SMALL STORIES, EPIC EVENTS

A reading binge has opened my eyes to some of the nuances of Southeast Asian history.

It was an evening in 2007. Our daughter was in 11th grade and I’d taunted her for spending too much energy on her history project.

“Who cares about history?” I’d yelled across the island in our kitchen. I remember receiving two earfuls right away—from both my children, in fact—about the relevance of history to them and why I, of all people, should not have said that.

When my children have children of their own, I hope they will realize why parents may, on occasion, utter things they do not quite mean. I poohpoohed the subject called history because I was then under stress, hovering over the frenetic lives of two teenagers, one 17 and the other 13, while their father was working many thousand miles away in India. For almost three years, I played the role of both parents and on some days, I failed miserably at it. I do regret the flippancy with which I dismissed the subject that day because I do care about history.

At a personal level, history attempts to answer a simple yet fundamental question of who I am. It astonishes me even as I write this, that my own history is tied so closely to a myriad people and to the different places to which I’ve belonged for a time. The list is long: Paravoor, Palakkad, Chennai, Dar-es-Salaam, Vellore, San Jose, Paris, Saratoga and, now, Singapore. I believe that to truly understand the history of a place is to also attempt to understand the many moving pieces inside it while always being aware that what lurks deep inside a place may never quite bubble to the surface unless we tune in to the locals who draw energy and inspiration from it.

When I land in a new place, I like to do a deep dive into its history by going around with local historians who often know their town so well they can take me into its heart. Such a thing was out of the question, at least for a time, when I arrived in Singapore in December. I was going to be in quarantine for two weeks. But one week into our quarantine, a friend, Seema Shah, dropped off a bag of books at our quarantine hotel. The founder of a nonprofit platform to showcase India’s heritage, Seema had a curator’s eye. The books considerably shortened my quarantine, putting me on the chase of an unfamiliar world.

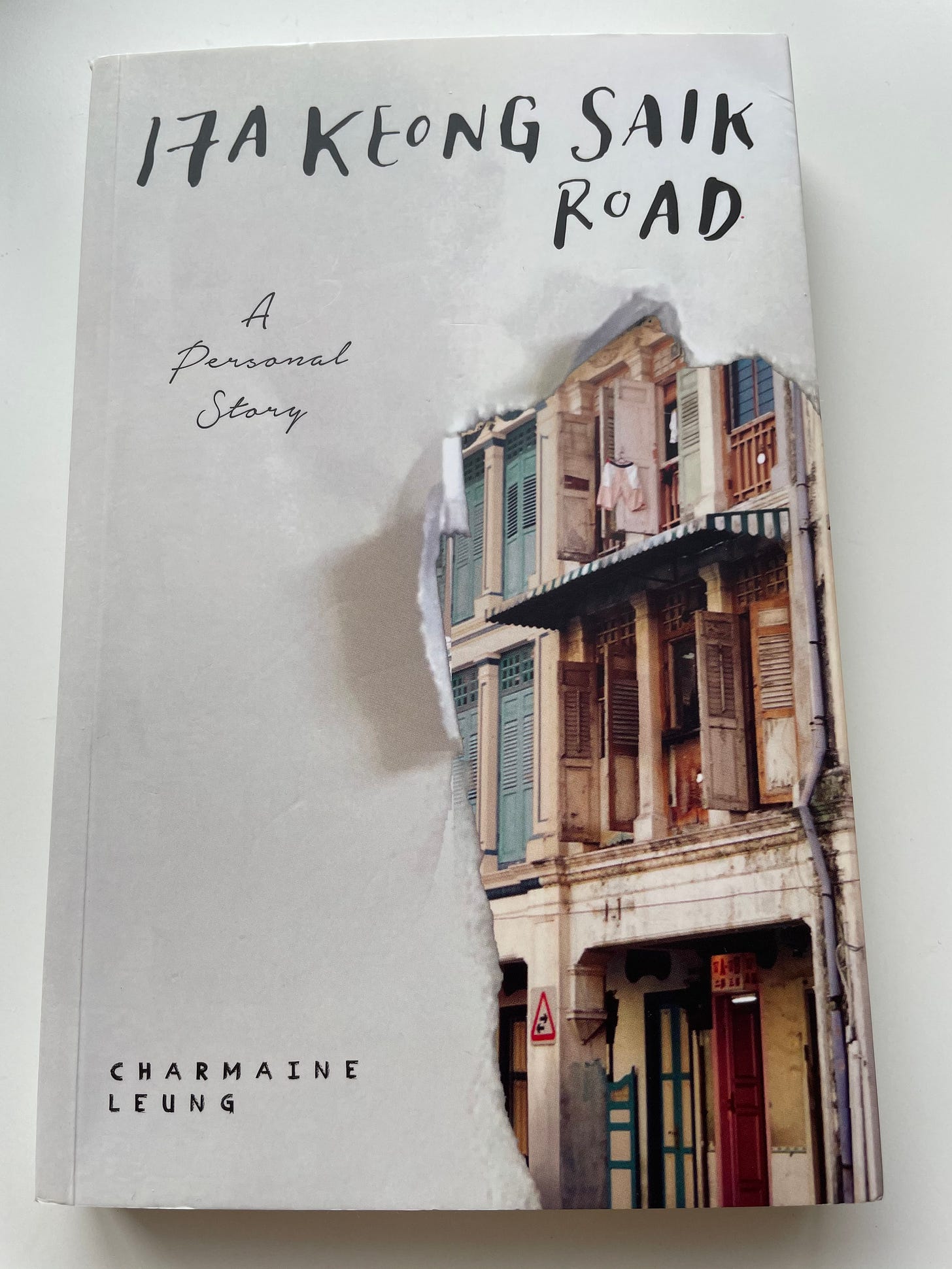

Two weeks after I finished 17A Keong Saik Lane by Charmaine Leung, I found myself at that address in the heart of what is now a gentrified part of Singapore’s Chinatown, walking past places that had once held meaning for a young Leung who could never bring herself to tell any of her friends at school where she lived. Leung was the child of a woman who owned a brothel; as a child, she became privy to a culture “where wealthy men indulged in food, alcohol, gambling, opium-smoking and entertainment by women.” Leung’s account of life in the alleyways of Chinatown in the 70s introduced me to yet another historical aspect of Chinese culture. There existed a clan of women referred to as “majie” who arrived from the southern provinces of China in the 1930s. These Cantonese women—who were celibate and spent their lives as domestic help in the homes owned by wealthy families—became the early Chinese immigrants who helped lay the foundations for Chinese culture and community in Singapore.

Even as I finished Leung’s work, I had been peeking at snatches of a second book in Seema’s collection. Josephine Chia’s Kampong Spirit (Life in Potong Pasir, 1955 to 1965) educated me about life in Singapore in the tumultuous years leading to its independence in 1965. For the most part, Singapore was a cluster of “kampongs” (or villages) with attap (palm leaf) roofs and homes on stilts. In an ambitious push to modernize, villagers were resettled in high-rise blocks. Chia’s second volume Goodbye My Kampong! (Potong Pasir, 1966 to 1975) led me through the revamping of a country that, along with India, had once been deemed a poor third world nation.

In early February, thanks to an introduction from a friend, I also sought out a local book club. Thus began a conversation with someone called Lucky who opened another door. I didn’t imagine that reading Sea of Poppies would lead me into Ghosh’s next work in The Ibis Trilogy, River of Smoke. I blazed through Flood of Fire, too, and knew I wouldn’t rest until I’d trooped through The Glass Palace. In the meanwhile, a book group in Delhi that I belong to somewhat unreliably (though they claim to like me)—had begun to read a recent book set in Singapore. Once again, the late Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s terrific memoir, The Singapore Story—that I’d been reading intermittently since early Jan—had to wait. I was now buried in Jing Jing Lee’s How We Disappeared. The natural progression (in reverse) of that story led me to The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang.

In under a month, my ever-expanding shelf of historical fiction had filled in some of the holes in my understanding of South East Asia’s history. I’d learned about how the cities of Singapore and Hong Kong were built on the fortunes of the Opium trade; those of us from India know only too well how India’s laborers were forced by the colonial rulers to grow opium in lieu of agricultural crops in order to fill the Empire’s coffers. In each of the countries ravaged by the Japanese as they chased after potential colonies to match European conquests—Singapore, Malaya and Burma—the British chose to abscond, leaving ordinary locals and Indians to fend for themselves. Amitav Ghosh describes, in gripping detail, the despair of Indian families stranded in Burma. Unable to buy tickets on ships on account of their brown skin, they trekked through a thousand miles through the perilous border terrain between Burma and India. By the close of the war, some Indian soldiers in the British Army who were torn by the irony of their situation—that they were in cahoots with one imperialist army to vanquish yet another—defected to the Indian National Army to fight on the side of the Japanese.

Of all, the hardest to read was Iris Chang’s work. I shut the book frequently so I could breathe between the pages. I learned about the devastating rape of girls and women and the sordid massacres of people in Nanking in 1937 as the Japanese army swept through the city during the Sino-Japanese war. The rape of Nanking was the prime reason why, five years later in Singapore, Japanese soldiers queued outside Cairnhill Road waiting to be served by women. Reasoning that they must prevent a recurrence of what happened in Nanking five years before, the Japanese military sexually enslaved hundreds of Korean—but also Chinese, Indonesian and Malay—women, offering what were called “comfort stations” scattered across Singapore. Most of these women suffered the patriarchy of these ruthless soldiers and returned home where, once again, they suffered the indifference of their families. Chastity being even more valuable than life itself, many women never returned home.

Every book I read in this season of binge-reading spoke of colossal loss—of the loss of agency, family and home. The theme of loss is heavy in Josephine Chia’s work, too, although she realizes that her government was well-intentioned in wanting to give Singaporeans a better life. In the epilogue to Goodbye My Kampong!, she laments the destruction of her village after it experienced another major flood in 1978. The bulldozers and cranes roared in right after. “They uprooted ancient trees unceremoniously, some of which we had climbed and loved. The attap houses were broken and crushed, years of history tumbling down and disintegrating. None of these things mattered to the laborers. They did not feel what we felt about the place. On the outside, it was just a shanty village of wooden houses and old-fashioned attap-thatched roofs. How could they know what the village had meant to us?”

Chia’s despair resonated with many people in Singapore for whom life outside their kampong would never truly hold meaning but the country was on a path to urban renewal and there were going to be many sacrifices along the way. Chia’s feelings about the loss of the kampong that had once meant so much to her made me reflect on my own memories of my maternal grandparents’ home (where I was delivered by a midwife) in India’s Kerala. It will be gone one day. The sharp scent of the thazhampoo flower, the room in the outhouse where once dhoti-clad men stirred vats of chakkavaratti even as the aroma of warm jackfruit sweetened the air. It will go, too. In its place a high-rise will be built.

It’s a humbling thought, that a record of my own history on this planet will only be complete when I no longer occupy a square-inch of it. I hope my children are reading. If and when they write the closing chapter of my life, they must not forget to mention that, above all, their mother loved the subject called history although she had dismissed it once in a moment of inexplicable imbecility.

You have created a thirst in me to find historical facts in my travels! Thx for the book suggestions too kal!

In most Indian towns, we have "sthala puraaNam", the lore of the place. Usually, tied to local Gods, Kings, and some odd peasant woman who challenged them. I loved learning about it, as a child whenever I went to a new place. While I love history, it invariably makes me sad, for two reasons: one is that inevitable death and decline. And, we are used to the humane, progressive conditions of the current day; any past history is full of blood and atrocities. The golden age is now (actually may be 1990s).

Thanks for the letter from across the oceans. Is there a "Sarum" like book that provides the view of Singapore throughout the history? Please let me know. Would love to read it.