INSIDE THE BAOBAB TREE

In this artful journey in the Afrikaans language, Wilma Stockenström, a descendant of the Afrikaner people, writes about a slave girl's life. Here is a work of art.

“Wearily, I take the path to the river, there in the cool to fill my being with the sounds of my sister-being, to refresh myself in the modest scents of pigeonwood and mitzeerie, to let my gaze end in a tangle of monkey ropes and fern arches and the slowly descending leaves, and to find rest, all day long, all night long.”

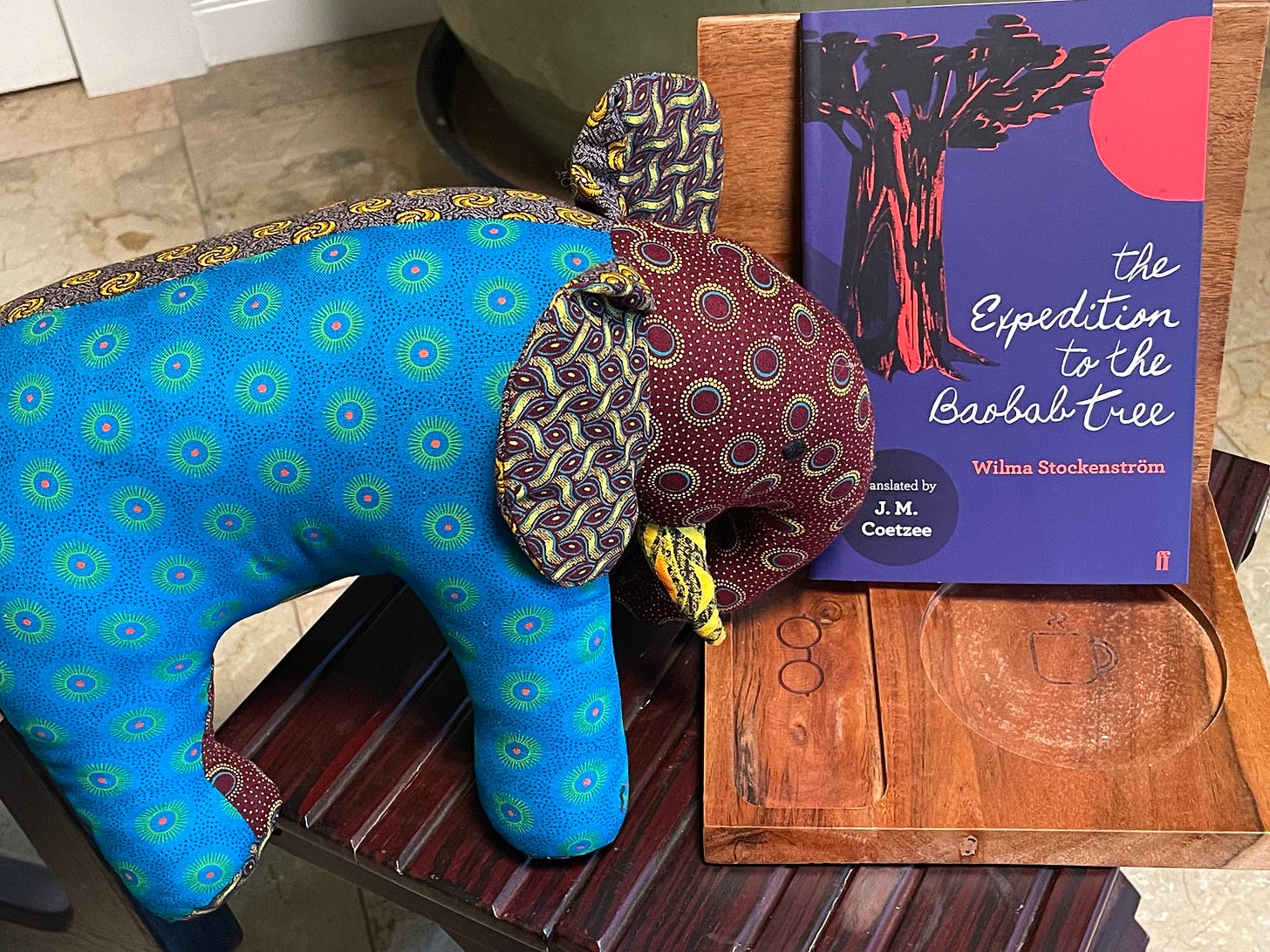

I was hooked to the idea of this book weeks before I ran into it inside a historic bookstore in Cape Town in September. What had already intrigued me was the name of the book’s translator, the renowned South African writer J. M. Coetzee, who won the Nobel prize for literature in the year 2003 for, quoting The Guardian, “dark meditations on post-apartheid South Africa that have been acclaimed for reflecting the human condition.”

Originally conceived in the Afrikaans language, The Expedition to the Baobab Tree by Wilma Stockenström is a deeply moving and lyrical account about the eternal human quest for personal freedom. The protagonist is an unnamed slave who has been sold into slavery many times over. When we first meet the woman, she is inside the hollow of a baobab tree and she knows the interior of the tree “as a blind man knows his home.”

I know its flat surfaces and grooves and swellings and edges, its smell, its darknesses, its great crack of light as I never knew the huts and rooms where I was ordered to sleep, as I can only know something that is mine and mine only, my dwelling place into which no one ever penetrates. I can say: this is mine. I can say: this is I. These are my footprints. These are the ashes of my fireplace. These are my grinding stones. These are my beads. My sherds.

We watch her life in the hollow and worry for her safety as she tells us about life in the open grassland in South Africa. We learn she’s alone and realize soon enough that she copes admirably well for someone who is the only survivor of a thwarted expedition to discover a new city. By and by, we learn the story of her life and that of the progress of the expedition until the day we find her inside the baobab tree.

The veld comes alive on the page and the work entices us to read every sentence many times over. What makes this exercise in lyricism so immensely readable, however, is its pacing and its structure.

My path to the stream, made by me who tread so lightly, thin, faintly winding, weaving past bush and tree trunk and through flat grass plains where the winter is beginning to lie red—my path runs down a final sudden slope to sun-irradiated water wide as my outstretched arms between the trunks of two young matumi trees guarding my drinking place. Further downstream I wash. Higher up, where this tributary debouches into the main stream, is the elephant’s ford.

Stockenström lets us gambol about in the veld with the elephants, the monkeys and the steenbok deer and, all of a sudden, we’re yanked back into the past life in a coastal town where the slave girl has no agency even when she’s her master’s favorite possession. This sway of the narrative from the past into the present and back into the past keeps us reading—with our entrails knotted in tension. What we discover is that even when a woman has no agency she may summon up her will, grace and courage to hold her own against the wrath of the world.

I became a shell plucked form the rocks but kept my oyster shell of will, my thin deposit of pride, kept myself as I had been taught. I did not give in. I did not surrender. I let it happen. I could wait. I listened to the beat of the waves far behind his groaning, and it lulled me. I was of water. I was a flowing into all kinds of forms. I could preserve his seed and bring it to fruition from the sap of my body. I could kneel in waves of contractions with my face near to the earth to which water is married, and push the fruit out of myself and give my dripping breasts to one suckling child after another. My eyes smiled. My mouth was still.

The Expedition to the Baobab Tree leads us into alien worlds. We watch a slave procession through the coastal town, the slave hunter rocking on the shoulders of his captives, while he is followed by “those in chains, some with packs of leopard skins, elephant tusks, rhinoceros horns and provisions on their heads, their faces twisted as the neck irons chafed them, followed by the young women and tender little girls shackled to each other with lighter chains.” At the square near the sea, we watch how slave traders pick and prod at the body of the potential “object” for sale, examining the head, counting the teeth, touching the pelvis, the arms and the legs. In the vast bush we see carcasses of animals and little and big people, and shrink in disgust at the stench of putrefying flesh.

Without question, if the veld is unforgiving and mean, the world of human beings is even more ghastly. When her owner dies in her arms in the house by the sea, the slave girl’s life careens into uncertainty yet again. She is bequeathed to the kind younger son of her owner.

One day, to her misfortune, her young owner dies in a drowning mishap. Twisted with grief, she is determined to take ownership of her life. She goes in search of a “Stranger” who is a frequent visitor to her master’s house and tells him that she wants to be with him. Now she chooses to be another man’s possession; for the very first time, it’s of her volition. Where he goes, she goes, too. When he chooses to go on an adventure to discover a city far away, she must go, too. Thus the woman is in constant movement, in an endless search of a final resting place. During this quest, she asks questions about all that she has lost—children she has borne that were snatched away to be sold at the slave market.

Where were the children I had brought into life? How would I be able to recognize them if I bumped into them somewhere? And would I be able to recognize them? Sometimes I looked attentively at young faces, searched for myself in their features, their voices, their behavior, their posture—assuming that my children were all here, I thought bitterly, and not sold into service in other cities and countries.

The end of this haunting work is a natural and fitting progression of the story, and so evocative of the land to which the woman is linked in both mind and spirit. She is free. Her thoughts and her actions are now hers and hers alone.

When I go to a new country, I always visit bookstores to get an idea of what locals are reading. Invariably, the person running the store has a lot to say about the place, too, and I end up visiting something because of a tip I received at the shop. At Cape Town’s The Book Lounge, for instance, its owner pointed me to several respected authors from all over Africa.

Almost every author in South Africa (and in many parts of Africa) now writes only in English or French (or the language of the colonizer). South Africa is home to eleven official languages: Zulu, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Tswana, Venda, Ndebele, Tsonga, Swati, English, among others. Despite this, as the owner of The Book Lounge told me, to publish in a language other than English in South Africa automatically affects the reach. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o puts it so eloquently in this interview, Africa is telling its stories in a European language and this needs to change.

The bookstore that left me in raptures was Clarke’s Bookshop on Long Street where I found The Expedition to the Baobab Tree and a handful of other books in translation from Zulu. In this beautiful historic space that was once a home, I saw photographs, maps and volumes of old books on South Africa so lovingly preserved.

What’s heartbreaking about my pick this week is that the tale of this slave girl is the story of so many others torn from their home and hearth to be carted onto boats to faraway lands. Is it any wonder that four centuries after 1619—when the first boat with a cartel of slaves landed in America’s Point Comfort—the cries of outrage still continue to be heard in this country?

“In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the English colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists.” ~~~The 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah-Jones.