RESTLESSNESS IN NORWEGIAN

In this gripping novel, Nobel laureate Jon Fosse has plumbed the depths of that feeling we call restlessness to narrate a story of friendship and betrayal.

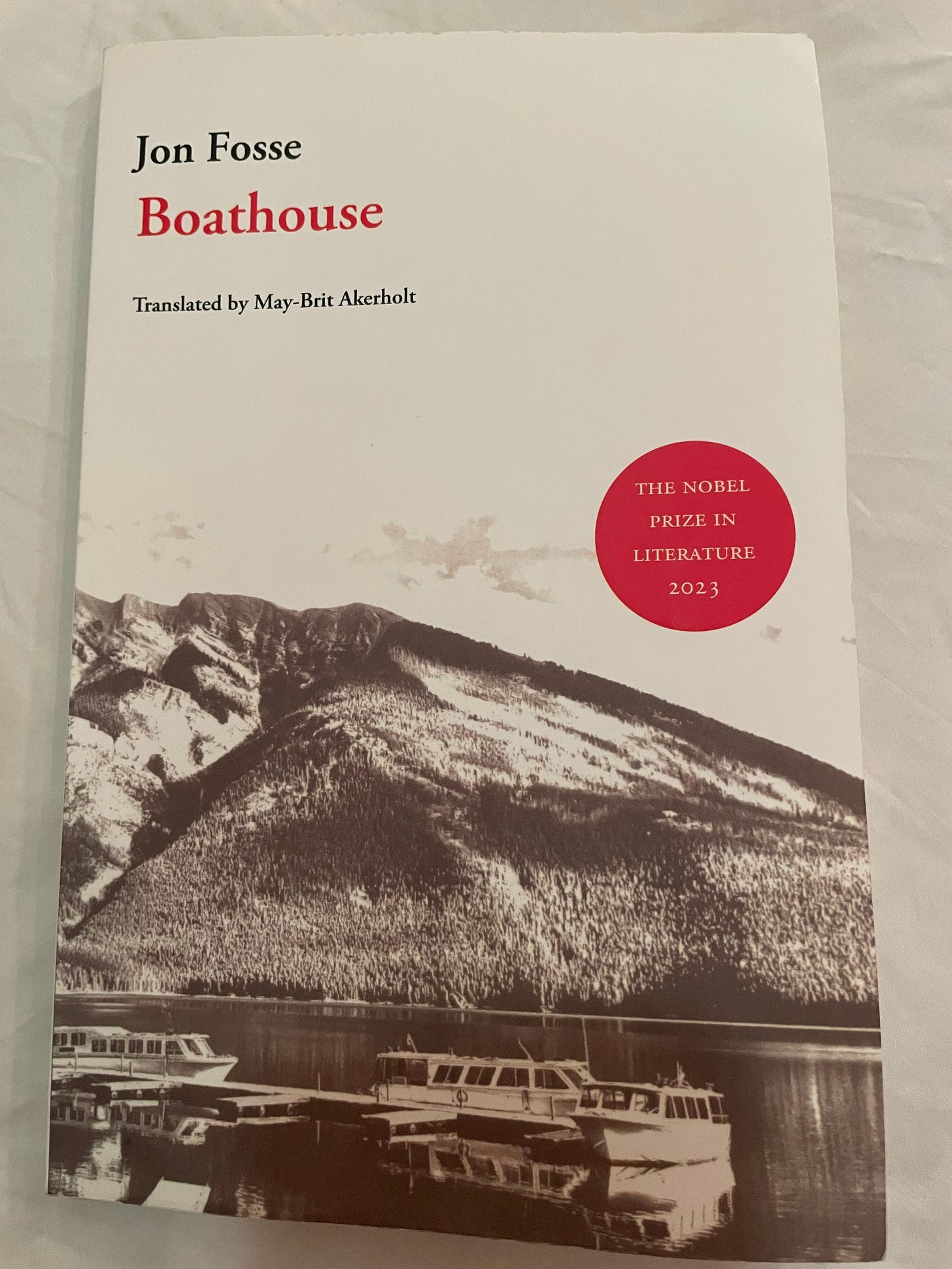

When Jon Fosse won the Nobel prize in literature last year, I made a mental note to read some of his seminal works. Boathouse is one of Fosse’s most acclaimed novels and it features an unnamed narrator who leads a quiet, lonely life with his mother until the day he unexpectedly encounters a long-lost childhood friend and his wife.

As the story opens, we learn that the narrator’s life is one in steady decline; he has lost his sense of self. He seems to have little motivation to even play the guitar, something he loved to do in his adolescence and during the years that followed.

I don’t go out anymore, a restlessness has come over me, and I don’t go out. It was this summer that the restlessness came over me. I met Knut again. I hadn’t seen him for at least ten years. Knut and I, we were always together. A restlessness has come over me.

The opening lines seemed to become a vice around my neck. The clamp tightened with every page. I read this entire work on a flight back to the United States from South Africa, and I thank Fosse for making my 15-hour journey implode into just a couple.

At 156 pages, Boathouse (translated from the Norwegian by May-Brit Akerholt) is a fast-paced read in which little happens. Yet everything that happens in the arc of a life flows through the pages, keeping us engaged, confused and disturbed: joy, excitement, first love, first kiss, friendship, desire, disillusionment, anguish, torment, envy, jealousy and betrayal. This work focuses almost entirely on the interior life of a man whose life has been shaped and given meaning and life by another being. It’s almost as if the narrator—whose name we’re told is Baard—has been living life as a parasite, living out his life according to the dreams and the desires of a friend called Knut who, on a day in their late teens, seems to just up and leave, for reasons we are yet to find out.

When we were kids Knut and I were always together. And Knut left. I called his name, but Knut just left. A restlessness has come over me. I looked at his back. I didn’t know what to say, I just saw Knut standing there, down on the road, and then he walked away down the road. I haven’t seen him since.

What makes Boathouse particularly memorable is this idea of the gargantuan impact of the life of one human being on that of another. What also reached out to me through the pages of this deeply disturbing novel is an aspect of family life that we often take for granted.

Early disappointments, disillusionments, and betrayals are part of the experience of one’s childhood and youth. They have a critical role to play, for they may even shape us into adults who grow up having developed a healthy dose of skepticism in our interactions. This novel asks questions about how we process all those early feelings of doubts about ourselves and how we internalize them in order to make ourselves more secure for the challenges in our future.

Clearly, every family is unhappy and dysfunctional in its own way, but there are some in which the lack of familial support and understanding can make a minor and momentary early disappointment in life metastasize into something momentous and much larger over the course of time. Baard’s life seems to be a classic case of family neglect and indifference. In his thirties, Baard still lives with his mother. The mother in the story is always on the floor below. He can hear her restless footsteps downstairs while he is writing upstairs.

Now I don’t go out anymore. We played this summer at the community dance, and since then I haven’t wanted to play with Torkjell any longer. I don’t go out anymore. My mother is walking across the floor down there in the living room. I hear the sound of hte television up here. A restlessness has come over me, my left arm aches, my fingers. My mother is not so old.

My interpretation of this is the lack of familial care and concertn, and the inability of the mother to reach her son, until, perhaps the end, when she walks up to his room to break some bad news to him. It’s the only time she seems to have shown any agency in her son’s life.

With the publication of Boathouse, Fosse was nominated for the Norwegian Critics Prize for Literature and received critical acclaim. Until I picked up this work, I had no idea that the Norwegian language had a written form called “Nynorsk” that was developed in the 19th century to create a language that was based on a mix of Norwegian dialects.

I’ve learned that Fosse’s works often end in tragedy. Boathouse is no exception, of course, and the end is somewhat abrupt and shocking. This novel is supposedly a star in the firmament of a celebrated body of work by Jon Fosse and hence I don’t dare to question why it was a landmark in Norwegian literature.

While Boathouse was a riveting read, it did not satisfy all my expectations in a novel of such preeminence. I understand that Fosse’s characteristic writing tends to follow a stream-of-consciousness style with endless repetitions and inner monologues, but I felt I was ejected from the work too many times. I had to read several sections all over again in order to make sense of it. Given the love the book has received, however, I must conclude that I’m missing an intellectual enzyme that allows me to appreciate this work wholeheartedly. The problem, I’m willing to concede, rests wholly within me. I close with the words of Jonathan Geltner who writes about Fosse’s work in his essay titled Jon Fosse’s Fiction. I have no doubt I will be reading other works by Fosse over the next many years.

Fosse’s chosen style in almost all his fiction is stream-of-consciousness, which means there is no narrator, no telling of a story, but rather the direct representation of consciousness. Such fiction is immersive, and the tendency after you get used to it is to go with the flow of primordial images and feelings, many of which are not there but are memories and visions of the past. But within those memories what we find is mostly keen sensitivity to the environment. It is a contemplative fiction powerfully evocative of scene and landscape:

~ Jonathan Geltner, Jon Fosse’s Fiction

Thank you for recommending! I’ve added it to my TBR list.