IN THE SUITCASE TO SOUTH AFRICA

What might we bring with us on our journey to anywhere if all we were given was a suitcase to fill up? If every object in the suitcase had to tell a tale about you and our world, how would you choose?

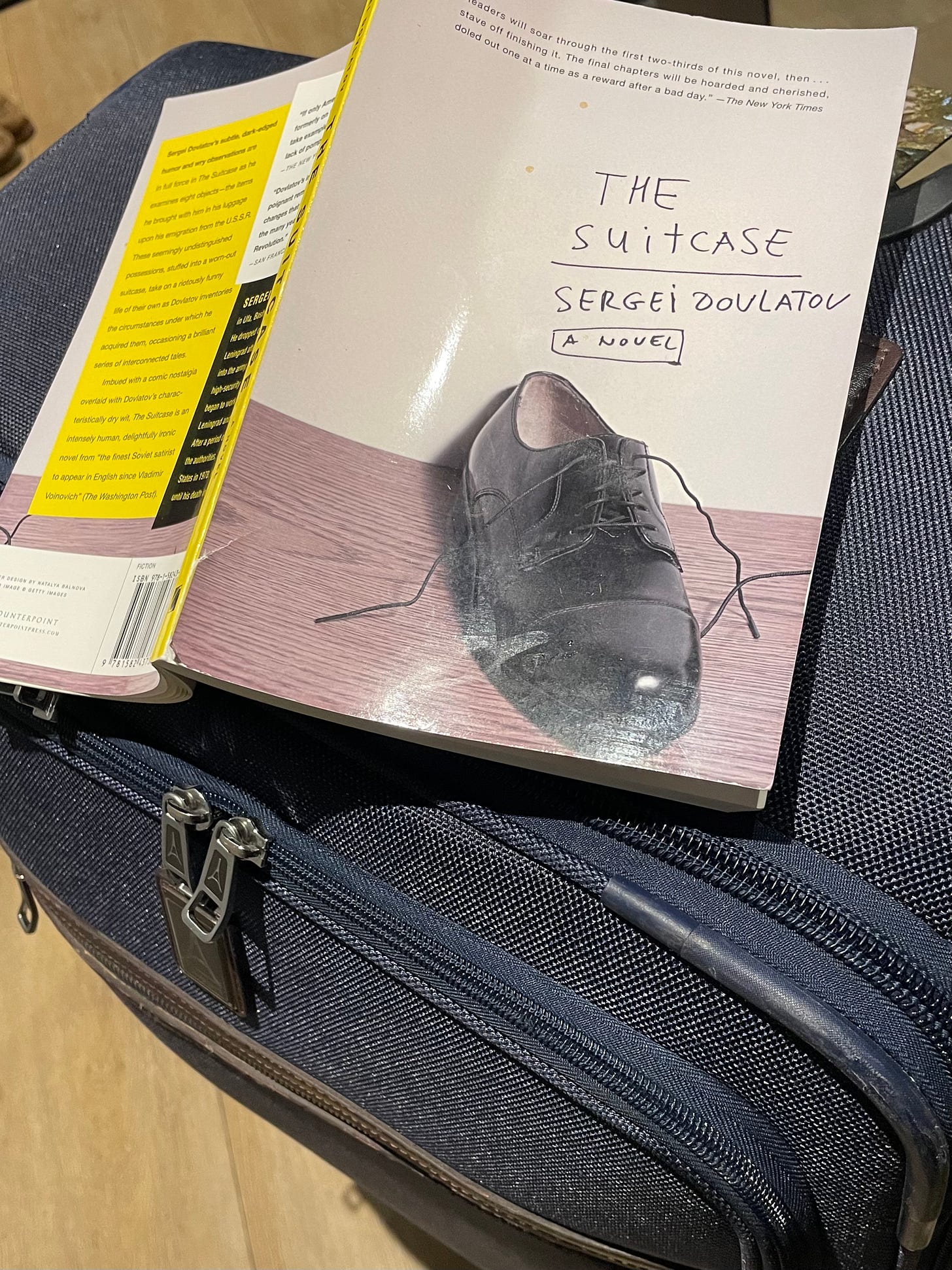

On my outbound flight to Johannesburg, South Africa, I carried Sergei Dovlatov’s The Suitcase into the main cabin. This collection of tales was so entertaining that I didn’t miss the movie screen for a minute. Something else did happen to make this flight unforgettable. About two hours into the journey, when I was several chapters into the book, my husband, who’s always plugged into the news on the ground, received a text: A very dear friend had passed away back in California.

Between that endless flight to South Africa, the shock of an unexpected end of both a life and of a friendship, the unpredictable waves of jet lag and the challenges of making our way around a new place in a new continent, I felt I really didn’t do justice to this week’s unusual book. Reading it through to the end gave me perspective, however, and the afterword written by the author spoke to me about the end of all ends and the very significance of this thing we call a “suitcase.”

The Suitcase is a work in Russian written by Sergei Dovlatov who passed away in 1990. Born in 1941 in Ufa, Bashkiria, Dovlatov began to work in Leningrad as a journalist from 1965. What informs this work is his multifaceted life—his life in the University of Leningrad (he dropped out), his experiences in the army as well as in the high-security prison camps and his life as a journalist in a tumultuous time in the USSR. Translated by Antonina W. Bouis, Dovlatov’s The Suitcase is a look at a collection of objects in a suitcase that the author brought with him as he fled to America from Russia. Every object in the suitcase is allotted its own chapter and each of the objects tells a tale of its own, throwing open a window into the daily life of the former Soviet Union.

Dovlatov examines the eight objects in the suitcase with a wry wit that’s unrelenting from cover to cover. The hideous objects in the suitcase are clearly often useless possessions. Yet they become the stuff of delightful comedy and satire as Dovlatov elaborates on how each of the objects was acquired, making us also wonder if he was ever even right in the head.

The opening story of the Finnish crepe socks was so funny that I almost choked on airplane food which, might I say, was actually edible for a change. Traveling in premium economy made me see life from the other side. Please believe me when I say that, until now, I’ve mostly traveled alongside my suitcase—in the cargo hold. Luxuriating in premium economy as I was, you’ll see why the opening story behind the crepe socks almost killed me.

A con artist he befriended roped in Dovlatov (who was always broke) into his get-rich-overnight black market scheme. He bought hundreds of pairs of Finnish socks (for “a deal”). The idea was to reap their investment many times over by turning around and selling them for a grand profit. Overnight, however, a better version of Soviet crepe socks arrived—in every possible color—in every department store in Leningrad.

And only one thing did not change: for twenty years I paraded around in pea-colored socks. I gave them to all my friends. Wrapped Christmas ornaments in them. Dusted with them. Stuck them into the cracks of window frames. And still the number of those lousy socks barely diminished.

The tale about the stained jacket that once belonged to Fernand Léger, a French painter, sculptor, and filmmaker whom Dovlatov idolized, is so precious, too. We get to meet a young man called Andrei Cherkasov.

In March 1941, Andrei Cherkasov was born. In September of that same year I was born.

Andryusha was the son of an outstanding man. My father stood out only for his thinness.

Nikolai Konstantinovich Cherkasov was a fantastic actor and a deputy to the Supreme Soviet. My father was an ordinary theater director and the son of a bourgeois nationalist.

Cherkasov’s talent thrilled Peter Brook, Fellini and De Sica. My father’s talent elicited even his parents’ doubts.

Cherkasov was known by the whole country as an actor, deputy and fighter for peace. My father was known only by the neighbors as a drinker and neurotic.

Cherkasov had a dacha, a car, an apartment and fame. My father' had asthma.

After this brilliant opening paragraph, how could I not read on? What we learn, by and by, is that his friend Andrei Cherkasov goes on to have a stellar career as a physicist whereas, he, Sergei, only get by as a journalist and a pseudo-dissident poet in a troubled country. What makes this piece one of the most memorable is the connection Dovlatov makes with Andrei’s mother who seems to see him for the things he stands for. When she emigrates to France, she leaves something behind for him, a stained old jacket belonging to Ferdinand Leger. It’s a powerful piece about privilege and the things money can buy. Dovlatov makes us see that Andrei’s mother, despite her sophistication, has seen through the trappings of power, and acknowledged her admiration for Sergei’s values by giving him something of value that only she could afford to buy or receive.

In the recounting of these tales, the author exposes his eccentric self with an intense self-deprecation that’s often both joyful and lovable. My jaw hit the floor again and again.

I thank the late Sergei Dovlatov for entertaining me on what was a difficult week in my life. I’m indeed very grateful for yet another of his lessons, that no matter what may be skewing our lives, it’s important to remember that we’re all here on earth only in transit. The first thing we need to stuff into each of our suitcases is a great sense of humor and an enthusiasm to seize the day whatever its shape may be. In closing, I share an excerpt of the afterword of The Suitcase that I thought was so beautifully executed.

I’ve been living in America for ten years. I have jeans, sneakers, moccasins, camouflage T-shirts from the Banana Republic. Enough clothing.

But the voyage isn’t over. And at the end of my allotted time, I will appear at another gate. And I will have a cheap American suitcase in my hand. And I will hear: “What have you brought with you?”

“Here,” I’ll say. “Take a look.”

And I’ll also say, “There’s a reason that every book, even one that isn’t very serious, is shaped like a suitcase.”

Life doles out loss and gain with a careless hand, doesn't it? When the going gets tough, the tough buy plane tickets. I'm heading for Vienna/the Danube/Instanbul in a couple of weeks, with a copy of Orhan Pamuk's Istanbul on my Kindle. What a travel companion!

I'm sorry for your loss, Kalpana. You said it so well: "The first thing we need to stuff into each of our suitcases is a great sense of humor and an enthusiasm to seize the day whatever its shape may be."