Do not drink when you’re reading Etgar Keret. You’ll find yourself laughing out loud or crying. Either way, it’ll serve you well to keep a box of tissues handy. Keret, who is fluent in English, writes in Hebrew. Aside from several wondrous national awards in Israel, he has also won the Chevalier (Knight) Medallion of France's Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. If you’re on Substack, you can read him at Alphabet Soup.

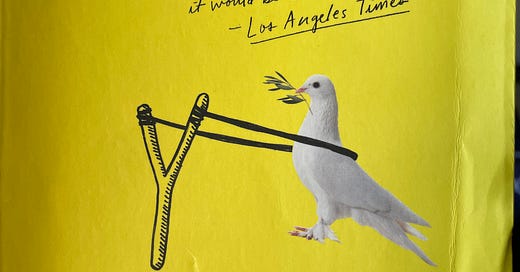

The Seven Good Years: A Memoir features 36 short essays with a whacky, serrated edge translated by Sondra Silverston, Miriam Shlesinger, Jessica Cohen and Anthony Berris. It is a journey through seven years, starting with the birth of his son until the passing of his father.

The book begins with the day Keret’s wife, Shira, goes into labor. Her water breaks in the taxi driven by a neat-freak taxi driver who is afraid “it would ruin his upholstery”. The hospital to which they are headed is caught up in the chaos around the victims of a recent terrorist attack. Keret’s excitement at becoming a father is deflated by the attack that’s likely slowing down his wife’s contractions too: “Probably even the baby feels this whole getting-born thing isn’t that urgent anymore.”

Keret is so funny that I was left wondering if he could be funnier still in Hebrew. I’m unsure if I can convey this to readers who have been birthed and raised in an English-only world. I think English traded piquancy for privilege. English doesn’t have foam. It can be tepid. Imagine a Starbucks latte that has been taken home and left on the counter for seven hours before being zapped in the microwave. It may be time to feed the vapid liquid to your sink or your cactus.

I can never carry a brilliant adage from my mother tongue, Tamil—conveying the horror, the sarcasm, the eye-roll, the vitriol, or whatever—into the English language with the same “tang” with which it was uttered. A language, like a speaker, has “mood” depending on the moment. How do we ever deliver that in English?

I recall something that Spanish writer Isabel Allende said in a discussion with Don George at Book Passage in Corte Madera in 2000, just as I was starting out as a writer. When asked why she didn’t write in English when she was so totally fluent in the language, Allende didn’t miss a beat and retorted with a question of her own. “How do you make love in English?” she asked as the audience imploded into spasms of merriment.

Reading Keret made me ponder Allende’s observation. It’s not to say that I didn’t laugh out loud while reading Keret in English. I was left wondering about all the inexpressible details that had to have been sacrificed at the altar of translation. Thankfully, Keret is a skilled screenwriter, too, and hence his innate gift for storytelling in scenes seems to have translated really well into English.

As a Jewish man in the land that has been in turmoil for the last century, Keret’s stance on simply being alive is both hilarious and distressing. “As a stressed-out Jew who considers his momentary survival to be exceptional and not the least bit trivial, and whose daily Google alerts are confined to the narrow territory between “Iranian nuclear development” and “jews+genocide”, there is nothing more enjoyable than a few tranquil hours spent discussing sterilizing bottles with organic soap and the red-pink rashes on a baby’s bottom.”

In his essay titled Throwdown At The Playground, he presents the moment a young mother in a park asks him if his son—whose rear is currently buttressed by diapers—will enter the army. All of Keret’s angst over military service while pondering the futility of war is penned in delightful, laugh-out-loud vignettes in which an army of diapered babies thunders down the hillside.

As we move through his works one little essay at a time, we find out about his sister who, we are told, is no more. She is not dead, however. People can die when they change and become unrecognizable to another. Keret repeats the line about her death throughout this essay and drives home his hurt over and over again in one of the most poignant essays in his collection.

I was thinking of its relevance now, at a time when the whole world is converging on a war that, literally, no one wants. War cries ultimately echo in the home, as we know all too well, and Keret’s words made me wonder about all those intimate relationships that can blow up in our faces as we grow older. A whole Red Sea begins to flow between Etgar Keret and his sister as she navigates adulthood and in his essay titled My Lamented Sister, he reckons with how nothing will bring the siblings closer physically or emotionally. As far as Keret is concerned, his sister is dead because he doesn’t know her anymore.

She has become so cemented to her religious beliefs that she cannot accept her brother’s values anymore. When Keret visits her, he’s given a “strictly kosher glass of cola” while the sister sits on the other side of the living room. Keret lays out the dual realities of their existence in a brilliant paragraph. “She loves it when I tell her that I’m doing well and I’m happy but since the world I live in is to her one of frivolities she isn’t really interested in the details. The fact that my sister will never read a single story of mine upsets me, I admit, but the fact that I don’t observe the Sabbath or keep kosher upsets her even more.”

My heart cracked many times while reading the essay. I thought about all the values my late father held that I pooh-poohed as I became an adult. I reflected on the beliefs my husband and I carried into our lives in America that our children now defy and question to this day. Keeping a relationship intact from birth until death requires diplomacy, compromise, tolerance, a sense of purpose and, above all, a deep, abiding love that must sometimes transcend logic.

It isn’t until we arrive at an essay close to the end of the book—in which the author reminisces about his father’s death—that the stark reality of all sibling relationships hits us. Keret, his brother and his sister are with their mother for shiva, the week-long mourning period in Judaism for first-degree relatives. Keret informs us that his parents left their three bedrooms “exactly as they had been, as if they knew we’d come back one day”; on the last day the three siblings try to steal another few minutes alone together before they exile themselves into the permanence of their dissonant lives.

“My sister will go back to the ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem neighborhood of Mea Shearim and my brother will fly back to Thailand, but until then we can still have a cup of tea together, eat the strictly kosher cookies I brought for my sister from a special store, savor the stories we heard about our father during the week of mourning, and be proud of our dad without apology or criticism, just like children should.”

Life must go on as if nothing has happened, as he writes in Pastrami, his final story of the collection. He describes how he and his wife lie out on the road one day, one on top of the other, with their child in between, as air-raid sirens blare around them.

***

That was such a lovely read! So much food for thought. And my to-read list just got longer :).

One thing Keret and you have in common is story-telling. The point that was driven to the reader is settle all scores with family and friends as life is too short. All of life events, emotions, and people is impermanent. Beautifully written piece.