OF FAITH AND PLACE

I’ve noticed how faith is closely tied to one’s well-being in Singapore and how, for many locals, cross-cultural prayers are a part of daily life.

After I landed in Singapore, I realized that I’d forgotten to pack an idol of Ganesha and a brass lamp for my altar in my temporary home. A few weeks after I arrived, I bought a painted Ganesha barely more than two inches tall at Jothi Stores on Campbell Lane in Little India, the enclave dedicated to everything Indian. My diminutive altar is the symbolic center of my universe in our tiny serviced apartment when I light the lamp every evening.

At no time have I more keenly felt the power of a prayer as during Covid-19. Never have I been more convinced that there is an unknown hand—perhaps in a laboratory up in heaven—that dictates who gets to live and who gets to perish, and when. While I’m hardly knowledgeable about the ritualistic or the spiritual aspects of Hinduism, I think that belief in a supreme force keeps all human beings humble. In good and in bad times, faith brings meaning into our lives.

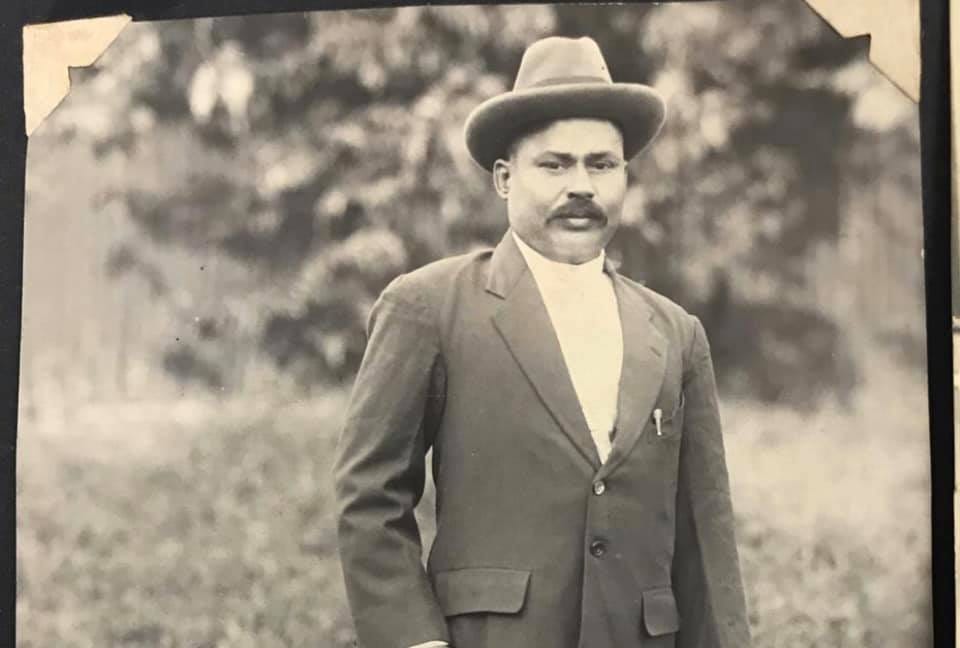

A third generation Singaporean, S. L. Mythili Devi, told me that her family’s implicit faith in the deity Mariamman, the female Hindu goddess known to vanquish illness and disease, had seen her grandfather, B. Govindasamy Chettiar, through many challenging decades after he sailed into Singapore harbor in 1906 as a boy of sixteen. Govindasamy Chettiar’s story was not different from those of many others who once lived in the hinterland of India’s Tamil Nadu and sought a fortune in distant parts of Southeast Asia. But few achieved his level of fame and fortune; fewer still turned around to help others succeed. By 1916, as the co-proprietor of a labor company at the harbor supplying wharf workers and stevedores, Mythili’s grandfather was managing over 3500 workers at Singapore’s harbor, then one of the busiest ports in the world. By the time of his death in 1948, his benevolence had earned him the moniker Kottai Govindasamy. Under the massive tented shed (“kottai”) at the port, he fed all who worked for him, and, really, anyone who went hungry.

In Singapore as in India, the story of temples and their beginnings often incorporated tales of people whose largesse contributed to the steady aggrandizement of temples and, consequently, of the communities involved in the building of such institutions. Thus the stories of Singapore’s many Hindu temples, I found, are also records of gritty people who were pioneering spirits in the nation. The first of them was Naraina Pillai who built the first Hindu temple in Singapore, Sri Mariamman Temple, in 1827, plowing his own funds into the temple in acknowledgment of his success. An entrepreneur in the brick business, Naraina Pillai was handpicked by Sir Stamford Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore, to oversee disputes of workers from India’s Coromandel Coast. First installed under a wood and attap roof, the deity still graces the main sanctum of the present day temple.

The Hindu-Buddhist religion and culture in Singapore can be traced back to the 7th century Srivijaya Empire, a thalassocratic empire in Sumatra (now Indonesia) which influenced much of Southeast Asia. It thrived until Islam’s expansion in the region around the 14th century. European imperialism altered its course forever. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, immigrants arrived in droves from South India to work as laborers in British Malaya and Singapore. With their arrival, we saw the building of shrines and temples in the towns, plantations and villages where they settled and worked. This was often the story of how temple towers, typically of South Indian Dravidian style of architecture, began to rise in Singapore in the 19th century. They have soared to a current total of approximately thirty temples out of which some have been declared heritage sites. While the Hindu Endowments Board (HEB) of Singapore manages the Sri Mariamman Temple, Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple, Sri Sivan Temple and Sri Vairavimada Kaliamman Temple, others continue to be privately managed, often by the continued sponsorship of families or temple societies in which members often share a common heritage back in India.

Mythili told me how the temple closely associated with her family, Sri Vadapathira Kaliyamman Temple, had been a source of great comfort in hard times. She recounted an incident in 1945 during World War II, when her mother was pregnant with her sister. The family, along with their grandfather, rushed into a bomb shelter (located across from the deity at Sri Mariamman Temple). For a time inside the shelter, her mother believed they had lost track of her husband, S. L. Perumal (SLP) and that his life would now be in danger. As her family waited inside the bomb shelter, awash in panic and tears, SLP walked in, much to everyone’s relief, reaffirming, once again, that their goddess, Mariamman, would always stand guard over their family. This deity had begun life under a banyan tree in 1830 in the form of a picture placed there by a female devotee. The location of the temple was unusual. It was evocative of another life-giving force, water; Thannir Kambam, or “water village” was a gathering spot, with several wells, at the intersection of Balestier Road, Race Course Road, and Serangoon Road, the last of which, one of the oldest roads in town, was an artery through Little India. Mythili says old cab drivers in Singapore often referred to this temple as “SLP Temple”. When Govindasamy Chettiar passed away in 1948, SLP inherited the responsibilities for the temple and shepherded it through an expansion that incorporated several deities and a grand exterior facade.

On one of our late evening walks through Serangoon Road, my husband and I stopped to watch the celebrations at this temple. I remember wondering, in general, about the temple’s many deities and their significance to Singaporean Indians. Mythili pointed out that for many people from specific parts of Tamil Nadu, their village deities guaranteed their safety. As they were often Hindus from the merchant and laborer classes from the villages in the south of India, they brought along their religious beliefs and practices, too, into Singapore and British Malaya. Periyachi Amman is one such village deity who is worshipped in hamlets around Thanjavur district in India’s Tamil Nadu. Periyachi is believed to guard expectant mothers. Not only does a pregnant woman perform a prayer at the end of the first trimester; on the 30th day after the birth of a child, a mother must place the baby at Periyachi’s feet to receive protection for a healthy and long life. Mythili pointed out that the communities also brought with them the cult of Draupadi, a Tamil folk goddess associated with the Hindu epic Mahabharata.

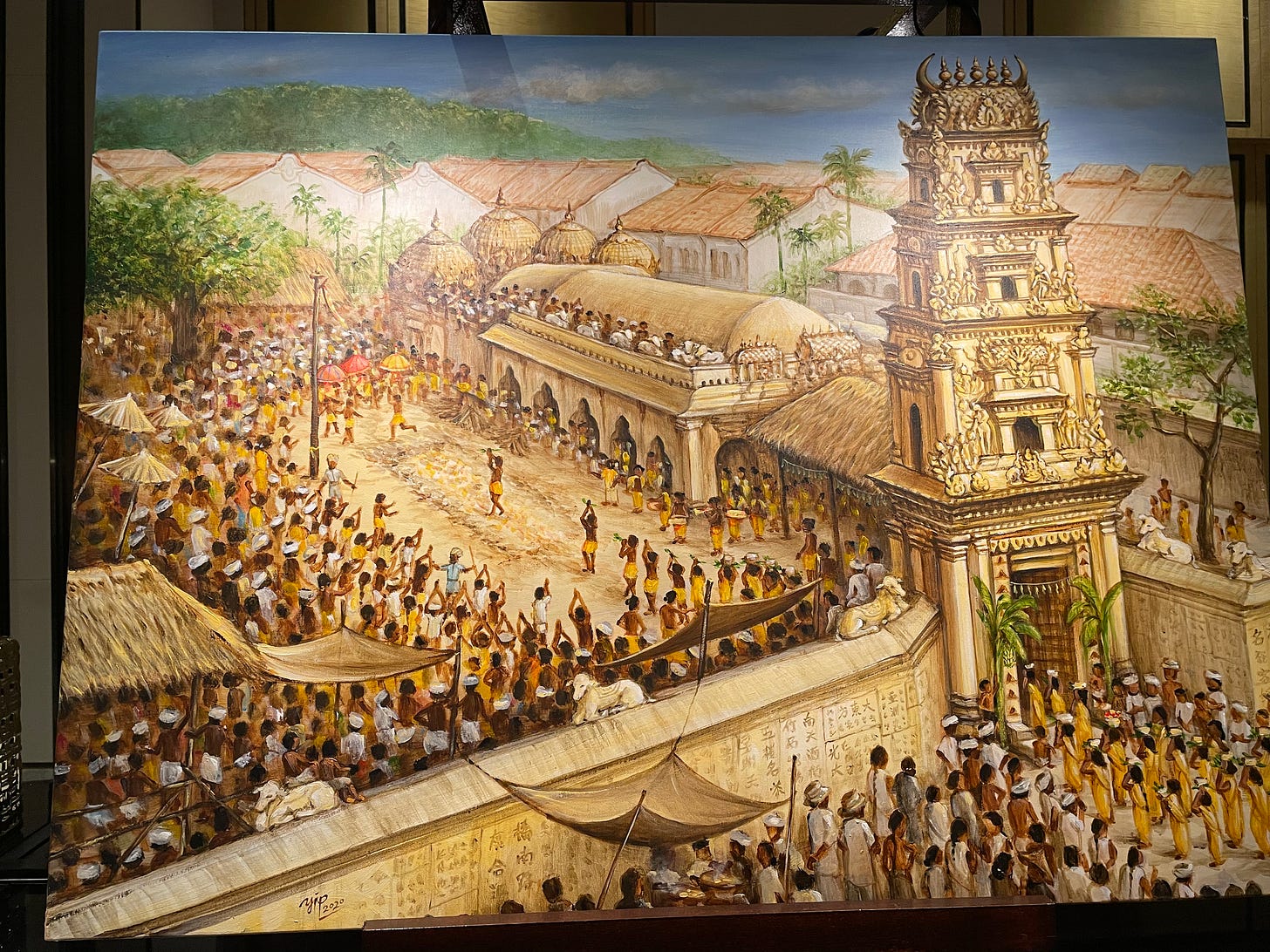

Inside Sri Mariamman Temple, the fire-walking ceremony, or Theemithi, has taken place annually since 1870. The physical act of starting the fire—managed by members of the boat caulkers’ community—was significant for all those boat builders who traced their roots to the coastal towns of Cuddalore and Poiganallur in Tamil Nadu. The grand finale of the story of The Mahabharata—when Draupadi walked on fire, in a ceremony known as Theemithi, to prove her virtuousness and chastity by her adherence to righteous living—is enacted yearly at this temple and hence the shrine to Draupadi is believed to be the second most important after that of Goddess Mariamman herself.

In mid-April I told my sister that my wish was to visit every Hindu temple in Singapore before I flew back to the United States. She suggested that I hire someone to take us around to several temples every Sunday for a few hours and that is what we did on a few Sunday mornings. We found ourselves walking into some of the most pristine spaces that Hindus had built, all immaculately maintained, of course, where it wasn’t clear what was more beautiful, the deity or the music of the nadhaswaram. The Singaporean government flies in topnotch artists to work at its Hindu temples and their quality has stunned me every time. In one temple, popularly called the “Ceylon” temple after the Sri Lankans who built the temple, the gentleman playing the nadhaswaram informed me he was from Yaazpaanam (another name for Jaffna in Sri Lanka), impressing me with his mastery over the instrument as well as the improvisational aspects of Carnatic music.

I included on our sightseeing list some Buddhist and Chinese temples as well. On our visits, I also began to realize how cross community worship was common in the country. At the Loyang Tua Pek Kong Temple built in the 1980s, visitors stop to pray at Buddhist, Hindu and Taoist deities, and a Muslim keramat (shrine)—all under one roof. The temple owes its existence to a group of friends, who, on finding figurines of different religions abandoned on a beach, decided to bring them under one umbrella in a unique approach that was in keeping with Singapore’s fundamental philosophy of multi-faith tolerance and religious harmony. Syncretic worship is a natural extension also of the evolution of Singapore: the worship of Hindu and Taoist deities is common, due in part to the polytheism of both faiths.

Faith assumes a different aspect altogether in this city. Places of worship are not merely gathering places for a specific community of people. Perhaps the history of the country’s old religious institutions that have survived bombings, internecine riots, and several administrative overhauls can narrate a story about the power of divine intervention? In Singapore, faith seems to be imbued with both a sense of history and divinity and the practice of religion is almost a way of life. A peek at a favorite god is like a stop for chai with a friend. It’s deeply personal. It has an everyday feel. At Wat Ananda Metyarama Thai Buddhist Temple, I saw people sending fervent prayers, joss sticks in hand—first, to the god of business and promotion, then to onward to the god of education, next to the god of good health and, finally, to the god of good luck. The gods here are many, depending on one’s state of mind. They seem to be listening, too.

Outside the Krishna temple on Waterloo Street, I saw both Singaporean Chinese and Singaporean Hindus praying at the old temple. In the time I was inside the temple several people, most likely returning from a work day, stopped outside on the road and lit joss sticks and prayed for a time before walking off to go about their business. This sort of casual, daily communing with a friendly god, even for ten seconds, puts things into perspective for all of us, reaffirming that we are mere bedbugs in the span of history. This 148-year-old Hindu institution—which sits next to the Kuan Im Thong Hood Cho Chinese temple—includes Kuan Yin, the Chinese Goddess of Mercy, in one its altars. (Kuan Yin is the Chinese name of Avalokiteshwara, who, in India, is believed to be the Buddhist counterpart of Lord Shiva.)

On our visits to Thian Hock Keng Temple, Singapore’s oldest temple on Telok Ayer Street, I sensed a powerful message from Mazu, the goddess of the seas. A rare space that embraces Taoism, Buddhism, Confucianism and ancestral worship, this temple used to face the ocean before land reclamation work began in the 1880s. It’s the first building that seafarers and immigrants saw when their boat reached the shores of Singapore. The sea passage in wooden boats from southern China was often perilous. New immigrants must have prayed to Mazu upon disembarking from their boats, hearts bursting with gratitude. I’ve no doubt that the return gaze of Mazu bore this truth: Every star up in the sky orbits not by accident but by a grand design that no one can even begin to comprehend.

so well researched! you've spent time in Singapore doing some good writing...

Superb, Kal. Well researched and written. Learnt a few things today-:)