METICULOUSNESS AS A WAY OF LIFE

If a country expects and practices meticulous follow-through, why won’t its people do the same?

“I would have given you guys a hundred on hundred for this display,” I said, “but for the fact that you didn’t show Little India clearly enough.” The docent laughed and looked towards where I pointed.

At the time I was taking in a 3D miniature model of a mini fragment of Singapore city at the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) gallery. The neighborhood of Little India or “Serangoon” was shown as a nondescript area with rows of trees and random towers. But Serangoon was Singapore’s liveliest, scruffiest enclave with Indian grocery stores, pawn shops, temples, restaurants and street-length markets peddling everything from lotuses and banana stems to cheap fabric and watches. I felt that in the 3D model, the uniqueness of the precinct was nowhere to be seen.

“Look,” the docent countered, “we’ve shown the Indian Heritage Center right here.” She pointed to a blocky brown building whose facade was a spitting image of the real edifice. I told her that didn’t cut it.

“Just one gopuram, a temple tower, right here, would have conveyed the location to me, see?” As we stared at it, she realized, right away, that just a few feet yonder, a mosque had been indicated with a golden dome, probably Masjid Angullia which was just a five-minute walk from the landmark Srinivasa Perumal temple. A little detail, I said, that would make all the difference for a visitor.

My constructive criticism—peevish and unwarranted, my late father may have said—stemmed from the attention to detail I’d observed throughout the URA gallery. Here was one of the manifestations of a country’s systemic need to do things with both head and heart and with an unflagging meticulousness.

The URA was unlike anything I’d seen before. Its mission and motto on its website—“To make Singapore a great city to live, work and play”—do not capture its multifarious roles. It is Singapore’s land use planning and conservation authority. It manages the development of the city’s strategic long-term plans. It guides its physical development in a sustainable way. It is also the force behind the conservation of temples, shophouses, bungalows, and other renowned institutions built during colonial times.

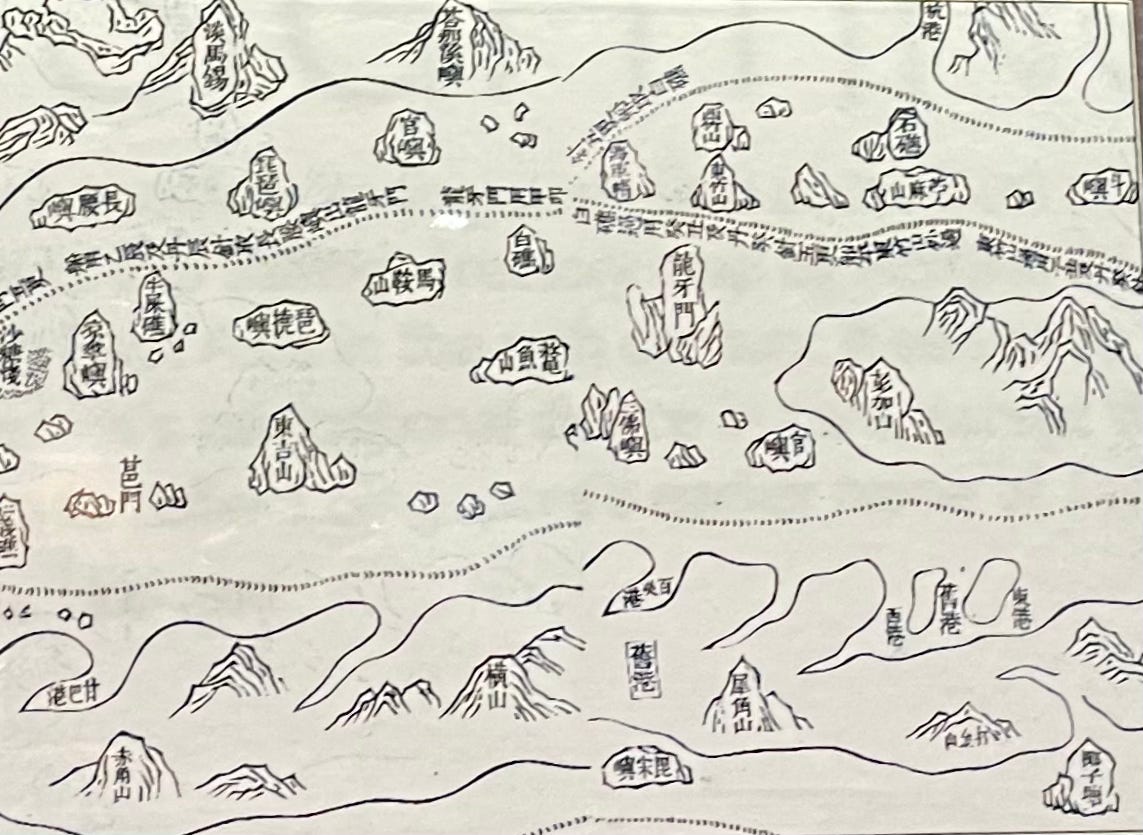

To be inside the URA is to be mesmerized by maps over the centuries. The curation leads us, quite masterfully, through the progression of 600 years in the life of an island nation. Through these maps—which merge historical, geographical and political shifts—we also begin to see a small country’s explosive growth, literally, owing to land reclamation. A map from 1898 shows the 24 km railway line pushing goods from Tanjong Pagar by the port of Singapore all the way to Johor on the tip of Malaya. We also see how seven pebble-like islands in the southwest of Singapore were mashed together through land reclamation to make one larger island called Jurong to create a shipyard to handle many times the current traffic. URA tells both locals and visitors how this nation planned its growth and the preservation of its culture and heritage.

How must a city or a country use its land? How must it apportion it so that all the people do not tend to flock to one part of it to live work and play? How do we keep the traffic flowing freely? What may be the best way to ease the mobility of both people and goods? How do we value what is central to our tradition and prop it against present-day desire for all the trappings of modern life? How do we make old heritage places reusable as modern spaces? This gallery describes how over fifty years ago Singapore chiseled out a workable plan to address questions such as these.

The questions URA grapples with apply to every city we may live in. An architect, Reena Rao, a longtime Singaporean, told me how in Singapore the approach to everything is holistic. Everyone involved in any project is deeply committed. She told me it was quite simple. People in Singapore go off and execute on a vision that has been thoughtfully articulated by a group of people. Mostly, though, they just shut up and do the work. This is one of the hardest things to do and do well.

A recent story in The Strait Times reiterated Singapore’s tendency to both do the work and measure itself on the work that has been done. In October 2020, a glitch in the MRT system (subway) resulted in 6,700 commuters being stranded in trains. A rusted component had led to the disruption of services for three hours. Six months after the incident, the paper disclosed the results of the investigation, along with details of how the parts had been fixed. There were several other articles as well. One of them detailed how the country was investing in a three-track train testing center—one of the first of its kind in the world and to be ready in 2024—in order to test trains without disrupting regular passenger services.

The push to improve existing public services is constant. It seemed to translate to measurable performances for individuals, too. I’ve watched bus drivers carry out their duties whenever someone in a wheelchair waited at a bus stop. In all the instances, the driver got up and walked over to the middle of the bus, tugged at a handle inside an indentation in the floor and eased out the ramp. Passengers waited by the entrance patiently—boarding the bus was always up in front so that the driver ensured that they paid their fares—because the special needs person received help first. When passengers offered to help with the wheelchair, they were shooed away by the driver. Here, once again, was an orchestration of events that had been thought out in such detail that most human errors were averted from the outset.

Another public service in the city frequently catches my attention because of the number of reminders I receive from it. When I borrow books from the National Library Board, I’m informed about the books I’ve got on loan and the day my books will be due. Closer to the date, the reminders arrive every 24 hours. The country has figured that instead of relying on humans to do the right thing, it will just prevent problems as often as it possibly can at no great cost. When I return books, I receive a notification about which ones I returned.

I also receive advice from library personnel that immediate automatic renewal protects people from fines. In the United States, that is always the responsibility of the borrower. Here in Singapore, the system warns, suggests, reiterates, advises and protects—so often and with such a pleasant and passive aggression—that the borrower just does it as a matter of routine precaution.

Singapore doesn’t even give its citizens an opportunity to make a mistake, thus underscoring its meticulous approach in every aspect of public life. It’s another way of saying: “We’re there to protect you—from your own failings.”

Doing something by the book is ever a feature of daily life in Singapore—whether it’s contact tracing, walking up to the thermometer, or staying rigidly focused on the letter of the law. It reminds me of something my daughter said to me on and off, that as an older teen she would hear my voice in her head cautioning her to stay within the lines of safety and propriety.

In Singapore, I always hear a voice in my head warning me to not jaywalk or miss an appointment or skip paying my bus fare. Strangely enough, just while I was mulling over this country’s attitudes something happened to reinforce my beliefs. A few minutes after I’d sat down in the bus yesterday, its driver sought me out and told me to tap my bus card once again just to make sure that my card had been debited. We discovered that the card had worked the first time around, after all.

The driver, now all contrite, apologized right away: “Sorry ah! For some reason I thought it didn’t work lah!” I laughed it off. “No problem, sir, you are just doing your job,” I said, even though I was mildly annoyed that he had asked me to walk up to the machine and check my card against the system.