NO COUNTRY FOR OTHER MEN

In this unputdownable French novel from a Rwandan native, we see how a nation can betray its people by allowing dysfunctional governments to pursue their horrific agenda.

It has been exactly 21 weeks since I began writing weekly about a book in translation. Thus far I’ve read 23 books. In one two week period, I burned through four volumes by Elena Ferrante in order to do justice to the Neapolitan series. Other than that unexpected departure from my reading habit, I’ve tried to be balanced, reading both fiction and nonfiction across a gamut of languages: Bengali, Greek, Polish, Hindi, Hebrew, Telugu, Japanese, Russian, Marathi, Spanish, Kannada and Malayalam.

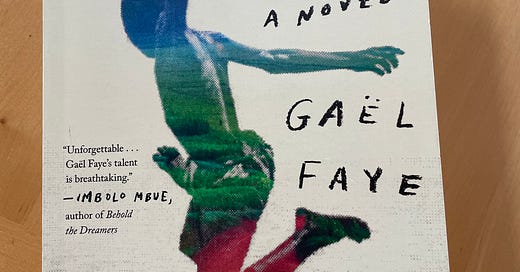

Last week I could not put out my weekly post because of travel and family reunions. In lieu of that, I did share some pictures of our two weeks out on the east coast. Even though I was carrying Gaël Faye’s Small Country on this hectic two-week trip, I began reading it only on the long flight back to the San Francisco Bay Area. Small Country was a traumatic read. While the novel demonstrated the human propensity for violence, reading After The Genocide, Philip Gourevitch’s 1995 report in The New Yorker, only reaffirmed the horror of it all.

Gaël Faye is a French writer of Rwandan origin—with a French father and a Rwandan mother—whose novel mirrors his own story of growing up in a comfortable expatriate neighborhood in Burundi’s Bujumbura, not far from neighboring Rwanda. The melancholy and despair of its opening pages did not prepare me for what was about to come. Small Country is a revelation about how a beautiful country can be altered by so much political unrest and mayhem that the people who once called it home will never be able to return and belong as they once did.

The book begins with a dramatic prologue that establishes the reason people fight—for no reason at all. It just is the way things are, writes Faye. The opening page has an exchange between the father and his son Gabriel, the narrator. Now this is a luminous exchange on the human condition. We hear 10-year-old Gabriel and his dad speak, with the son wondering why there is so much civil unrest in the nation he calls home.

“The war between Tutsis and Hutus…is it because they don’t have the same land?”

“No, they have the same country.”

“So…they don’t have the same language?”

“No, they speak the same language.”

“So, they don’t have the same God?”

“No, they have the same God.”

“So…why are they at war?”

“Because they don’t have the same nose.”

And that was the end of the discussion.

The 1994 Rwandan Genocide against the Tutsi was a power struggle between these two tribes called the Tutsis and the Hutus. Well before the genocide, the Hutus largely outnumbered the Tutsis, with “about 85% of Rwandans,” but over the decades the Tutsi people had been in power for a long time.

The two tribes had lived in relative peace for centuries and intermarriage between the tribes was also common. Outsiders first sensitized them to their inherent differences. Colonization drove a wedge between the people and showed them that they were innately different, one group being farmers, the other, herdsmen. In Rwanda’s story of internecine rift, I saw all the similarities to the blowback of colonization elsewhere in the world. In India, the British imperialists emphasized—and exploited—the differences between the Hindus and Muslims in order to strengthen their hold on India.

In 1959, the Hutus overthrew the Tutsi monarchy and civilians fled to neighboring countries. As it always happens, soon enough, a group of Tutsi exiles formed a rebel group known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). They stormed Rwanda in 1990 and fought until 1993 when both parties agreed upon a peace deal.

While peace remained elusive in Rwanda during the 80s while Gabriel was growing up, war did not exactly ambush him at his doorstep. What did seep into his home was another kind of conflict, that between his parents. Gabriel never quite understood what drove his parents farther and farther away from each other but one evening he was privy to their last evening together as man and wife. I was shaken by the visual potency of this scene, of nature’s pristine beauty against human misery, and I felt that it set the stage for the entire book.

“I felt hopeful that they would make up, that Papa would wrap his strong arms around her and she would lay her head on his shoulder as they strolled, hand in hand like lovers, through the banana plantation below. But it wasn’t long before I realized, from their angry gestures and jabbing fingers, that they were arguing. The banana trees swayed, a pod of pelicans flew over the headlands and the red sun plunged behind the high plateaus to the west as a blinding light covered the glistening surface of the lake.”

The lushness of the country pervades every page as the writer traces his life after his parents’ separation. The narrator is in love with his “land of a thousand hills”; Gabriel and his pre-teen friends make the most of their summer vacations. One afternoon, they’re out to steal mangoes from Madame Economopoulos’s yard and when she returns home in her small red Lada, Gabriel and his gang rushed over to her car to sell her “our mangoes”. Later they gorge on the remnants of their stash, their hands sticky and their nails black.

“Juice flowed down our chins, our arms, our clothes, and our feet. The slippery stones were sucked, sheared and shaved, while the underside of the skin was scraped and cleared out, then cleaned again. The stringy flesh clung between our teeth.”

From a moment that’s cloying with sweetness and nostalgia, the author drags us to the blood and gore of April 1994 when all hell breaks loose. The protagonist teen of the story grows up overnight.

The peace agreement between RPF and the Hutus broke on April 6, 1994, when a plane carrying President Juvenal Habyarimana, a known Hutu, was shot down. Hutu extremists blamed the RPF for the killing. In the hundred days that followed, all known people of Tutsi origin and any others who opposed the Tutsi killings were targeted for death—by bullet, grenade, or machete.

“Hutus in Rwanda had been massacring Tutsis on and off since the waning days of Belgian colonial rule, in the late fifties. These state-sanctioned killings were generally referred to as “work,” or “clearing the bush.”

After The Genocide, Philip Gourevitch’s 1995 report in The New Yorker

The mass genocide—the killing of over 800,000 people—happened most often by the blade of a machete inside residences, refugee camps, churches and schools. Government troops backed up the Hutus, many of whom forced civilians and youths to fight and to exercise the slaughters. France actively supported the Hutu-led government of Habyarimana against the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front, launching “a vast humanitarian operation called “Turquoise” to put a stop to the genocide and secure part of the country.”

As Gabriel observes, however, “Maman said it was a final dirty trick by France, which was coming to the aid of its Hutu allies.” In the end, neutrality is simply impossible, we learn. And as The New Yorker’s Gourevitch makes clear in his deeply reported story, it’s one thing to apprehend one person (and his operators) for masterminding a pogrom, as it was in the case of Hitler’s Germany during the second world war, but it’s quite another to book hundreds of thousands of assassins who had been indoctrinated by a propaganda machine that remains elusive, nameless and faceless.

“In other words, a true genocide and true justice are incompatible. Rwanda’s new leaders see their way around this problem by describing the genocide as a crime committed by masterminds and slave bodies. Neither party can be regarded as innocent, but if the crime is political, and if justice is to serve the political good, then the punishment has to draw a line that would sever the criminal minds from the criminal bodies.”

Faye’s work ends on a hopeful note, of course, but the book is laden with so much angst that it weighed me down. Even though Gabriel never bore the marks of the machete—unlike many other Tutsis who lived to tell the tale—the scars, visible or invisible, are there in every Tutsi heart. At the end of the book, it’s also clear that the pain of the Tutsi reverberates in the heart of the Tutu. It really doesn’t matter who killed whom. This cannot have been. It must not be. It was wrong. It was unnecessary.

Rwanda today is a peaceful nation and has been politically stable since the 1994 genocide. With universal health care for its thirteen million people, this diminutive landlocked nation in Africa has become a success story for the rest of the continent.

Small Country was an affirmation for me, personally, about the value of this weekly project; we read in order to learn about others for there’s seldom a time when another life does not inform our own. As I said earlier, Gabriel’s story resembles the writer’s own story but as Faye makes it clear in this interview by Jaya Bhattacharji Rose, Small Country is a work of fiction.

The last chapter of the book drips with the pain of loss—of lives, of memories, of the sounds of future generations. Faye recalls a poem by the late Jacques Roumain, a celebrated Haitian poet. In his words I felt the tug of the cord that connects me to the land of my birth.

“If you come from a country, if you are born there, as what might be called a native by birthright, well then, that country is in your eyes, your skin, your hands, together with the thick hair of its trees, the flesh of its soil, the bones of its stones, the blood of its rivers, its sky, its flavor, its men and women…”

Well written Kalpana.👍 Having stayed there for two decades couldn't resist from writing about that country .

Rwanda though small in its land size, is rich in scenic beauty. Tourists from western countries throng Rwanda to see the mighty mountain Gorillas. Resilience with which she has grown over the years and stands tall today is story unparalleled. Security in Rwanda is one of its best in the whole Region. It is the first country to ban single use plastics in the Region. Rwanda is also known for its excellent cleanliness and orderliness . Rwanda Successfully concluded the prestigious CHOGM (Commonwealth Head of Government Meeting) with participation from as many as 54 commonwealth nations in June 22. No wonder the country is becoming a leading tourist and technical hub.