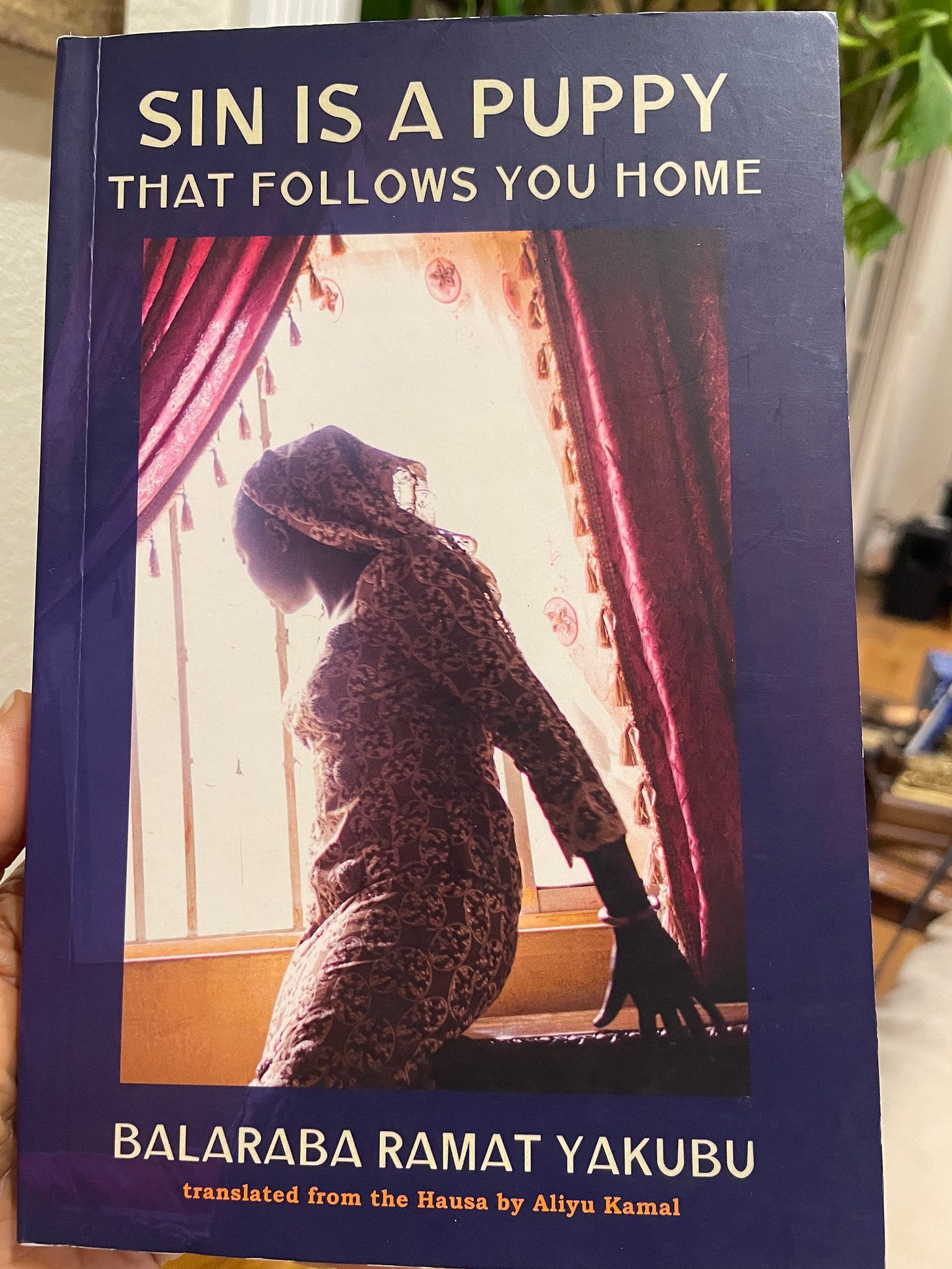

SIN IS A PUPPY THAT FOLLOWS YOU HOME

A story in the Hausa language ended up entertaining me while also infinitely exasperating me.

Until this week, I had no idea that there was a language called Hausa, a Chadic language spoken by the Hausa people in the northern parts of Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Benin and Togo, and the southern parts of Niger, and Chad, with some speakers in Ivory Coast and in Sudan as well. The novella I picked this week was written originally in Hausa and the book’s intriguing title is actually a popular saying among the Hausa people—SIN IS A PUPPY THAT FOLLOWS YOU HOME.

Authored by Balaraba Ramat Yakubu and translated by Aliyu Kamal, the novella was published, to my surprise, in my Indian hometown of Chennai by Blaft Publications in association with Tranquebar Press. Rakesh Khanna of Blaft says that all of the author’s nine novels have “boldly addressed hot-button issues of Hausa society, including forced child marriage and the right to education for girls,” issues with which the author herself was familiar since she herself was taken out of school and married by thirteen years of age.

One of the bestselling Hausa authors, Balaraba Ramat Yakubu published her first novel in 1987. She has also written, directed, and produced a number of films for “Kannywood,” the Hausa-language film industry based in Kano, Nigeria.

This novella is just about 125 pages in all, and it was absorbing enough that I bored through it in no time. Would I recommend it to others? I’m not sure. It’s a plot-based novel and hence it kept me turning the pages. Still, when I pick up a book to read for my weekly project, I hope that it will be an excellent story filled with many memorable elements of craft. While SIN IS A PUPPY THAT FOLLOWS YOU HOME didn’t satisfy me in that regard, I still could not put it down and that is saying something.

What kept me reading is also the patience that I’ve developed while watching Hindi and Tamil movies and television serials. This Nigerian book packs in all the metaphorical chutneys germane to Indian movies, rendering it a viscous experience that really won’t let you go even when you want to let it go.

We are told the story of Alhaji Abdu, a small-time business man, who is married to Rabi and is the father of nine children. Abdu not only neglects his family; he is a daily adulterer who ends up finally chasing Delu, a prostitute, until one day he marries her and brings her home. Soon, Abdu throws Rabi and her children out on the street without any financial support and continues to live with Delu. Rabi is tenacious, however, and continues to support her children on her own through her small food business, and she is helped by her sister Tasidi and brother Malam Shehu.

As it always happens in the Indian cinema of yore, there is an affluent man waiting in the wings for the young and beautiful Saudatu, Rabi's daughter. Alhaji Abubakar is that guy and he marries her and she becomes his third wife. The author doesn’t portray all the men in this story as misogynists. She has created a fairly nuanced portrait of family life.

For instance, the young Abubakar is the polar opposite of Saudatu’s father, and he tries hard to make his first two marriages work. He demands a divorce from his first two wives only when he sees no other way out of the mess. His love for Saudatu is real and she, in turn, is determined to make him happy and “obey” all his wishes.

The word “obey” surfaces all too often in the text and this unsettled me right from the beginning. Even the younger generation of women, Saudatu herself, for instance, decides that she must “obey” her husband. Her mother and her aunt tell her she must obey him. The women of this society rarely ever band together against the men, to denounce them categorically stating that they will not put up with oppression and ill-treatment. Most of the women are worried about self-preservation. The system is also rigged in favor of the male species, unfortunately, in the Islamic society as described in the novel. When a man can take up to three wives, as any man acquires another wife, the senior wives begin to brandish their entitlement and power.

Few husbands manage this power-play between their wives to their advantage and Alhaji Abubakar, too, is unable to do so effectively. On the other hand, he brings happiness and security into Saudatu’s family and they begin to respect his well-meaning intentions.

In the meanwhile, a few months into Saudatu’s marriage, Alhaji Abdu's business burns down and he loses everything including Delu who has been sleeping with just about every man in Kano. Many lessons are learned as Abdu’s sins haunt him day and night.

Abdu is humbled and asks for forgiveness from Rabi. In the end, even as Rabi recoils and tells the world she will not go back to her husband, society expects her to do otherwise. Her son in law Abubakar prevails upon her to forgive her husband. She does as he asks. Eventually the family is united again and they all live happily ever after. The patriarchal values in this community are so deeply entrenched that it’s hard to separate what is right for someone from what is expected of them in society.

What would have made this story more effective portrayal is if Rabi had, in the end, treated Abdu the way he trashed her. Instead, we arrive at an ending in which happiness is equated to Rabi and Abdu becoming “a couple” again. Sometimes the greatest happiness is derived from walking out of a toxic situation.

SIN IS A PUPPY THAT FOLLOWS YOU HOME is a treatise on how not to treat a woman; many of the men in this novella resort to slaps and kicks. Spousal abuse is par for the course in a marriage in the society depicted by Yakubu. The women in the story, vindictive and feisty as they are, are always overpowered by the physical strength of their men.

I was nauseated by the happy ending in the novella, of course, for life almost always never quite works out that way. More things go wrong than they go right; more often than not, people do find happiness even when the ending is not quite palatable to the family and to the society at large.

I groaned when Rabi actually went back to her nincompoop of a husband. Who knows what might happen when the dust settles and the man, once again, tires of his wife? As they say in Tamil, “you can never straighten a dog’s tail.”

Like you, I was dismayed and frustrated by the ending. This kind of thinking is so deeply ingrained and conditioned in so many societies and as long as people think that being married is the only acceptable state for a woman, nothing will change.

Blaft publishes some interesting stuff!