EIGHT DAYS OF HUMMUS

Shalom! During eight full days in Israel, I began to learn about one community's search for identity even as I tried to process the meaning of hospitality and hostility.

A few days ago, my husband and I returned from an eight-day visit of Israel, a country I’d been wanting to visit for a long time. There is something to be said for not planning a vacation too far in advance. Some of our best trips have happened at short notice. Late in August, we felt that there was a window of opportunity when the Holy Land seemed relatively at peace, when winter was still some months away and when my birthday, too, was right around the corner.

Besides visions of the softest pita and the lightest hummus, what really drew me to Israel was the multi-layered history of a tiny land. Israel is 85 miles at its widest point and just 290 miles from north to south. The country was carved out for the Jewish people after the second world war, and in, literally, eighty years, the people have built something fantastic for themselves in every sphere of life, including the sciences, arts, and technology.

It turns out that Israel also leads the world in desert agriculture. Eighty percent of the produce consumed in the country is homegrown even though the nation has only twenty percent of naturally arable land. I learnt that the Negev Desert has actually shrunk in size over the past century as agricultural activity has turned sand into green fields. Of course, Silicon Valley residents like me have known that Israel is startup haven, too; my husband reminded me that some of the apps I’ve been familiar with were Israeli innovations: Waze, Moovit, and Gett, to name a few.

In the city of Tel Aviv (which felt like a mini New York), we stayed at Hotel Saul, a boutique hotel with a café loved by the locals. Gili’s Coffee House was buzzing from morning to night and a local couple told us we could not have chosen a more happening place. Breakfast was so scrumptious and filling that we weren’t hungry until dinner. At Gili’s I learned that a Jerusalem bagel is quite different from the New York bagel, now the gold standard for a bagel in America. Typically, the Jerusalem bagel is a yeasted, crusty bread which is shaped into an oblong ring and covered in sesame seeds. The dough has a lighter texture than a traditional bagel.

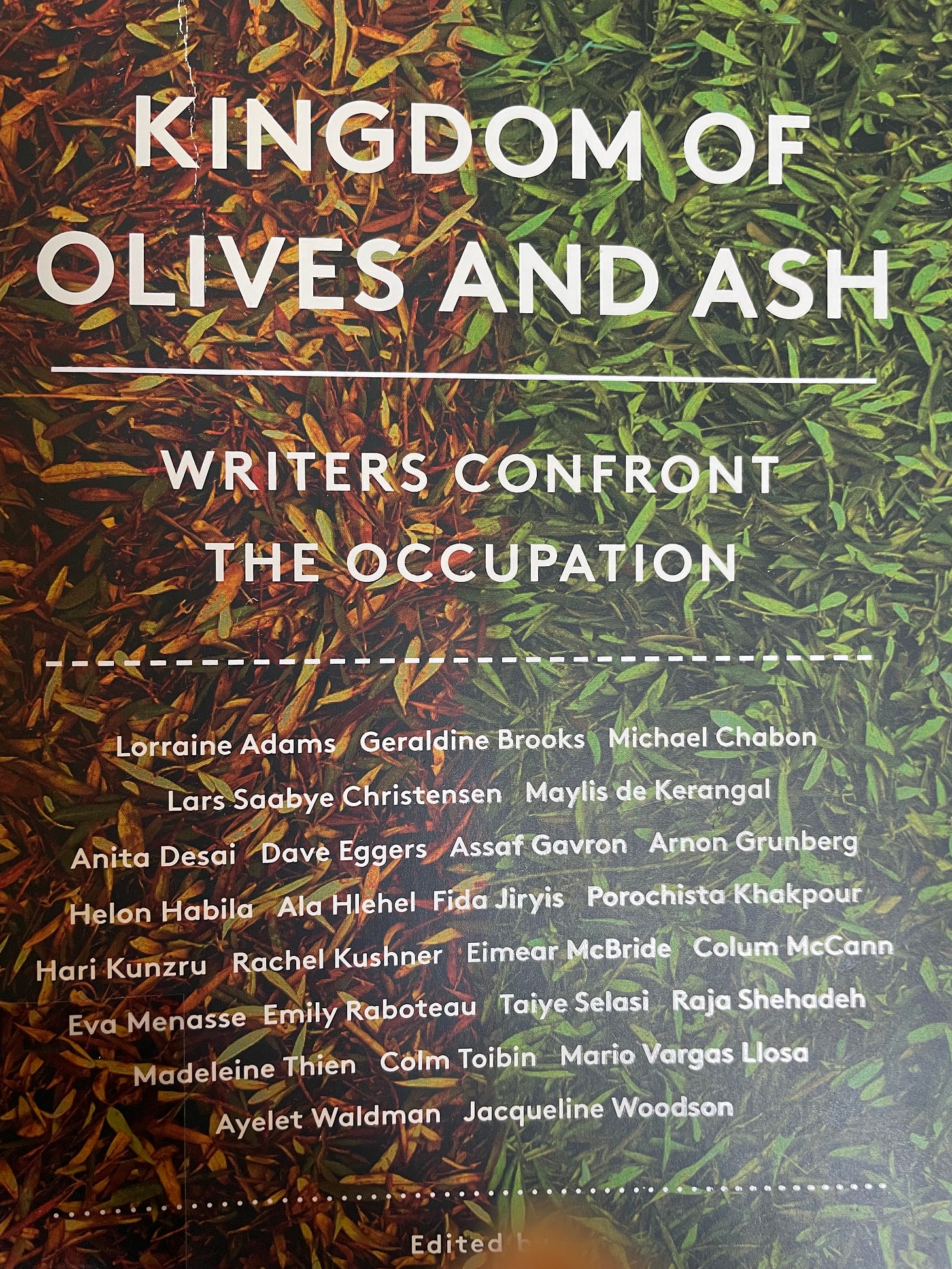

While hanging out in Tel Aviv on the first two days of our stay at Israel we could not imagine that there was another world not too far away where life was radically different. Writers Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon sum it up thus in a book they edited titled Kingdom of Olives and Ash: “The city sparkles; it hums. And it averts its gaze. One would never know, on the streets of Tel Aviv, that an hour’s drive away, millions of people are living and dying under oppressive military rule.”

On this parcel of land, living, dying, oppression, and persecution has continued unabated for centuries. Are some places always destined to be thus, just as some families are dysfunctional, yet functional, from generation to generation? This other world, however, was not obvious to us in the Tel Aviv we saw even though old, forgotten Jaffa, one of the oldest known ports in the world, hinted at the possibilities of a different world.

The promenade by the beach at the eastern end of Jaffa is grand. So too is the view of women in thongs soaking up the sun—or attempting to do a headstand—while just a few feet away in the foam of the Mediterranean, Muslim women in hijab frolic about with their children. In contrast, the deeper we walked into the old city of Jaffa, the more otherworldly it felt, with the press of poorer neighborhoods and small Arab establishments. Time seems to have stopped in this old place. Beyond the main drag, the alleyways are so narrow two bicycles may not pass each other . The faint smell of a falafel ball frying never seems far away.

I found Israel to be a happy place where there was a little too much eating and drinking and holidaying. The thing that got in the way of our needs was the Israeli need to close businesses early on Fridays and Saturdays. The day of our return to the United States, everything closed early since it was a Friday. We decided that renting a car again was our best option if we wanted to see two other museums in Tel Aviv before catching our flight back home.

The best part of renting a car in this country was the promise of satin-smooth roads and clear signage in Hebrew, English and Arabic. What was never a guarantee, unfortunately, was the temperament of the drivers themselves. My husband—who is very impatient—found Israeli drivers to be terribly impatient. Before we flew to Israel, our friend Alon wished us luck, warning us that renting a car and contending with Israelis on the road may be unpleasant. We informed him that those of us who had driven in India tended to be unfazed by drivers in any part of the world.

Despite some discourtesy on the roads, we found plenty of kindness in the country. Before the trip and during our stay in Israel, we were in touch with several friends who helped us figure out our itinerary. In Haifa, a power couple, Rita and Freddy Bruckstein, both professors at Technion, treated us to a fabulous spread at a rooftop restaurant. We finished our meal with the syrupy knafeh recommended highly by a friend. It was so light on the tongue that I forgot it would weigh heavily on the scale when I returned home to California. There were many other sweet moments.

En route from our trip to the Dead Sea, we crawled past a roadside vendor who handed us the sweetest, plumpest dates to taste. When we gave him a dollar (we didn’t have two shekels), he was mortified. He wouldn’t accept it until we had at least tasted his tea in exchange. On another morning at a parking lot in Jerusalem, the lot owner pocketed the 20 shekels and waved us off when we didn’t have more change to cover the entire parking fee. For four days, Razan, the gorgeous receptionist at Jerusalem’s Hotel Bezalel, took care of us as if we were family.

I’ve always been overwhelmed by Middle-eastern hospitality. Years ago we were in Turkey’s Izmir where the fare at breakfast, lunch and dinner were sumptuous. I’d experienced the same in San Jose’s Almaden Valley at the residence of our Iranian friend whose dinners were always lavish and decadent.

At Hotel Bezalel, we were treated to wine, snacks and dinner every evening. I wondered how this hospitality might play out in the really opulent hotels in these parts such as old Jaffa’s The Setai situated on the Mediterranean, its palatial precincts sculpted out of a prison from the former Ottoman period. Hospitality in this part of the world is about fanfare and ostentation. Everything has to be big and fat. Imagine a tray of baklava dunked in a pail of honey. I believe, however, that the warmth, the overfeeding, and the cloying sweetness of the people in these parts often belies their tendency for aggression.

In a land that has erupted in violence and anarchy many times over—under the Romans, the Persians, the Crusaders, the Ottomans and the British—memories and mistrust probably run deep. The history of the Jewish people is one of survival, against the greatest odds, century after century, over many thousands of years. I quote Winston Churchill (who, incidentally, had nothing kind to say about black or brown people) on the nature of Jewish resilience: “Some people like the Jews, and some do not. But no thoughtful man can doubt the fact that they are, beyond all question, the most formidable and the most remarkable race which has ever appeared in the world.”

In Israel I saw evidence of a people working extremely hard to preserve their culture. I saw this not just in the strict observance of their holidays. I saw it in how every adult and child adhered to the dress code in the Old City. I also saw proof of this tenacity in their nurturing of Hebrew, a language that, for all practical purposes, had been dead for centuries. How did Hebrew blossom into a living language over the last hundred years? A language without any native speakers subsequently became a first language to several million people. For Indians like me who did not have the privilege of learning deeply their mother tongue (although I do read and write in Tamil), this is a lesson in how preserving language is one of the ways to stem cultural erosion.

Israel is hardly homogenous. Most places in the world are a mingle-mangle of people. Just as there are Jewish Israelis whose ancestors arrived here from many parts of the world, this country is also teeming with Arab Israelis. Some 7 million people were Jewish people of all backgrounds, about 2 million were Arab of any religion other than Jewish, while the remaining half a million were defined as "others".

While hanging out in Tel Aviv on the first two days of our stay at Israel we could not imagine that there was another world not too far away where life was radically different. Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon sum it up thus in a book they edited titled Kingdom of Olives and Ash: “The city sparkles; it hums. And it averts its gaze. One would never know, on the streets of Tel Aviv, that an hour’s drive away, millions of people are living and dying under oppressive military rule.”

Just about every conqueror managed to leave his stamp on this land. In the ruins of Caesarea (halfway between Tel Aviv and Haifa) built by King Herod in the 1st century BC, we saw a typical Roman city with a lookout into a magnificent harbor. In 10 BC, the harbor was the most sophisticated man-made harbor of its time, covering sixty acres with mile long piers. It could accommodate hundreds of vessels of different sizes and its piers were served by an enormous system of warehouses. A few days later, we also went up a cable car to see King Herod’s fortifications at Masada overlooking the Dead Sea—a rugged natural fortress on which the emperor constructed a sumptuous palace complex in classical Roman style.

For me, a personal highlight was stopping at the churches dotting the Sea of Galilee, each of which is a pilgrimage site in Christianity. On a stop at the first church where I dipped my feet into the Sea of Galilee, an Indian woman on a tour bus with pilgrims from Kerala wondered if I were a Hindu who had converted to the Christian faith. “No, I’m a Hindu,” I said, “but always interested in seeing all the places holy to Christians.” I told her that in Galilee I actually felt as if I were back in India’s Benares. The most sacred places in the world, energized as they are by the light of realized souls, seem to meld and merge.

Rita Bruckstein had warned me that the churches along the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee were small and inconspicuous and that I should not travel to Galilee expecting grandeur. I suppose this was precisely why I found these places so sacrosanct and peaceful. They were invested with the wisdom of the centuries. Some of these were sacred ground where Jesus is believed to have preached; at some others, he was believed to have performed miracles.

At the Church of the Multiplication, a Roman Catholic church located at Tabgha, we saw restored 5th-century mosaics. These are the earliest known examples of figurative floor mosaics in Christian art in Israel. Aside from wetland birds and plants, the mosaics give prominent place to the lotus flower, popular in Roman and Early Byzantine art. The mosaic found in front of the altar depicts two fish flanking a basket containing four loaves of bread, one of the seven miracles attributed to Jesus Christ. Further north, in the ruins of Capernaum, we were at the site of the synagogue where Jesus is believed to have healed a dying man.

Personally, I found these sites more inspiring than Jerusalem’s magnificent Temple of the Mount. Part of the problem in all the holy places in the world is the swarming security that stands around toting guns, reminding us that it’s impossible to ever separate church from state. While the sight of the Western Wall and the Dome of the Rock was magnificent both from a distance and up close, I was frustrated at being hurried and herded along, especially at the Al Aqsa Mosque where I was also expected to don a thick ugly skirt and an equally frightful hooded top simply in order to walk on those hallowed grounds.

One of the unforgettable highlights of this trip was our six-hour walk through the quarters of the Old City of Jerusalem during which we experienced the sights and sounds of the Armenian, Jewish, Muslim and Christian quarters and also traced the winding route of Jesus Christ on the way to his crucifixion on Via Dolorosa. In these hallowed grounds, the paths of three religions had crossed, making them, literally, indistinguishable from the other even though man had succeeded in splicing them apart. One day is hardly enough to do justice to the layers of the Old City; we never found the time, for instance, to go on the Ramparts walk, one of the most unique Jerusalem walks across the walls of the Old City.

On our visit to Bethlehem, a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about six miles south of Jerusalem, we were waved through at the green line while returning to Israel. It’s hard to not be intimidated by the tall fencing with wires above them, the walls stretching over the tunnel leading into Palestine. Our trip was uneventful, after all, and it was clear that this was a standard tourist circuit. What struck me was the stark difference between Israel and Palestine in the short drive to Bethlehem. The villages we passed looked derelict and unkempt but what grabbed my attention was the number of beauty salons in our short ride through Palestine. People were wanting to look good. What could be better than that? Didn’t this point towards hope?

According to our guide George, ten years ago, thirty percent of the town of Bethlehem was Christian; today the number is at one percent, thanks to a steady exodus of people from both communities. I’d have liked to ask George how he had chosen to become a guide in what seemed to me to be a holy place that, ironically, also had a godforsaken quality to it. I’ve not finished reading my copy of Kingdom of Olives and Ash but reading the essays makes me terribly sad for all that has been lost. During our few hours in Bethlehem in West Bank, George observed that none of the daunting fences between Israel and Palestine would resolve anything in the long run. “The only sure way is by building bridges,” he said. “We must do it with love.” All the tourists in the van nodded in agreement although I suspect that none of us knew exactly how we might go about it.

As I flew back from the Holy Land to the United States, I realized that of all the things we must cherish during our brief time on earth, the most important was a sense of identity; the second most important thing, as my late father might have put it, was to own a small piece of land that we could call our own. It’s what the people of Israel seem to have fought for throughout the centuries; it’s what each of us is always fighting for every day. In the course of searching for our identity and staking our claim to our piece of land, we often forget that our neighbors, too, have a desire for exactly the same things.

You traveled with belly and mind and heart engaged. And now I have too. Sweet and sad. Have you ever read any of the Traveler’s Tales book series? They’re collected essays and anecdotes from specific places around the world. We’re traveling in France right now accompanied by two of them (TT France, TT Paris). It’s great to read your way through and into a landscape.

What a remarkable trip for you and Mohan! Reading your excellent trip report made me transport to Israel in my "inward eye" as if navigating the immersive Metaverse full of culinary and cultural experiences ;-) Keep on writing Kalpana ji ..its uplifting