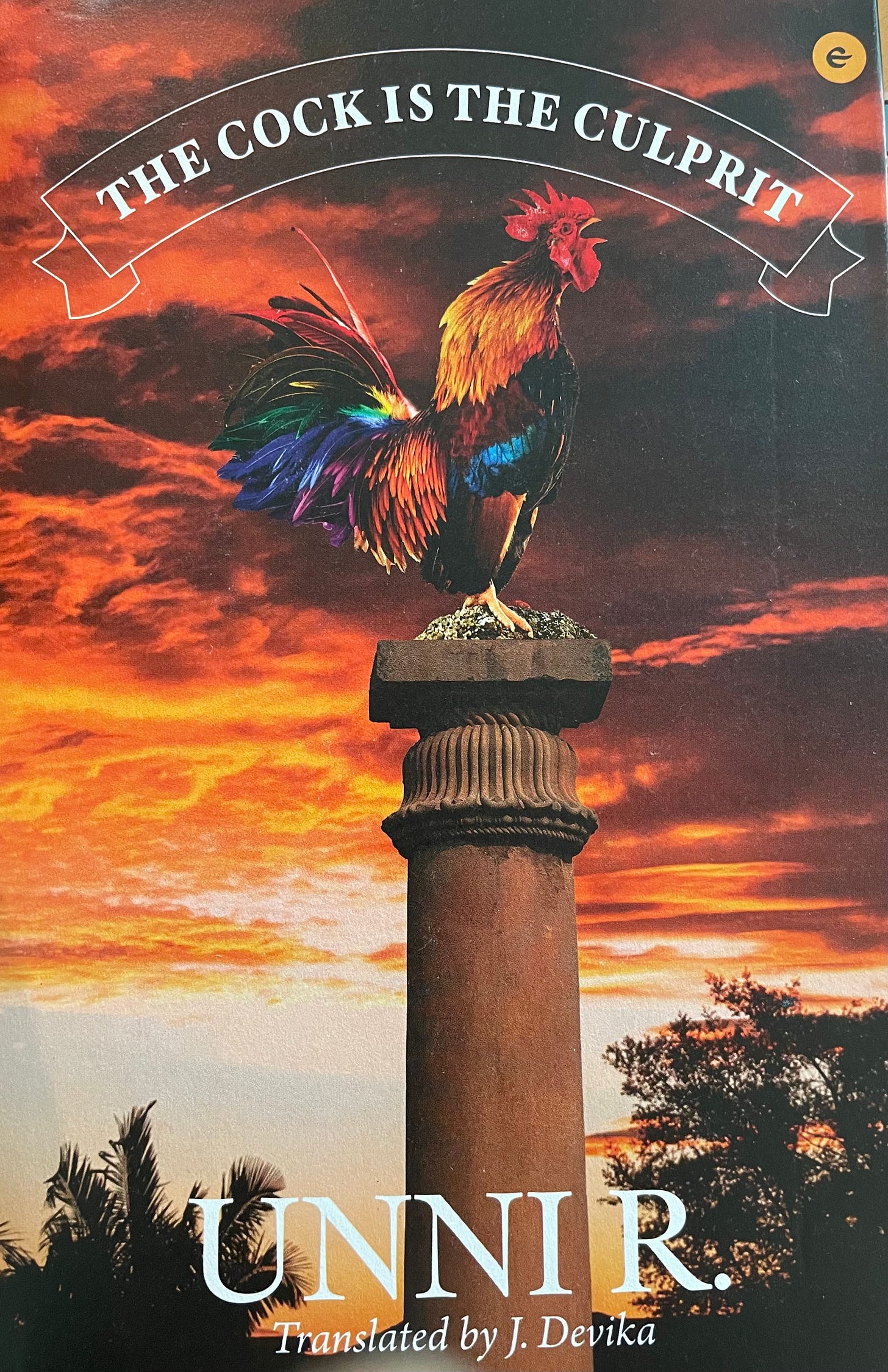

Its cover is striking. A rooster stands atop the capital of what resembles an ancient Ashoka pillar. The tale itself begins with so much clarity and finesse that I sensed that what I was holding in my hands would be a delight through and through.

Kochukuttan had this thing about early mornings—he would lie quietly in bed, half asleep, half awake. That’s the hour in which the past arrived unsieved by age, the times, day or night.

I loved the opening. When we emerge into wakefulness early in the morning, we’re in a liminal state—between the peacefulness of sleep and the unpredictability of the day. Our thoughts are untainted. Things tend to swim into great focus right then, just as the author suggests.

The Cock is The Culprit is a debut novel by writer Unni R from India’s Kerala. Illustrated by Riyas Komu, it was translated from the Malayalam language by J. Devika and published by Eka publications.

We see the events in the village through the eyes of Kochukuttan, a young man born into a low caste who lives with his working class parents. It begins simply enough. A rooster has been crowing at critical moments in the village. It crows during Nirmaalyam, the most auspicious moment signaling the start of the day’s activities at a temple. It skreighs when a flag is being hoisted. It screeches during offerings at church. It squawks during political meetings. The entire village is flummoxed by this creature. Soon, plans are afoot to kill it.

“That cock is making everybody’s life miserable. Can’t you get rid of the whole thing by doing what Kurup saar suggested?”

“Doing what?”

“Unmoolanam. Annihilation. Extermination.”

Oddly enough one man is skeptical about the happenings. Kochukuttan—who has applied for a visa to find employment in the Middle East—has a lot of questions. He does not understand why the police and the powerful people in cahoots with them want to kill the truant bird. In Kochukuttan’s view, the bird belongs to Naniyamma, a deaf old woman, and no one has the right to snuff it out. As far as he’s concerned, a rooster also makes every day count.

Anyone with some common sense should have been able to see that there is no fixed time for cocks to crow. There’s never been a dawn that did not brighten because the cock failed to crow. Neither the mornings nor the sun have suffered any loss because of omissions on the part of cockerels.

The power of one may not be underestimated, according to The Cock Is The Culprit. It shines the torch on what can happen when one voice shrieks in dissonance in a village where the powerful collude with the police, the rich go away to America to escape their problems, and the poor continue to dither, not knowing who or what to believe. The novella is also a rebuke about what happens when people flock together and fear those who are more powerful than themselves, while never holding them accountable for their actions.

The novel is snarky, with many moments of laugh-out-loud humor. Chaakku (it means sack and in colloquial Malayalam it also means fib) is a self-serving village power-monger who made his money in jute. Upon marrying a woman in a powerful family, he decided to make a point about who he was by building a wall that shut out the flotsam and jetsam of the village. The wall separated him from old Naniyamma’s humble home.

He had burst crackers when the US invaded Afghanistan. Kochukuttan had heard from some of Chaakku’s hangers-on that he believed that the road to peace lay through war. In that case, there lived inside him a fan of the US of A. If he did indeed conduct a silent prayer for fallen soldiers, it could well have been in the memory of American soldiers. Nobody had asked him: which army, which jawans?

Over time Chaakku finds that the crow of the rooster is strident enough to make his life living hell. Still he has the means to buy the police and snuff out the life of the brassy rooster.

Kochukuttan lodges an informal protest with Chaakku. Soon, Kochukuttan becomes the target of calumny for his unpopular beliefs. He’s imprisoned and threatened and then sent home. It’s clear now that his visa to the Saudi Arabia and his future plans may be in jeopardy. Meanwhile, the menace continues; now, oddly enough, there seems to be more than one rooster causing mayhem in the village.

Besides it had come to their attention that the same horrid cackle was heard when people tried to consult astrologers about their future, when husbands yelled at wives or beat them, when men indulged in post-orgasmic neglect of their wives or lovers, and when they bragged about their family’s eminence.

While Chaakku attempts to brainwash the whole village about the bodacious birds, the roosters won’t stop crowing in derision at the oddest times. As we delve deeper into the story, it becomes clear that this is a cautionary tale about religious nationalism and patriarchy. The book offers a clear warning to us all to develop a healthy dose of skepticism, especially at a time when everyone around us peddles his or her version of the truth. Midway through this novella, we begin to see what a farcical lot these rooster chasers have become. It’s shocking that no one can see through it all except Kochukuttan and his mother. In time, we realize why the author rendered Naniyamma deaf. It seems that the only way to remain true and grounded is to shut our ears to the noise outside.

The best books are often short and tight. Every sentence has a purpose. Each line tightens the story another notch. The Cock Is The Culprit is an allegorical tale in 111 pages. It surprises and pokes throughout. There’s so much to unpack in this Orwellian tale and so many quotable lines that it must be read several times over simply to grasp it all.

As translator J. Devika says in her note at the end of the book, it is no coincidence that she chose to translate the title of the original novel, Prathi Poovankozhi, into The Cock is The Culprit, and not The Rooster is the Culprit. She conveys the challenges of translation with her discussion of the title: “In Malayalam, “poovankozhi” stands for cocky masculinity and power, but in English, it does not do so. “Cock”, however, instantly calls up the phallus and its power. This is to do justice to the powerful subtext that makes this book utterly remarkable.”

The novel brims with many philosophical moments too. Consider this line from early on. Kochukuttan has just been served roasted dried fish but he is preoccupied. Sensing this, his mother cautions him.

She said, “Either eat or think what you are thinking. If you do both together, you won’t taste the food, and the thinking won’t be good either.”

In a brilliant ending to a chapter titled “The Blunder”, the author conveys the import of his book. When the village henchmen are told that the only way to stanch the cacophony is by killing all the roosters, they listen to their masters.

The day after the census, all the cocks were transformed into cooked meat. The curry was distributed in the spirit of celebration in the premises of the panchayat office. Even then, the fact that Naaniyamma’s rooster was absent at the gathering lay undigested inside most people. The very same day, the payment for Kochukuttan’s visa reached Saudi.

This is a story for all time. Judging by how writer Unni R’s book sold 10,000 copies within a hundred days of its release, I have no doubt of its meteoric course into the shelf of gilt-edged international classics.

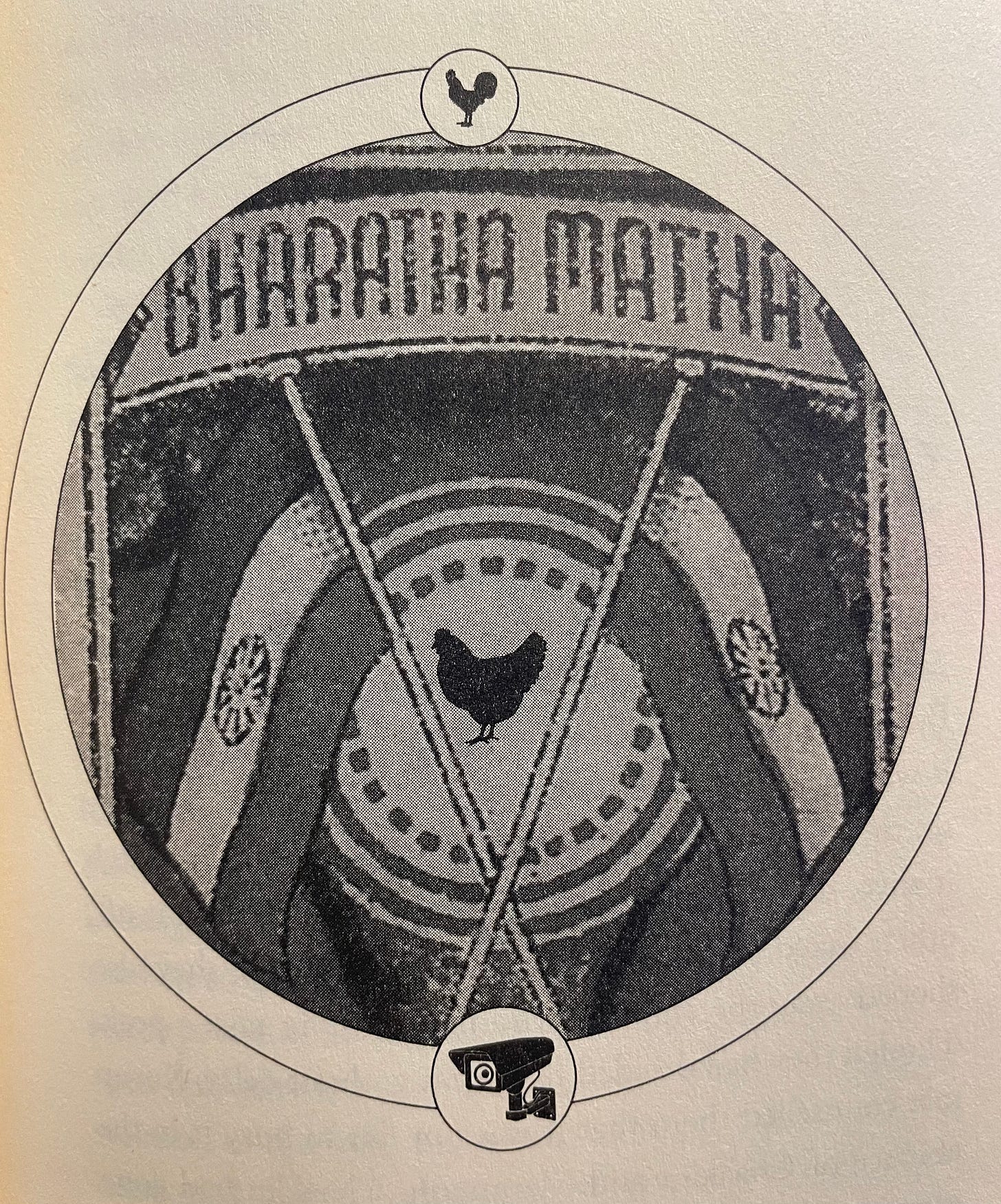

What an enchanting story! Wonder what Riyas Komu's illustrations were like ... loved the matchbox too.