FAMILY GOSSIP FROM CAIRO

An expansive Arabic novel about three families in Cairo shows us how politics can upend people's lives, in the very same way, over many generations.

MORNING AND EVENING TALK by the late Naguib Mahfouz (1911—2006) is not the easiest book to navigate, especially if, like me, you are unaware of Egypt’s history over the last couple of centuries. Translated from the Arabic by Christina Phillips, this novel was written in 1987 and is just one in a formidable body of work from this Nobel laureate. The only Egyptian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, the late Mahfouz published 35 novels, some 350 short stories, 26 screenplays, opinion columns for Egyptian newspapers, and seven plays throughout his seventy-year career. His life too has been imperiled by his pen and this story about his stabbing in 1994 will remind readers of the August 2022 attack on writer Salman Rushdie.

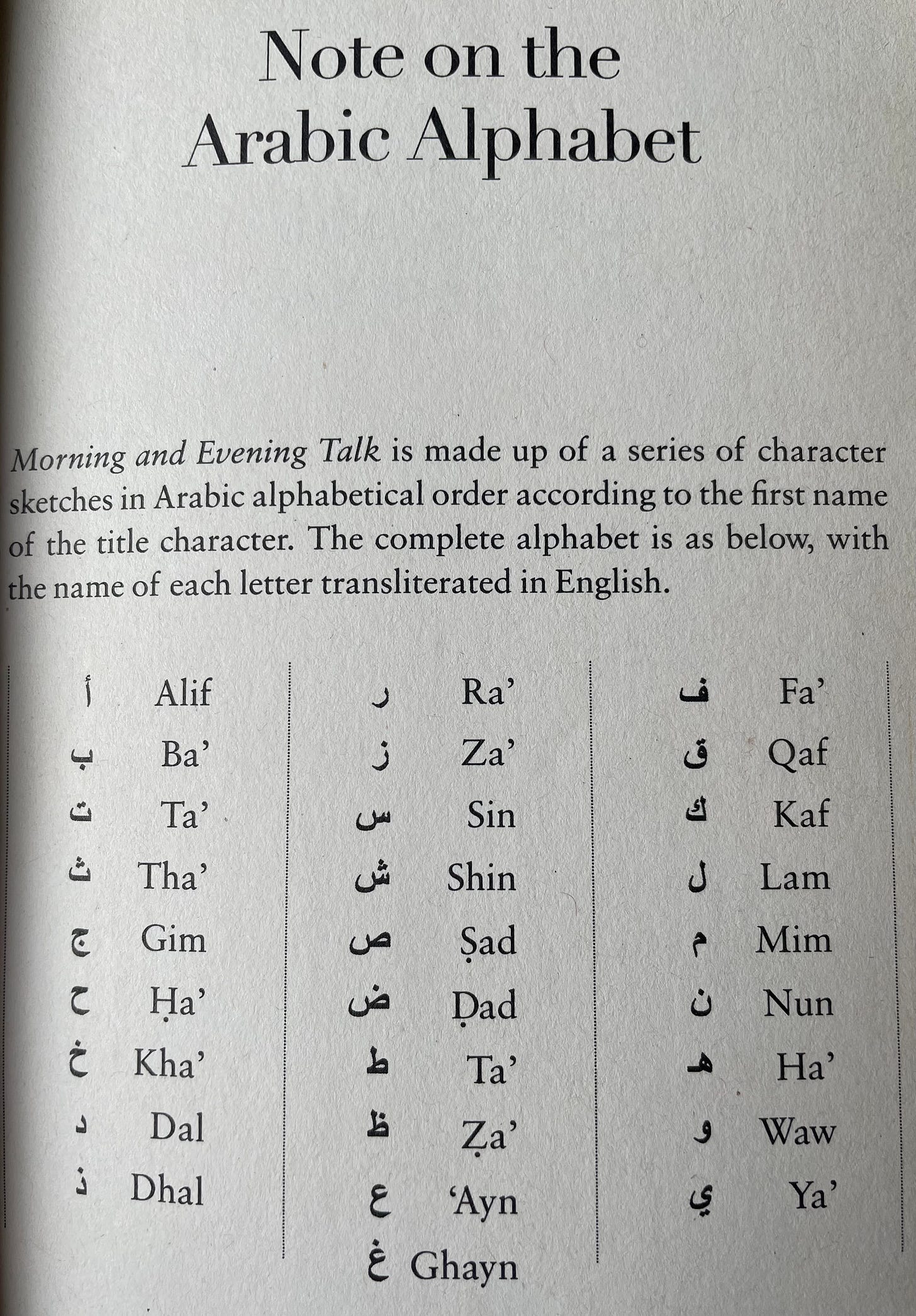

Mahfouz’s approach in MORNING AND EVENING TALK is compelling. Each of his character delineations follows the order in the Arabic alphabet. The author takes us on a journey through different times and attitudes and the personal stories of lives are as varied and tumultuous as Egypt’s own political history following the end of the Ottoman regime.

About thirty pages into the book, I found myself more invested in the stories about the family I met on the very first page. More and more, the extended family members seemed as exasperating and incorrigible as my own.

The people in Mahfouz’s Cairo often married in their teens and went on to have a brood of children. Child mortality was common until the early 20th century , naturally, and we watch several children die young in this novel and we brace for it early on. The opening chapter hints at an impending death. No family is spared this heartbreak.

The three families in Mahfouz’s novel are as loving and helpful as they’re competitive and vindictive. Emotions run high. Many of the men and women are devout and high-strung. While the men oftentimes burst with desire and greed, their women roil in jealousy. The preoccupation with good looks marks every story about every character we meet.

Over and over again, we meet the rotten characters across the generations, the children who, for various reasons, make terrible choices even when they attended school, were smothered by parental affection and enjoyed the love (and judgement) of their relatives who grudgingly tolerated them. As the tides turn, we watch how family members consult one powerful mother figure, Radia, who has inherited spiritual powers from her parents. Time and again, we watch how this blind faith in ancient practices begins to collide with the western mores in a modernizing Egypt.

What we realize as we delve deeper into the novel, however, is how all the inbreeding seems to have dire consequences. The matter of “cousin marriages”, a practice in parts of the eastern world factors heavily in the book. In Egypt, it turns out, at least as stated in this novel, the children of two brothers may—and often expect to—marry. This practice apparently continues even today. As of 2016, about 40% of marriages in Egypt were between cousins. Furthermore, in these “cousin marriages”, a girl is sometimes “reserved by her cousin with money long before puberty”. We watch how Surur, a brother in one of the families, is actually offended that his brother Amr sought his cousin brother’s daughter’s hand in marriage for his son. Amr tells Surur the truth, that wealth and status informed the decision and that sometimes it helped everyone by marrying “up” and forging new family ties.

The custom of consanguinous marriages was common in the olden days to preserve wealth and propagate the tribe. However, it also complicated people’s lives. In the novel, we see how often people’s ethics are compromised by the loyalty they are expected to show to their families. Just as personal interests intervene to sour filial ties, political affiliations create even more turmoil through the generations. Sometimes spouses bury their political ideology in order to save their marriage and buy peace in the home.

In one of the chapters, Mahfouz writes about one talented engineer Hazim Surur Aziz who graduated in 1938 and married Samiha, his wealthy professor’s daughter. His goose was cooked from the day of their betrothal until the day Samiha breathed her last.

“She soon revealed a personality that was impossible to get along with. She was a hurricane that blew up and spread for the feeblest reasons, sometimes no reason whatsoever. He had a constitution that naturally deflected lightning bolts, inherited from his mother, Sitt Zaynab. He lived by his head, not his heart. Thus, seated in the living room, wrapped in navy blue silk robes and submerged in an armchair, he said to himself: So be it. If Samiha had been a perfect bride, or even just average, she would have married someone from the upper class to which she belonged, or a diplomat. Her father had given her to him after much thought and deliberation and he must accept the gift with similar thought and deliberation.”

Hazim “assiduously applauded the revolution in the work place while berating it at home in front of Samiha” because he was afraid of his wife’s wrath and condescension and her potential to make his life miserable. Hazim ultimately went on to head Samiha’s father’s company—he was Samiha’s “proxy” in this too—and we watch a smart, capable man, a big boss at his work, who tended to lose control of his bladder in the presence of his wife, the real boss.

While I found this book useful as an introduction to Egyptian society, I struggled to make all the family connections. The names are too similar, first of all. Mahfouz did not give us a family tree to refer to as we plow through his writing. I also had to do other homework on modern Egyptian history as well. Google was always at the ready. Here are some of my notes from my homework.

1879-1882 The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution was a nationalist uprising

1919 A countrywide revolution took place against the British occupation of Egypt and Sudan in the wake of the British-ordered exile of the revolutionary Egyptian Nationalist leader Saad Zaghlul and other members of the Wafd Party in 1919.

1952 July. A revolution ended the reign of King Farouk. It also triggered the decolonization of Africa.

1956 Tripartite Aggression. Israel, France and the UK forced Egypt in Suez Canal crisis. It began decline of UK.

The word “Infitah” occurs many times in the book (in Arabic it means "openness"). This was Law 43 of 1974 and it relates to Egyptian President Anwar Sadat's policy of "opening the door" to private investment in Egypt in the years following the 1973 October War (also called the Yom Kippur War) with Israel.

The 2011 Egyptian revolution was a statement against increasing police brutality during the last few years of Hosni Mubarak's presidency.

A reader on Amazon summarized her thoughts on this writer with the following comment: “Written when Mahfouz was an old man reflecting on history and the meaning of being Egyptian, this novel can be tedious and sometimes frustrating. The characters' names are often very similar, making it difficult to remember who is who, and the lives of many characters resemble those of other characters and do not add significant new information.” She advises those new to Naguib Mahfouz to start elsewhere for their introduction to his body of work, perhaps “with the more traditional The Cairo Trilogy or even Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth,” written just two years before this novel.

Still, what I found valuable upon picking up MORNING AND EVENING TALK was its personal portraits about the people of Cairo and their thoughts at different points in history. Halfway through the novel, I decided I’d stop worrying about the family tree. Instead of reading it in linear fashion, I began jumping to different points in the text so that I could follow the thread of a character’s life and read about the people who affected their story. In fact, as I did that, I realized this was not unlike a satin stitch in embroidery where the thread goes from point to point until an entire section is colored by the thread and the motif rises clearly to the surface.

In fact, by the time I blazed through to the end of the book, I realized the value of Mahfouz’s exercise. What he was trying to get at—by portraying everyone’s life from beginning to end—was that no one was going to be spared anyway. Like our maker, the author too treated his characters with the same objective pen. I now began to see the larger point being made by Mahfouz, that our angst, our desires, our dreams and our hopes remain the same at any given juncture in time in the story of the world. What mattered then was how each of us chose to live out our days. Few did it well enough in these families. Too many compromised their values and principles. Radia seemed to be the most fully formed of all I encountered. She was feisty, defiant, kind, cutting, thoughtful, generous, jealous, empathetic, proud, candid and intrepid. She loomed large over the course of many generations and many lives.

“She cut through streets swelling with riots and visited the tomb of Sidi Yahya ibn Uqab and invoked eternal damnation upon the English and their queen—for she believed Queen Victoria was still alive.

She never stopped disseminating her superstitions among her children, as well as the branches of the family and neighbors, and became known as the quarter’s Lady of Mysteries. She was known too for her pride in her father’s heroism, owing to which she turned Urabi and his revolution into a legend of miracles and supernatural phenomena, intermeshed with miracles of the Bedouin, Abul Abbas, Abul Sa’d, and al-Sha’rani, and blended with Antara, Diyab, ifrit, magic, charms, amulets, incense and spells.”

She educated her children in her heritage, then when everyone began talking about the nation and Sa’d and the field of consciousness expanded, events became their principal educator. She kept her health and, like her mother, lived beyond a hundred.”

For me, MORNING AND EVENING TALK led to a greater understanding about the personal and political frustrations that ultimately led to the Arab Spring of 2011. After all, the point about reading books in translation is to peer—through the window offered by their words—into a whole new world.

Fascinating and beautifully written, Kalpana.