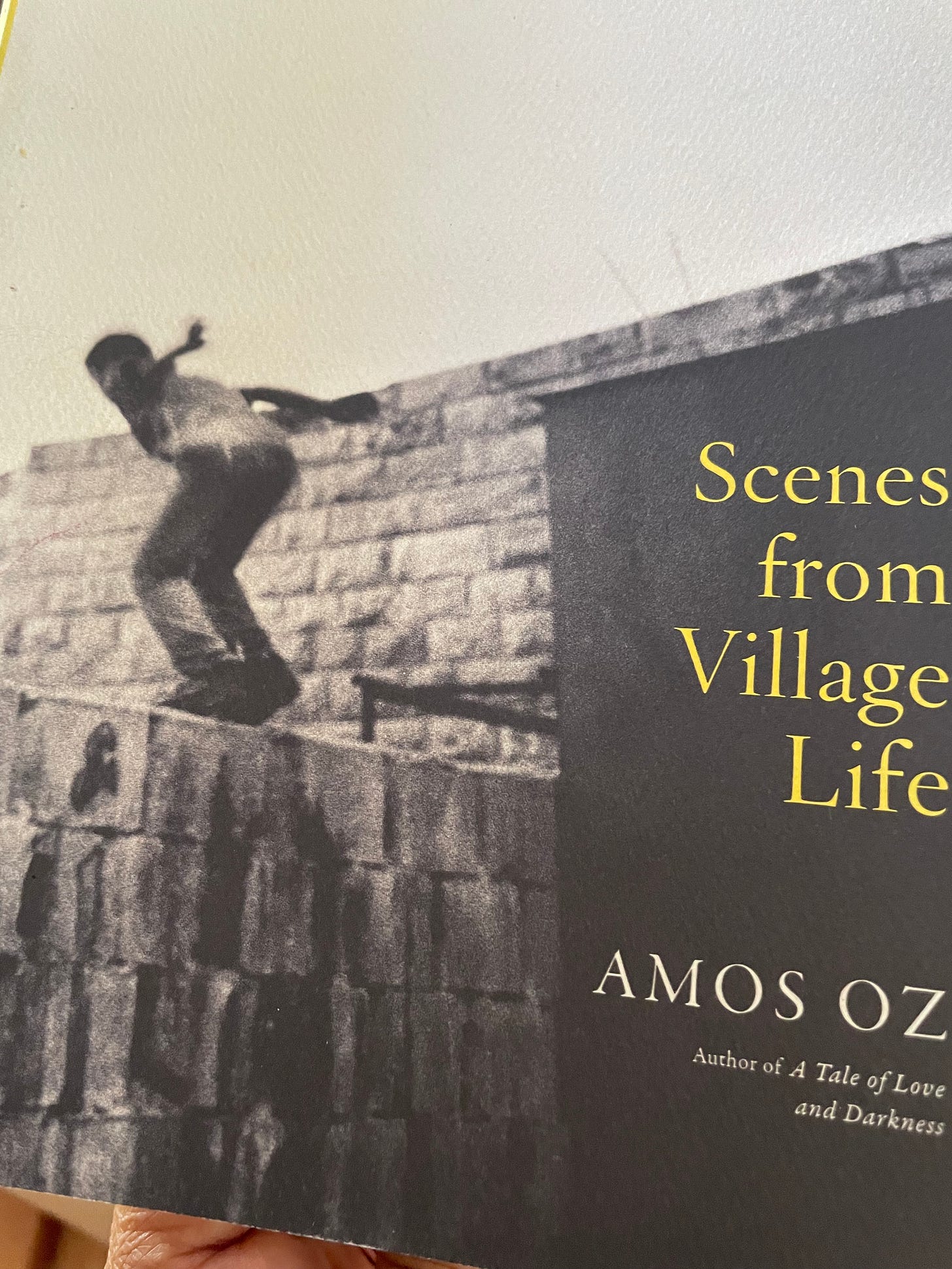

SCENES FROM LIFE

A Hebrew collection takes us into the heart of Israel but the characters could be from just about anywhere.

“And so the three of them lay, the woman whose house it was, her silent son and the stranger who kept stroking and kissing her while he murmured softly, “Everything is going to be all right, dear lady. It’s all going to be lovely. We’ll take care of everything.”

The story titled “Heirs” from Scenes From Village Life ends thus, with this scene of a contrived togetherness that left me incredulous, skeptical and moved. A stranger strolls into the home of Arieh Zelnik in the Israeli village of Tel Ilan and seems to know copious details about Zelnik’s illustrious family and its claims on the land. Something about him perturbs Zelnik and we realize by end of the story the extent of their similarities.

The writing captivated me from the beginning and, honestly, why won’t anyone read a story that opens so deftly—with this certain reaction—to the arrival of a stranger in one’s home?

“The stranger was not quite a stranger. Something in his appearance repelled and yet fascinated Arieh Zelnik from first glance, if it really was the first glance: he felt he remembered that face, the arms that came down nearly to the knees, but vaguely, as though from a lifetime ago.”

As we read on, we discover how Zelnik recognizes his own physical features in the other man who claims to be his long-lost cousin: The gait, the “simian” qualities, and the tendency to open every closed door.

The story brilliantly portrays how this pushy relative inches his way into Zelnik’s home and, quite literally, ends up sharing a bed with him and his mother. For Zelnik, who has lost his wife to another woman and has chosen to sever ties with his only son, this sudden appearance of an unknown relative fills a longing he cannot quite express. The comical ending took me by utter surprise, of course, but it was poignant and inevitable.

Heirs takes place in a village in Israel but I was startled by its relevance to my old life in India’s Chennai (formerly called Madras). When the morning train rolled into Madras Central, my parents never knew who the train might bring into our home. While it was expected that people would write us to inform us of their arrival, anything was par for the course during my childhood. Distant relatives happily rolled in, with bedding and trunks and we were expected to provide room and board for the duration without asking when they were leaving. This was the Indian modus operandi before families became nuclear. It still is, in the villages.

In the late 70s, a young man (my father’s cousin’s son) was at the gate of our Chennai bungalow early one morning. He left three years later. This young man, whom my mother resented at first, ultimately became a huge asset in our home. He helped my parents in various ways with chores both in and outside the house, and became the son my parents never had.

Another of the stories in this Oz collection, Relations, puts us inside the mind of an aunt, a doctor, who misses her now adult nephew. In his childhood, when he needed solace and reassurance, the boy found it in the home of his aunt. Much later, when he joins the army, he doesn’t seem to need her as much as she needs him. It’s heartbreaking to see the ways in which this doctor tries to ascribe reasons for not finding her nephew on the bus that should have brought him to her home. How many of us haven’t been there? I think of the number of times I look for messages from my children. I recall the number of times I swallow my pride and just place a call them because I cannot wait any longer. Oz’s stories are disturbing because they don’t often tie up loose ends. Things are just so. But how often do loose ends ever tie up in real life?

I found the ending of the story titled Singing incomprehensible and noticed that this seems to be a general observation about Oz’s story collection. Singing is set at a community sing-along at the home of Dalia and Avraham Levin. Every month, 30 friends from the village of Tel Ilan get together to sing to comfort one another and to huddle together even as the world outside is plunged in skirmishes. Their songs bring some amount of comfort to their hosts, whose son committed suicide four years before.

“They searched for him all over the village for a day and a half, not realizing that he was lying under his parents’ bed. Dalia and Avraham even slept in the bed without realizing that their son’s body was right underneath them.”

We see the Levins filling up the hours in the day to plug up the gaping holes in their lives, Little happens in this story but the misery is palpable. The singing overcompensates, it seems.

Another story, Digging, deals with the life of a 40-year-old Rachel, her irascible old father and an Arab boy, Adel, who lives in a shack on the property and does odd jobs in return for his shelter. It’s hard to feel any warmth for the old man.

He was a tall, vituperative man with a hunched back. On account of kyphosis, his head was thrust forward almost at a right angle. At eighty-six years of age, he was gnarled and sinewy, his skin reminded you of the bark of an olive tree, and his tempestuous temperament made him seem to be boiling over with strongly held ideals and opinions.

The old man and the Arab are spooked by a digging under the house. By the end of the story, in which nothing particular happens, even the daughter begins to suspect that someone’s digging beneath her bedroom. All three are suspicious of something chipping away at their foundation, a reference to the historical impasse between Israelis and Palestinians. Digging points to the generational skepticism, of a legacy of ill-feeling in the region.

Considered one of the most accomplished authors in the history of Israeli literature with 40 books including novels, short story collections, children's books, and essays, Amos Oz ardently supported the two-state solution.

In this 2011 interview for NPR, Oz observed that his stories in Scenes From Village Life were not so much about Israel as they are about the human condition. “It's about love and loss and loneliness and longing; it's about death and desire; it's about desolation and disillusionment.”