FIRE AND ICE

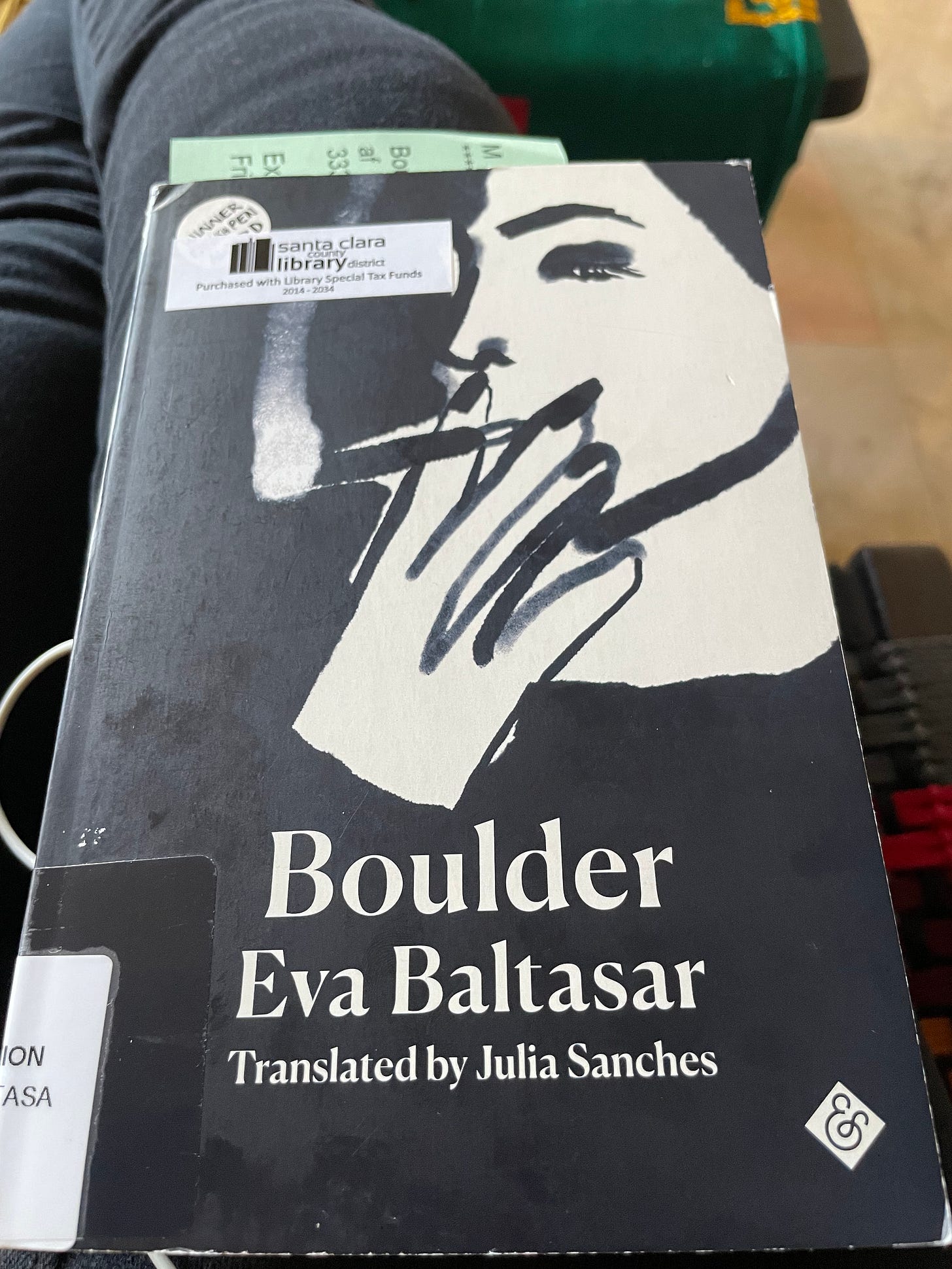

This Catalan novel on the Booker shortlist carves out, with the precision of an Obsidian knife, a story of love and disappointment.

While reading BOULDER I stopped very often to reread a stunning passage. The experience of reading this book was unlike any other and I say this even though I have read some terrific prose over the last year. Eva Baltasar carves with an Obsidian knife and, simultaneously, embroiders with the finest needle. The result is, of course, unforgettable.

Originally written in Catalan and translated by Julia Sanches, BOULDER has been shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023. Baltasar has published ten books of poetry that have earned the 2008 Miquel de Palol, the 2010 Benet Ribas, and the 2015 Gabriel Ferrater, among many others.

BOULDER is a tale about the human capacity for love. What are we willing to give up when we fall in love? If the spirit of give and take nurtures that love, how much is just right to feed that love? Conversely, how much might we take so as to not risk losing that love? Should we let our sense of self be subsumed by our love for another human? The story of how the love of a queer couple congeals from molten lava into shards of ice over the period of a decade is told brilliantly in this supercharged, super short 105-paged novella.

While working on a merchant ship in the best job she has ever had, a cook falls in love with Samsa, a high-flying scientist at an oil company. It’s clear that this cook doesn’t see the need to settle down. Instead, she’s on the move, from one job to another, where she doesn’t form a kinship with anyone even though she’s very good at what she does. Always unfathomable, she says very little about herself to the world even when she must say more at least to save herself.

The cook and Samsa are ignited by a mutual passion from the moment they spot each other across the room. Samsa gives the cook the nickname ‘Boulder’. We understand why almost instinctively. Boulder is inscrutable and unpleasant from the get-go.

“She doesn’t like my name and gives me a new one. She says I’m like those large, solitary rocks in southern Patagonia, pieces of world left over after creation, isolated and exposed to every element. No one knows where they came from.”

What attracts Samsa to her certainly endears her, Boulder, to the reader. Her attitude to life itself is awe-inspiring. Still, no sooner does Samsa meet her than she is already trying to change her. Boulder is clearly too dazed to see this in the first throes of love. The chemistry between Boulder and Samsa ripples with tension—both in and out of bed.

“My kisses are landmines. I set them mindlessly, easy as humming, knowing that when I come back they’ll explode, dismember, unearth bodies and quarries. We exchange numbers. I cling to her the way lunatics embrace new beliefs or dangle from trees. I leave. We’ll see each other in less than three moons. Three moons. Those are the words that leave my mouth.”

Yet the greatest love, we discover soon enough, expects and demands sacrifices. While work on the ship seemed to resonate with something deep inside herself, Boulder recognizes the need to be physically close to Samsa. A woman who has never been able to hold down a job—or a girlfriend—for too long will do anything for love. Several months after Boulder meets Samsa, she follows her to Reykjavik and begins living with her in her tiny apartment in the city. A little over five years into their life together, Boulder meets her nemesis. Samsa declares that she wants a child, “their” child.

Boulder is almost repulsed by the idea of a baby between the two of them. Soon, just as she always does, Samsa sets their goals, expecting Boulder to oblige just as she always has. Boulder does not know how to say no. In a few months, as Samsa grows bigger with the baby, she becomes unrecognizable both physically and mentally.

“The moment she was inseminated, Samsa changed. The feeling I had was one of unfamiliarity—an anxious, nomadic unfamiliarity that came from Samsa. It took over her while at the same time soaking through her and turning her radioactive—as if those mobile vials of life, that freshly brewed soup of despair, had also somehow inoculated her. The birth hasn’t changed a thing; it hasn’t absolved her or brought her back to me. She hasn’t budged an inch: motherhood is that tattoo that defines you, brands life on your arm, the mark that impedes freedom.”

By the time we reach the end of the novel, we know exactly what is about to happen. Boulder, too, has changed irrevocably, however. She has come to love the infant in a way she never imagined possible. She is almost unable to tear herself away from the life she has built with Samsa. The moment is captured in raw undiluted terms.

“I had no idea a child could be such a huge obstacle. Everything around me looks calm, and yet there are no open passages. I am under the thumb of a live, proliferating force that prevents me from leaving and threatens to sever my body, which wants to escape, from my head, which was made to stay.”

Clearly, the baby, lovable as she is, is a choice that was never hers. A successful family life—at least in the way the world continues to define and sell it—calls for the sort of sacrifice that Boulder is unable to offer. It’s why Boulder simply cannot remain anchored to Rejkavik and their home any longer, and why it’s clear to a reader how the narrative must close.

As I turned to the last page, I was reminded of one of the opening scenes of this novel in which Boulder recalls what one boss said to her while showing her the door one day.

“The problem isn’t the food, it’s you.

For me, this line set a menacing tone for the entire story. As the author says, even though the problem isn’t the food Boulder prepares, “kitchens require team effort.”

For Boulder to be perceived as a fit for the world, however, she has to be part of the larger collective mechanism. Unfortunately, her individuality constantly comes in the way. She’ll remain the outsider.

Thank you for bringing this brilliant Catalan novel

👍🏼