DEAR GOD, ARE YOU THERE?

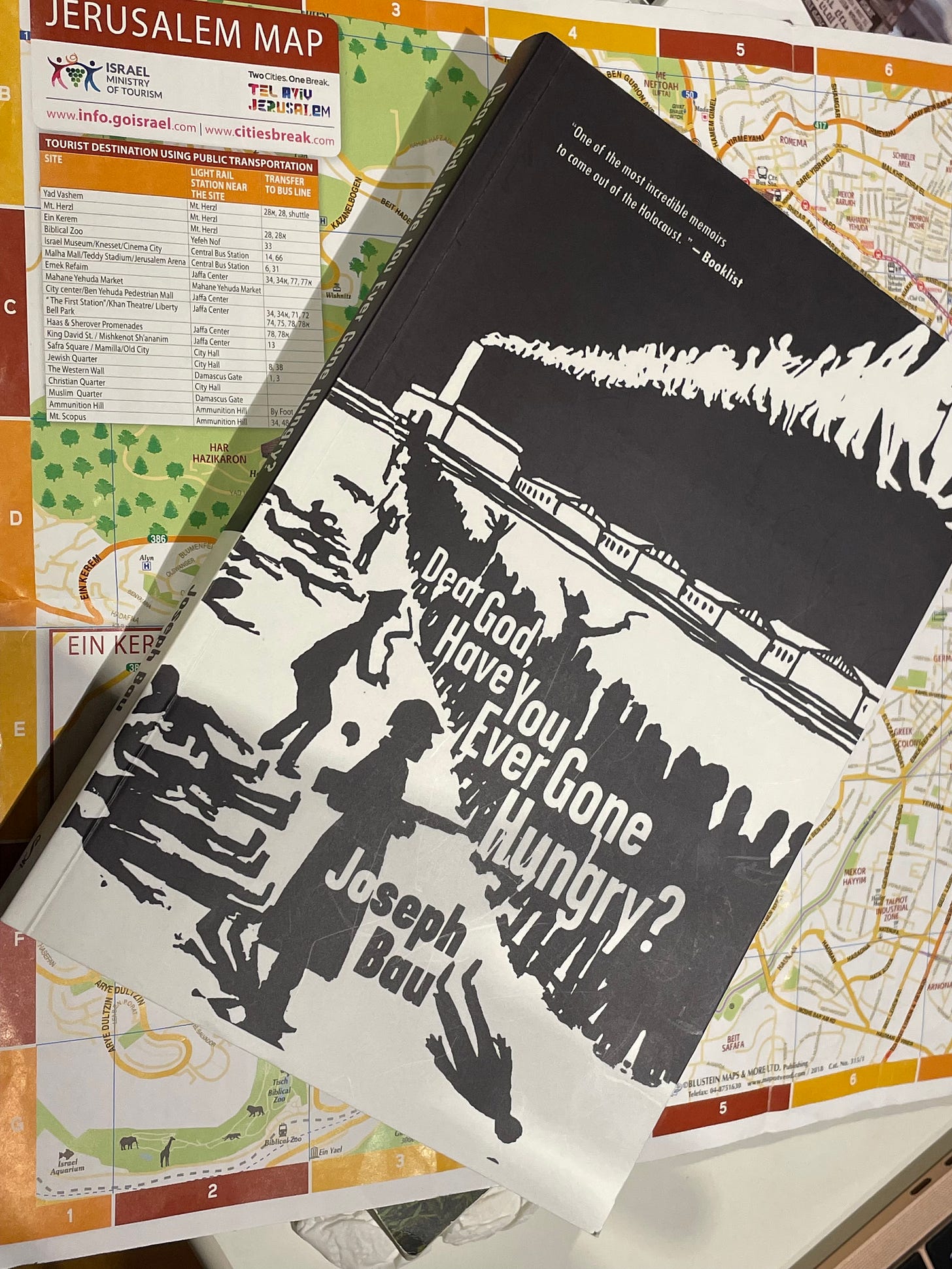

I bought Joseph Bau's memoir in Tel Aviv and read his poignant story a few pages at a time. How else do you read the story about a family at a concentration camp during the second world war?

It seems that books tend to arrive into my life at unexpected times and in the most memorable ways. On our recent trip to Israel, we were not exactly expected to return to Tel Aviv on the last day. Our plans changed, however, when we discovered that there were no frequent trains from Jerusalem to Ben Gurion Airport in the evening before we were to catch our flight.

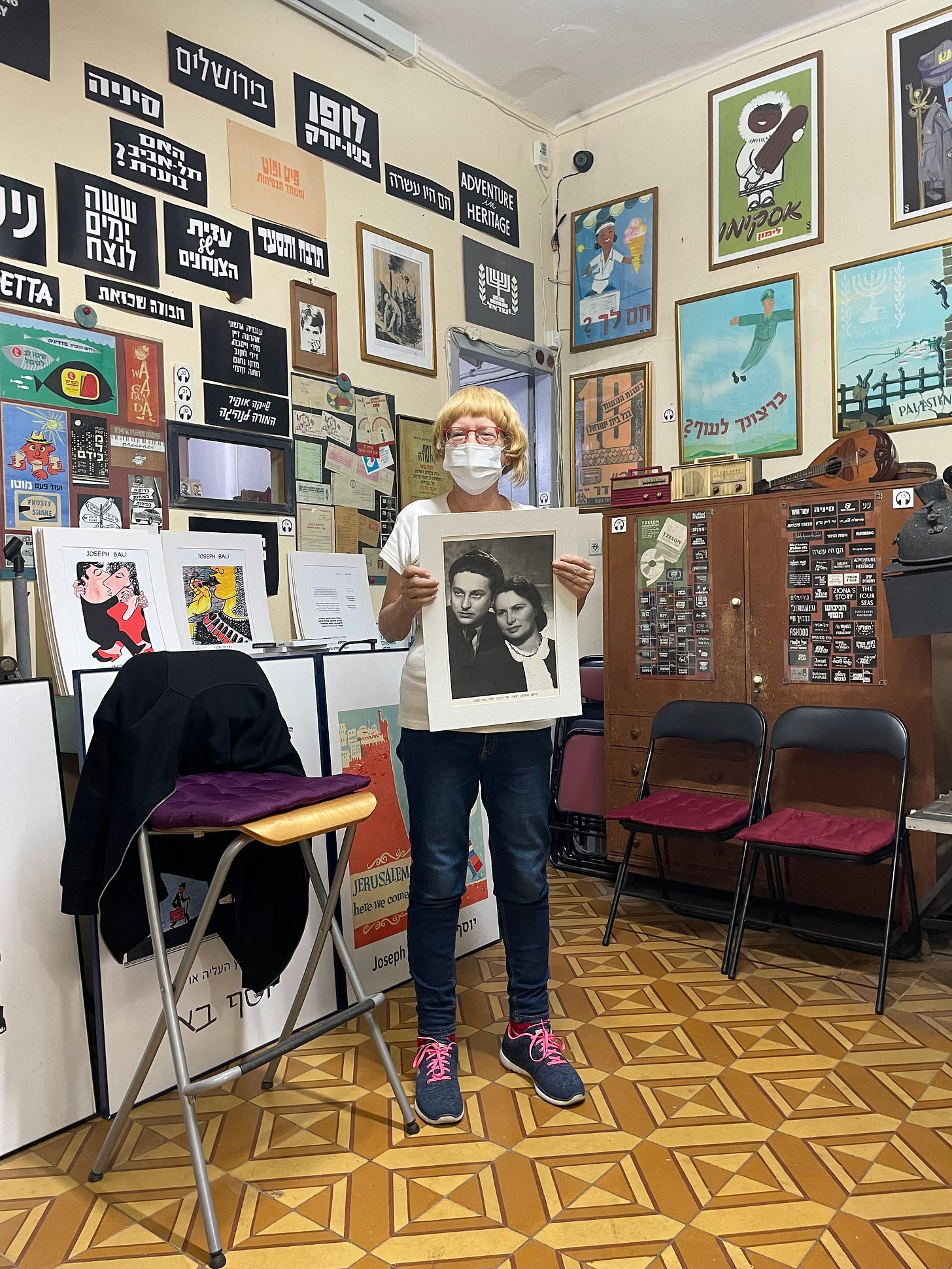

We ended up driving to Tel Aviv in the morning to spend a whole day in the city. We spent time at the Joseph Bau workshop and museum a few hours before we boarded our flight.

The building houses the studio where the late graphic artist, Joseph Bau, worked for many decades. Today, his daughters, Hadasa and Clila, have turned it into a museum showcasing his art, his publications, his animated movies and the original equipment he built to create his movies.

I’ve just learned that a few days ago Bau’s daughters found out that the building which houses the museum will be torn down in two years. It’s unclear what will happen to this piece of history. Bau’s daughters expressed their anguish as part of their presentation lamenting that they didn’t have the money to move the exhibit to a new place. Furthermore, they don’t want to leave the place where their father built a life and found success. I could see why.

Bau’s old workshop is housed in a building in Tel Aviv’s historic district, barely ten minutes by walk from Bialik Square renovated in 2009, a popular place that is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. This is Tel Aviv’s museum district. This authentic workshop from the past needs to be on every Tel Aviv visitor’s tourist itinerary because it tells such a compelling story of a survivor. According to the Bau daughters, it’s the only museum of its kind in Israel, and in the world, that combines the holocaust, the love for Israel and the passion for the Hebrew language.

The book I bought at this Bau’s workshop—Dear God, Have You Ever Gone Hungry—is a memoir in Hebrew written and illustrated by the late Bau. Translated by Shlomo “Sam” Yurman for what is such a smooth read, this is the story of how one man—and the woman he married inside Krakow’s Plashow concentration camp—managed to save countless people from death under German hands.

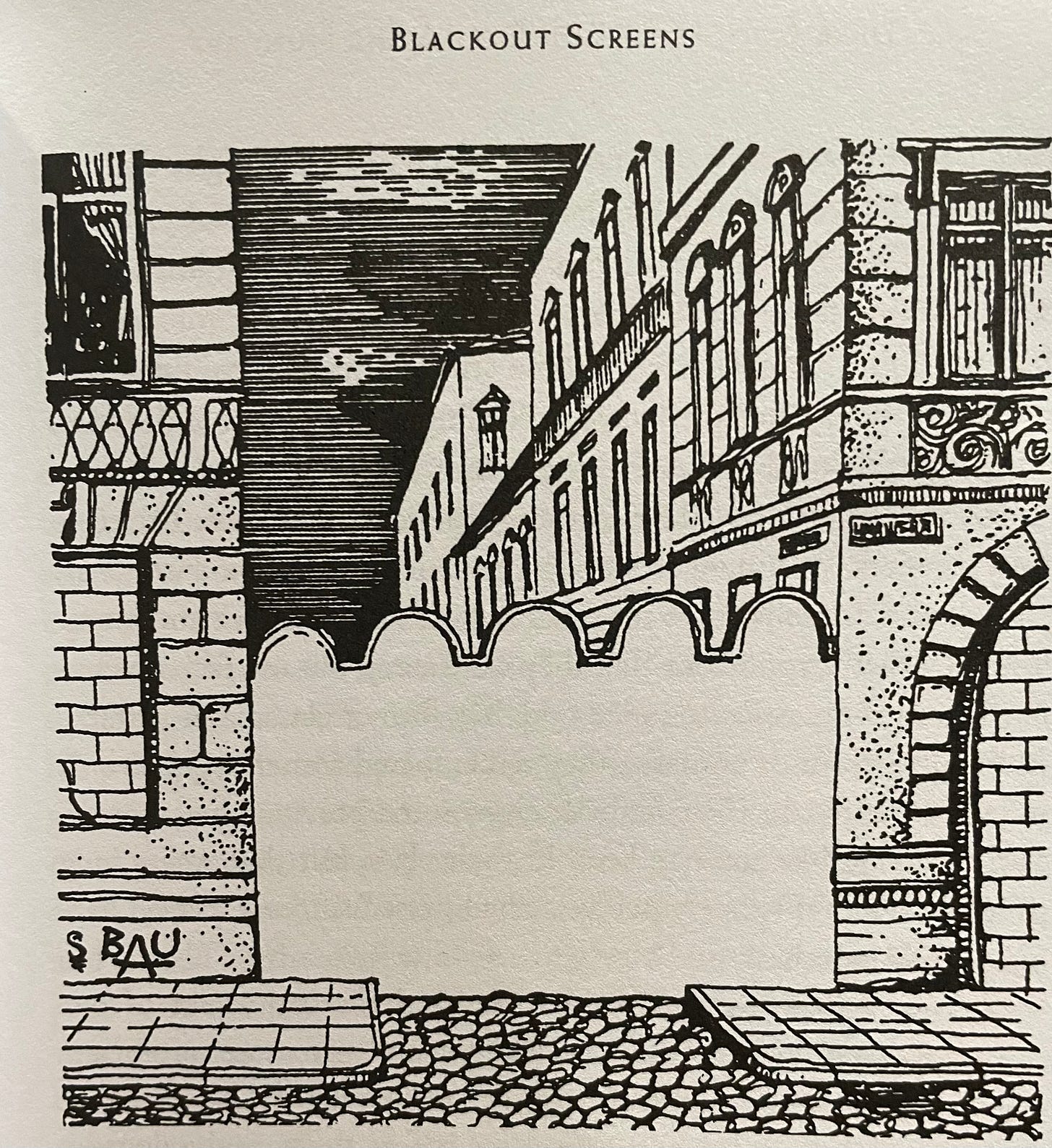

Bau leads us into the ghetto in Krakow at No. 1 Plac Zgody—”Peace Square” in Polish. “What an irony!” he writes. He observes that the Germans had been inspired by the Middle Ages from which they not only lifted the term “ghetto but also built their tall fortified wall following the precepts of the olden days.

“A formidable stronghold, with walls built of bricks held together by hatred, the ghetto was designed to hold a population of Jews in unbelievably crowded condition. Every room was occupied by several families, each of them with a few pieces of furniture and an assortment of worries and problems. One kitchen served all these families so its use had to be scheduled by the hour. A line of impatient people, some unable to contain themselves, always waited outside the toilet.”

Almost right away in the memoir, Joseph Bau’s greatest quality rises out of the pages. He was a fount of optimism and grit, the kind that makes some people transcend dire hardships. Bullets whizzed past his ear on several occasions and he still lived. While luck certainly played a part in keeping him alive, it’s clear that Bau’s quick thinking and pragmatism saved his skin on many occasions. What was expected to be a dark work like Night, Elie Wiesel's masterpiece about the holocaust, is, instead, a straightforward account with some wondrous laugh-out-loud moments. The things that happened to Bau would have made me weep and not stir out of bed for days. Yet, there he was, getting up again, picking up the remaining pieces of his life to go on and face another day even when he was overworked, abused and hungry.

Reading Dear God, Have You Ever Gone Hungry? is gut-wrenching from the perspective of hunger. Of all the great sorrows in the world, surely the most harrowing must be to go hungry for days on end. Bau writes about that, too, in his particular tone, squeezing out a laugh along with a tear. The poor lighting or the lack of it in the alleys and in the tenements added to the misery of perennial hunger inside the ghetto.

On one of those days when Bau’s family was looking forward to a great meal after having come into a little more money, Bau drops a whole pot of bad beet soup at the door step of his home. Dirty dish water falls all over the food his mother brings home. As luck would have it, Bau’s brother Marcel who was making potato pancakes manages to ruin them too. Bau’s words for the happenings of that appalling night recall the nightmare in gory detail. The family went to bed even hungrier that night.

The pancakes were ruined. They had been such a success that Marcel had decided to increase the quantity by adding more water and flour. Working in the dark, he picked up a bag similar to the one holding the flour and poured its contents—soap powder—into the pancake batter. In the resulting chaos, the first batch of pancakes, which had been soap-free, were burned to charcoal.

Bau, however, was hopeful all along. Even in the depths of the holocaust in the midst of a concentration camp, he found reason for hope. Clila Bau told us how in his darkest time, there was one human being who certainly lent meaning to his sordid life.

During their internment in Płaszów, Joseph Bau and Rebecca Tannenbaum met and fell in love. Their clandestine wedding—depicted in the Steven Spielberg movie Schindler’s List—took place on February 13, 1944. The life-long love that began during the horrors of the concentration camp lasted almost five decades, until Rebecca’s death in 1997.

After that, however, a man who had been so optimistic through the greatest of ordeals, seemed to lose his purpose to live. His daughters described how their unflagging, energetic father, seemed lost and adrift upon their mother’s death. It reminded me so much of my own father’s predicament. The year of the Bau marriage was reminiscent of events in our family, too. My own parents were married a few months after the Bau couple, in May 1944, and their wedding was celebrated with much feasting over a four-day period in India’s Kerala.

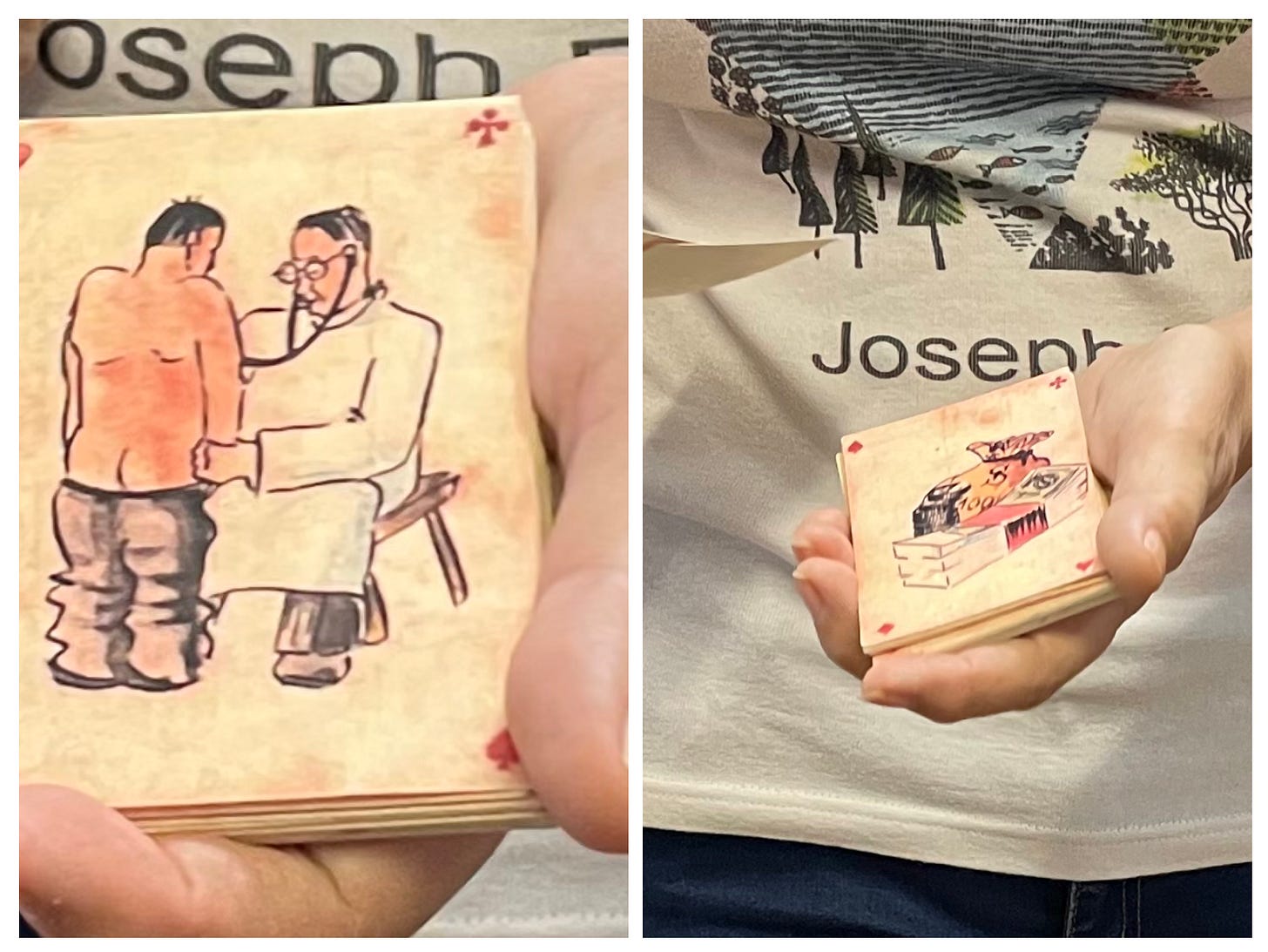

Years after his death, his family learned that Joseph Bau had worked in the Mossad as a graphic artist who forged documents for Israeli spies, including Eli Cohen. Joseph Bau immigrated to Israel in 1950 with a dream to make animated movies in the Holy Land. He made a mark in the advertising industry and gave form and shape to Hebrew fonts, too, it turns out. This was a man with tremendous spirit and verve, with an aliveness that was obviously infectious. He would put it to use even in the worst of times. The daughters talked about the ways in which Bau tried to talk his fellow inmates into not killing themselves. Suicides were all too common in the concentration camp. When Joseph Bau saw the flagging will to live, he looked for ways to change people’s minds.

He managed to create a hand-drawn set of playing cards while at the camp. When people were dejected, he showed them cards and narrated possibilities that would put a smile on their lips and light up their eyes. “Why do you want to kill yourself? One day you may find the love of your life. One day you may have a baby. Look at all the things you must live for. Just think, one day you may need to be seen by a doctor. One day a thief may rob you. Or one day, you’ll come into money.” Of all the things Clila Bau said to us that evening, these words moved me the most. To convince people that they must live on just because. What spirit must it take for one human, who is himself not in the best shape or situation, to persuade others to not give up their will to live?

I close with one page that describes one of the ultimate tests Bau is forced to endure. On page 202 of his riveting memoir, Joseph Bau describes how he happened to watch his father being put to death. “As my father walked toward his death, his stooped back obscured the view. I didn’t feel the broken road under my feet, or the sharp stones, nor did I see the people looking on with compassion. I wasn’t even aware that I was waving the egg-stained newspaper over my head. My cries became an inhuman hoarse bellow. I was getting closer, but suddenly someone pulled me aside, held my head, and embraced my neck with his arms, while hugging me close.” The man who forced Bau to go on living that day was his friend Isaac Stern. He told Bau that he needed to live so he may avenge his father’s death.

You’re a brave reader. Thanks for reporting from the abyss.

Love the poignant narrative Kalpana. Such Bravery and the Will to live when confronted with inhumane depths of despair is rare. Therein God shows His presence in people like Bau! Willing others to live and look forward to another day.